Whales are central to an understanding of the Pacific, and Aotearoa New Zealand is no exception. Take the pūrākau of Paikea, a common ancestor of east coast iwi of both islands. It’s a whale’s tale if ever there was one.

There are various versions of Paikea’s journey across the Pacific to reach these shores. However, they pretty much all involve whales playing a central role in his rescue from a marine disaster.

As retold in a chapter of Across Species and Cultures: Whales, Humans and Pacific Worlds, which is being launched today in Dunedin, Paikea is carried on the back of a whale or, in another version, turned into a whale, a tohorā.

In memory, the storied voyager becomes "he tahito, he tipua, he taniwha, he tohorā, he tangata, he tekoteko". An ancient being, an extraordinary being, a denizen of the deep, a whale, a man, a sentinel for his people.

Whale and man are inseparable.

As for Paikea, so for so much of the Pacific Ocean and its peoples.

Yet Across Species and Cultures is the first attempt to seriously examine whales’ place in the history of the Pacific, to allow their epic, hardly fathomable voyaging to bind the ocean’s stories together.

Edited by Prof Angela Wanhalla, of the University of Otago’s department of history, and Prof Ryan Tucker Jones, who teaches history in Portland at the University of Oregon, the book spreads out across the big blue, its 13 chapters — each contributed by a different author — investigating the intersections between whales and people across the centuries.

"It is worth exploring whales as the heart of that story rather than thinking about it from the perspective of the people," Prof Wahalla (Kāi Tahu) says. "Placing whales at the centre gives us a slightly different approach to thinking about the Pacific as an ocean with animals in it, who have been impacted by the arrival of human cultures and societies."

When they are at the centre of the story, we see shared connections across the Pacific — and differences too, she says.

"For me in particular, whales help us connect the indigenous world with traditions about the ocean and its animals."

Prof Jones is at the pointy end of whale-human connections. His area of particular interest is whaling, specifically Soviet whaling. The epic slaughter that the Pacific witnessed has been super important for Pacific history, the environmental historian says, "the history of the ocean, the history of the countries that border on the ocean — New Zealand, Australia, the US — whaling has been really central to all of our histories — Japan as well".

But even here, as with Paikea, the whale is not the passive object of human activity.

Even in modern times, what emerges is the role whales themselves have played in these stories, as characters in their own right. Marine biologists have been critical to that growing understanding, Prof Jones says, revealing more of the creatures’ own lives.

"We can really imagine, we can retell these histories in a new way because we have new insights into the whales’ side of the story, as it were."

What we are into here is whale culture.

"What biologists have been able to show ... is that whale behaviour is not just shaped by evolution, natural selection. Whales, some species at least, they’re sophisticated communicators, they have tight social bonds, they travel over vast distances looking for food, and all of these factors encourage the development of culture. Which, as I understand it, is defined by most evolutionary biologists as the transfer of information through the generations — not through the genes but through some kind of social learning."

It is exciting, Prof Jones says, because it means whales have history in a similar way to humans.

In human history, cultures change as a result of impacts on them or as a result of human choices, and that’s true for whales as well.

"So, it makes sense for us to rethink our relationship with whales when we realise that, say, a sperm whale from Moby Dick in the 1840s is a very different sperm whale than is out in the ocean today that people might be looking at off the coast of Kaikoura."

We’ve changed, the oceans have changed and whales too, he says.

"They help control this history, they have helped write this history."

In a chapter written from the bowhead whale’s perspective, penned by Brown University assistant professor Bathsheba Demuth, she describes how the Bering Strait whales reacted to the onslaught of whaling by radically changing their behaviour, employing new tactics to elude the hunt. Numbers killed plummeted from more than 2000 in 1850 to 900 in 1851, as whales ducked for cover under the ice.

"After three summers of observing mass death, the value of the ice had changed for a bowhead: the whales began using the floes as a tool against slaughter. Their culture, at the surface observed by commercial hunters, became one of choosing not to die for the market," Demuth writes.

Interestingly, the indigenous peoples of the area experienced no change in behaviour when it came to their traditional hunting using walrus-hide boats.

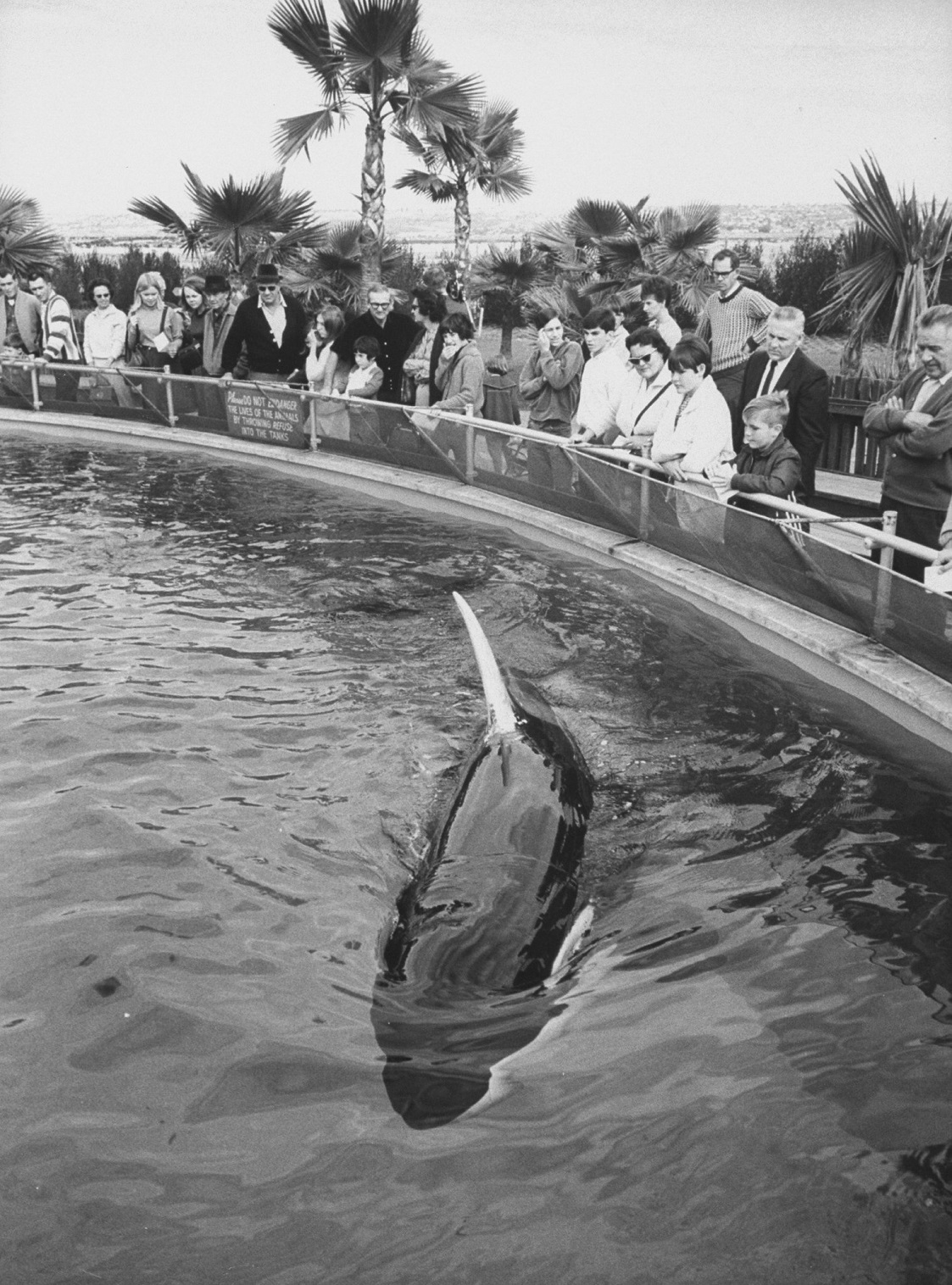

The phenomenon of changing whale culture is explored further in a chapter by Prof Jason Colby, focusing on Gigi, a grey whale that became a Sea World marine circus celebrity in San Diego in the 1970s and may have gone on to completely recast the relationship between its species and humans.

Grey whales were the object of some of the bloodiest and most frenzied episodes of US whaling, pursued to their secluded lagoon breeding grounds in Mexico and slaughtered close to extinction — down to maybe a few hundred individuals by the 20th century. But the whalers didn’t have it all their own way. Grey whales earned the name "Devilfish" for their aggressive response to the harpoon, particularly mothers defending their calves.

Happily, since protections were introduced, their numbers have rebounded.

"But the remarkable thing is, they have become exceptionally friendly, they approach boats — especially in Mexico and Baja, California — they seek out human contact," he says.

"I experienced this myself. I was down in Baja last February when two whales swam over to my boat and stuck their heads out of the water and I put my hands on them — it was absolutely insane. And you think, ‘here’s a species that was dangerous and frightening and it reacts totally differently to humans today’."

It could be that Gigi had a role to play.

During her time in captivity she formed attachments to some of her keepers and her release back to the ocean lines up nicely with the first "friendly" interactions with grey whales — the culture seemed to have changed.

Whale watching in Mexico would be impossible without that change, Prof Jones says. It implies Gigi learned something about humans, and other whales learned from her.

At the same time, the encounters her captivity afforded scientists and the public helped shape the direction of research and perceptions of the species.

"It helps us understand that whales are capable of a kind of cross-species communication — that given the chance they can be folded into the human family," Prof Jones says.

"It allows us to think creatively and expand our own boundaries of what kinship might mean."

Of course, it’s been a brutal kind of kinship for some of our shared time.

As the book details in several chapters, in recent centuries it was the lure of whaling that drew countries into the Pacific.

"It is a story of unrestrained slaughter," Prof Jones says. "It is a story of colonial exploitation in many cases. Whaling I think more so than anywhere else in the world was central to colonialism in the Pacific. This was an ocean more full of whales than any other ocean and it was an ocean where people around the Pacific had really special relationships with whales, so whales were very much tied up with the colonial story here."

For example, when the Japanese expanded northward to the island of Hokkaido one of the strategies they used was taking drift whales — whales that had died and washed up on shore — from the indigenous Ainu. Ainu depended on them for food. Russians did something similar in Alaska, confiscating whale meat.

"This was a powerful tool of colonialism. It was a way to subjugate people whose lives were deeply wrapped up with whales.

"Power is always right in the centre of the story of humans and whales. Human power over each other, human power over whales, but power didn’t always move in exactly predictable ways, local knowledge of whales could be really powerful, could help resist colonialism."

Prof Wanhalla’s chapter in the book takes a look at one of these other stories, where the lines are not quite so clear and power was arguably more diffuse. It also rubs at the dividing line between land and sea, that arrived in the Pacific with colonisation.

Written together with Kate Stevens, of the University of Waikato, her chapter looks at Maori women involved in shore whaling in southern New Zealand.

Prof Wanhalla has long been interested in cross-cultural relationships, and the pair investigated how that played out around the southern coast as the important new economic activity of industrial whaling dropped anchor.

They began looking at southern whaling stations both as economic entities but also sites of kinship and connection between families.

Māori women were marrying into whaling station communities, or, as Kāi Tahu would argue, the whalers were marrying into Māori communities, making Māori women the key hinge holding those two elements, economic and kinship, together.

"So, the whaling station is an economic world, it is a social world and it is also a Māori world, in which Māori knowledge or mātauranga Māori centred on Māori women’s skills and expertise."

Māori women’s medicinal knowledge, for instance, was critical to survival, alongside food production activities such as gardening and gathering from mahika kai.

"Women’s knowledge of the ocean is actually a really important part of those whaling worlds too. We want to break away from a story of Māori women, or Kāi Tahu women, as simply just the wives of whalers — it is not that simple."

It’s true elsewhere, Prof Wanhalla says.

They looked at indigenous communities in Massachusetts, on the US east coast, where menfolk were going out on whaling ships, but could only do so because the women in those communities had the leadership capacity to look after everything on shore, economically, socially and culturally.

"What we are trying to suggest is that the whaling world of the water is not disconnected from the world of the land at all and we can explore that through women’s lives."

For Kāi Tahu, who saw no hard dividing line between land and sea, it would have been natural to see the world as connected in that way — the work of women maintaining the life of the shore station just as essential as the success of the offshore enterprise.

"There is mana in women’s expertise and knowledge, that was part of what we were trying to tease out in some of the archival material we were looking at."

"It is all about skill and expertise and knowledge, not about gender," Prof Wanhalla says.

Indeed, restrictions based on gender and gender roles tended to come in with colonisation.

"Which doesn’t really work in te ao Māori, because gender doesn’t matter when it comes to leadership, skill and expertise."

While there’s no one story, Prof Jones is prepared to share a general assessment of the business of whaling in the Pacific.

"I think whaling was a pretty bad process in most ways, for the Pacific’s history. It was something that degraded the environment, the ocean in particular, it robbed people of resources, especially in places such as Alaska where people depended on those resources from the ocean. ... The story is mostly pretty grim, there is no question about it."

It’s a story of capitalism off the lead.

"One can’t understand the history of whaling without capitalism, the financing that was necessary to fund these long voyagers, the profits at home that were part of a market economy, none of these stories really make sense without capitalism."

The book explains the complicated relationship whalers had with their prey, arriving at an intimate knowledge of their behaviours and admiring the way they cared for their young, but compelled to slaughter by the "lay" system, that gave them a percentage of profits.

Whales are an incredible story of the 20th century, Prof Ryan says, we nearly wiped out this creature that is so hard to destroy.

"They live in the most remote parts of the ocean and yet we still collectively as a species almost did it. It was really close by the early 1970s, blue whales were down to a few hundred individuals. A remarkable story, I suppose a metaphor really for some of the greatest excesses of the 20th century, so it should give us some hope, that we have seen the rebound in the last 50 years that we have."

We should appreciate that not everything is a tale of doom and gloom.

"The only way that we were able to accomplish that was by different people from different parts of the globe actually getting together and agreeing that we needed to change something. It was a pretty remarkable form of human cultural change. I think it is really an unbelievable story."

There was no perfect agreement, but we were able to find enough agreement to head off total disaster.

In these years since the tighter regulation of whaling in the 20th century, our relationship with whales remains on the move, Prof Jones says.

"Are we united about whales? No certainly not. The Pacific is still rich with all sorts of different ways of thinking about whales. They face new challenges today. They face plastic in the ocean, they face shipping noise — probably the biggest problem for whales — and ship strikes, the globalisation of the last 30 years by some measures has been as bad for whales as was industrial whaling. By some measures.

"And these are brand new questions that require us to think creatively about our relationships with whales. It requires us to think about science, but more than that — the science of whales — the alchemy of human relationships. How do we make decisions about how we are going to interact with whales, as kin, as commodities, as symbols of the future?

"Hopefully this book allows us to think about where we have been and where we might want to go in the future."

And whales are more numerous now than they were 50 years ago. We’ll see more of them, they are a bigger part of our lives, thankfully, he says.

The book speaks to the fact that it matters how we think about whales in artistic and imaginary and literary terms, as much as it does in scientific terms. The science of whales is essential, but the way human communities form around whales is an act of imagination too and an act of community that is important to understand as well, Prof Jones says. We can’t really hope to understand our relationship to whales without thinking about how our ancestors managed these relationships and what it meant for them in the past.

Paikea rides over the horizon again in this context in the book’s final chapter, in which Dr Billie Lythberg and Dr Wayne Ngata tell the story of Paikea the tekoteko, the carved gable figure, now held in New York’s American Museum of Natural History.

After it was rediscovered there in 1990, members of Te Aitanga a Hauiti, the East Coast iwi whose marae it once graced, journeyed to the museum to reconnect their whakapapa, and gifted Paikea the tekoteko a whale’s tooth pendant.

Further south, Paikea is there again in the story of Whale Watch Kaikōura.

It was founded by Kāti Kura, an iwi that claims descent from Paikea through his youngest son, Tahu Potiki.

Iwi elder Bill Solomon looked to the past and to their whale-riding ancestor at a time when their town was at a low ebb, Lythberg and Ngata write.

It’s a great example of new connections, in which Māori and tourists work together in relatively benign way, benefiting everyone, Prof Jones says.

And the iwi’s partner in the enterprise just happens to be sperm whales.

"The classic prey of the American whaler."

- Across Species and Cultures: Whales, Humans and Pacific Worlds, edited by Prof Ryan Tucker Jones and Prof Angela Wanhalla.