Steve Tripp is chuckling away, laughing about a trap he’s set for some friends.

"I look forward to seeing the mess at the end," he says, still laughing through a mouthful of very healthy looking lunch.

That may or may not happen. For as Tripp is well aware, his friends know about the trap too. And not only that, but there are some mighty tough hombres and mujeres among them. They might just charge straight through it.

What Tripp is so amused by is a section of Dunedin’s new ultra-distance running race that will have competitors plunging down a long winding descent from the top of Flagstaff, via Longridge Rd, to Whare Flat.

On the race website it is described like this: "a great place to get your fastest ever 7km if you want to smash your quads early on".

You can hear Tripp grinning as that was written. And possibly this next bit too: "Now the fun stuff starts". Because once the runners have given up all the hard-won metres to the top of Flagstaff and find themselves down on the Taieri, Tripp’s sending them up a long, long ridge-climb into the Silver Peaks.

"This is the longest and toughest leg of the race with three stream crossings, lots of mud, a brutally steep uphill ...," the description continues. And some nice views, it adds.

The running was to have been back in March but then Covid-19 happened. It is rescheduled for October 11, which means the tracks are likely to have more of that mud than originally planned.

To clarify, an ultra is essentially anything longer than a conventional marathon distance — so upwards of 42.2km.

The preserve of a hardy few? You might very well think that, but there’s growing evidence to the contrary. Well, the hardy bit is almost certainly accurate, it’s just the "few" that might be in question.

Tripp cites the recent publication of the book The Rise of the Ultra Runners (subtitle: A Journey to the Edge of Human Endurance), by Adharanand Finn.

"He reckons that it is the fastest growing sport in the world, ultra running," Tripp says.

Finn found evidence that events have grown by more than 1000% in a decade while participant numbers are also booming, perhaps helped along by people’s desire to find the next hill to climb — so to speak — after completing a marathon. Some of the better known events run lotteries to enter, such is the demand.

The increasing costs — financial and regulatory — associated with organising running events on public roads has probably also helped hand the baton to the mainly off-road ultra scene.

Whatever the case, the races are most definitely on. There’s the 52km Motatapu, the 60km Kepler Challenge (which typically sells out in minutes), the 100km and 100 mile (160km) Northburn, the Great Naseby Water Race, which offers a 200-mile option, and the 323km Alps to Ocean ultra — run over a week in February. And that’s just some of those in the South.

Now there is the Three Peaks Plus One.

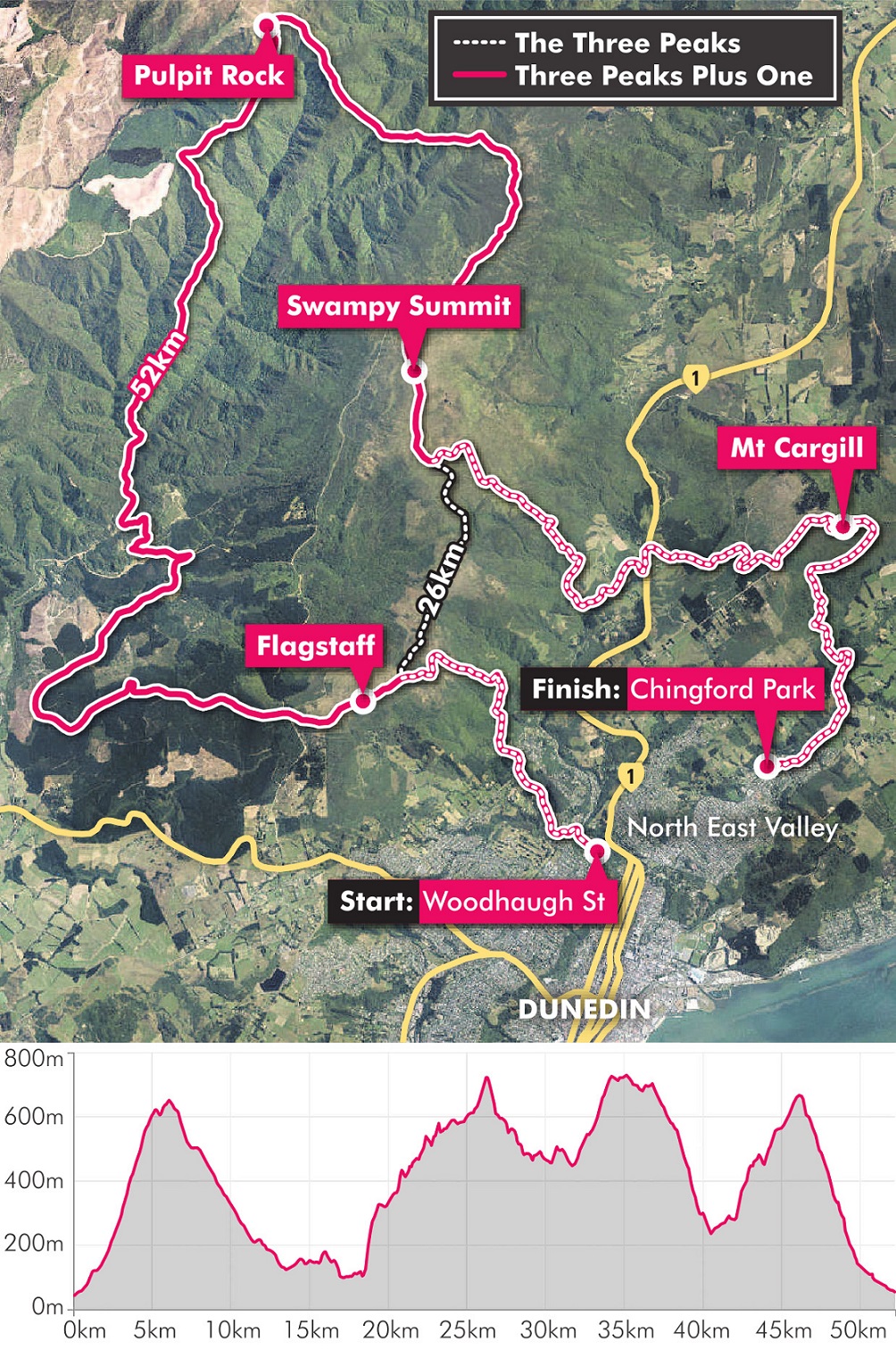

Leith Harriers has been organising the 26km Three Peaks Mountain Race for decades, which takes entrants from Woodhaugh up Flagstaff (670m), across to Swampy Summit (740m) and Mt Cargill (680m), then down to Chingford Park in North East Valley. There over a couple of hours a loose conga line of celebration runs, staggers and collapses across the finish line, people from all walks of life expressing an uncomplicated, simple joy and relief. Because they have finished. Some in a little over two hours, some in four hours and change. They have come down from the mountains, richer for the experience.

Leith has capped numbers at 400 this year, with wave starts to keep it Covid compliant. Most will do the 26km course, but up to 100 will add Silver Peaks’ Pulpit Rock (750m) to their day out — the Plus One ultra.

"It was probably me pushing Leith Harriers to say, hey, let’s do something different," Tripp says, confessing to his role initiating the ultra, "recognise the 26k is a really iconic race — it’s been going since 1984 — but to attract people from outside Dunedin, because there are so many larger events, they are not going to come to a smaller event."

We should mention Tripp has form here. Since returning to Dunedin he’s also started the community fundraiser Crush the Cargill, a 24-hour race up and down Mt Cargill.

"I think we should sell our hills and trails better," he says. "It is a real gift that Dunedin has. More so than other places, especially larger cities in New Zealand."

That’s all very well. We have nice hills and good trails. So pull on a pair of stout walking shoes and go for a hike. But run up them?

Tripp’s own journey into this world helps explain.

His first ultra was back in 2014, the Northburn 50km, a notoriously testing course involving a lot of "elevation"; which is to say, running up and down. Before then he’d done some marathons, having taken up running at age 40 to keep fit.

"When I started trail running, moved from road to trail running, it was like ... life started," he says, with another huge smile but a good deal of sincerity.

A medical teaching fellow at the University of Otago’s Department of Physiology, Tripp sees ultra running playing a similarly significant role in the lives of many others.

During our lunchtime interview, he’s been talking about the way in which he craved green, on returning to New Zealand after seven years working in Cambodia, and found it in the hills. However, when asked if that’s the main draw for most people, the scenery, the environment, he says he thinks probably not.

"I would say, no, actually. I would say they are an added bonus. I think people do it because they want to push themselves, and they want a challenge. It is a sense of achievement. For many people I meet it is a mental health thing. It keeps them sane.

"The ultra running itself, you know, sometimes you have those high moments but you also have the lows and it is getting through those lows and coming out and finding another high, and knowing you are going to go through those cycles.

"Everyone talks about it as a metaphor for life," he says with a chuckle.

It’s a sport that appears to provide the variety of life: there’s a strong sense community and common purpose, but it’s simultaneously about individual effort and replete with time alone.

"It’s both," Tripps says. "To get all spiritual here, I think humans need a mixture of solitude and community and you can’t get the best of one without having the other. And I think long distance running actually provides both, in quite a deep way. So some people, I think, find it really difficult, the solitude, but it is also essential. But then some people find community really difficult, and it’s essential."

Then there are the natural endorphins, brought on by the exercise, he adds.

"Don’t forget the high," and laughs again.

Among the runners who will be tackling Tripp’s 52km endorphin machine, is Orlaith Heron. During working hours she’s a Dunedin Hospital oncologist. After hours she’s in the hills.

So she’s smart and she’s fit, and she’s also on to the race director.

Unprompted, she says the one tactic she has plotted for the Three Peaks Plus One is to not "kill my legs on the gravel downhill".

That’s the section Tripp was laughing about earlier.

Heron’s is the voice of experience. Not only is she a former Three Peaks (26km) place-getter, but she’s racked up a whole pool room of ultra achievements; among them the 85km Old Ghost Road, the 85km Tarawera, the 50km at Naseby, and 107km at the Ultra Easy. We can assume that last wasn’t easy.

There was also a DNF (did not finish) attempting the 100-mile Northburn (a "miler"), due to a gastro bug.

"Courtesy of my partner. I have never forgiven him," she says, possibly not joking.

Heron’s pathway into trail-running and ultras is not so very different from Tripp’s. And similarly it has become an important part of her life now. Both the time alone, running the hills, and the community aspect.

An Irish import, Heron found that running trails was, early on, a good way to see the country.

What happened next, was that she wanted to keep going. It was fun, exhilarating, literally full of twists and turns.

"I just didn’t want to stop essentially, which is very different to how I feel when I am on a road.

"I can’t think on a trail. People talk about going out to do a sport to mull over a problem. When I go out on a trail I completely forget. I cannot think about anything, I just go into some kind of dream world. All I can see is what’s around me."

After that, it’s about the people, and the "random" chats you have with someone you run alongside for a while.

"In a short race you almost can’t chat because you are huffing and puffing but in an ultra you will be walking bits, you’ll be eating lots," Heron says. "If people are going at the same pace as you at a certain time, you are just going to hang on to each other and have a chat, have fun."

Tripp says the events are in many ways just diary entries to help motivate. The important thing is the training itself, the running itself.

And indeed, Heron says her longest run — in terms of time on her feet — was in fact not an event at all, but rather a night-time run along the 80km Hillary Trail, in the Waitakere Ranges.

With a group of friends, she set off at midnight on a midsummer’s night.

"The moon was pretty spectacular. There were periods when you almost didn’t need a head torch it was so good. Then sunrise was pretty magical."

You clearly need to be in some sort of shape to take these challenges on, but Heron gives the impression of taking a fairly laissez faire approach to training.

Trail-running, as with all hobbies, is like a relationship, she says. So, trying to stick to too prescriptive a regime will just make for a difficult relationship.

Rather, Heron does what she can and goes with the flow.

"I went out into the Silverpeaks last weekend and I went out for six and a-half hours because I got lost," she says.

The plan was for a three and a-half hour run.

It wasn’t a problem though.

"I had enough food."

She backtracked, found a familiar trail and carried on.

Either hot on Heron’s heals, or vice versa, on October 11, will be Dunedin woman Sharon Lequeux.

She runs marathons but at other times likes to do some running for fun. Like say, ultras.

She has already crushed Tripp’s Mt Cargill 24-hour race, good and proper, a couple of times. Including running up and down 15 times in less than 24 hours; completing about 125km and 8500m of elevation.

So, given neither Tripp nor Heron have so far described any particularly dark moments on the trail — that time when the legs were shot, the will was weak and the lungs were no longer respiring with any enthusiasm — I asked Lequeux: "What’s that like?".

Lequeux said she didn’t know. Or at least she’s never met a moment that a little more coffee couldn’t fix.

She does admit to finishing before the 24 hours were up on the Crush the Cargill.

"I stopped a little bit early. Like maybe after 23 hours because there’s not much point going up for another lap if you are not going to make it before the 24 hours are up."

It all seems to boil down to this: "I guess, I like running," Lequeux says.

But then, just maybe, the merest hint of an alternative fact. Asked whether she had to think long and hard before signing up for the 52km, Lequeux admits she did. However, it turns out that was only because she’d have liked to run the 26km race again. She won it last time.

"Oh, it will be great," she says of the Three Peaks Plus One. "We’re pretty lucky to have the Silver Peaks in our backyard."

And if Lequeux is not yet making it sound sufficiently like some sort of backwoods picnic, she adds that she’ll probably be packing homemade fig-based bliss balls for sustenance.

"Maybe a caffeine shot or some dried banana."

There appears to be little or no sense of trepidation whatsoever.

"You are just out there doing what you love," she confirms.

Heron reckons Tripp’s course is something like a seven-hour prospect.

Tripp says some might get around in close to five hours (depending on the mud quotient). Others could take 10 or 11 hours; running, walking, stopping, eating (bliss balls or something else), drinking, talking. Alone and with others.

Being human.

The race director is among those who regard distance running as something elemental for our species, one of our quintessential characteristics.

"I’ve read some of the anthropological research as well as biological and environmental stuff. I am probably biased ... But whenever I have read stuff on it, it makes really good sense, it kind of fits with both evolutionary theory, anthropology research," he says.

The science to which he refers, argues our distant hominid ancestors had to learn to run when they came down from the trees, developing a "striding bipedalism" that was supported by changes to our physiology, bone structure, the development of a stronger gluteus maximus, our ability to perspire and avoid overheating. We evolved to stride and stride.

"We are born to run," Tripp says.