As summer nears, thoughts will turn to that most celebrated of Kiwi activities, when we throw open the doors to our backyard and ritually release long-buried fossil hydrocarbons into our already overheated atmosphere.

Yes, it is almost time to fire up the gas barbecue.

Or not.

Because the LPG bottle that has been quietly leaking away in its corner of the garden shed over winter, is full of climate-heating fossil gas. The stuff we need to stop burning, fast.

Relax, though, barbecue tragics. Put the flaming torch and the pitchfork down. You need not worry for the moment. While He Pou a Rangi the Climate Change Commission has been nudging the government towards a phase out of fossil gas for a while now, as part of efforts to meet our international climate obligations, its latest draft advice specifically excluded LPG barbecues from that effort, alongside camping cookers.

For now, carcinogenically blackened offal is safe — kind of.

More broadly, though, that sputtering noise you can hear is indeed the gas hob running down, the unflued lounge heater giving up its last.

Because the government is putting together a plan for the end of gas as we know it — as part of a National Energy Strategy due next year.

New Zealand’s bigger picture shift away from fossil gas was launched recently with the release of the Gas Transition Plan Issues Paper, by Hīkina Whakatutuki the Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment (MBIE). In its foreword, Minister of Energy and Resources Dr Megan Woods says we need to do things differently if we are to avoid the impacts of climate change.

In short, it says we will use much less fossil gas in future, and if your gas stove remains operational, it needs to do so on the basis that we have found a miracle way to produce large quantities of biogas from waste.

It would be a stretch to describe us as fast followers on this one. Elsewhere, they have already begun turning the fossil gas taps off forever.

Most recently, the Australian state of Victoria declared it will allow no new fossil gas connections in new homes or government buildings from next year. It makes Victoria the second Australian state to do so, after the Australian Capital Territory, while Sydney’s local authority has agreed similar measures for the New South Wales city.

Victoria’s decision looks like a winner all round after an Environment Victoria report found households could save up to 75% on their winter heating bills by switching to the likes of heatpumps.

It is not just Australia either. Germany is among European countries looking to wean itself off gas for domestic use, considering a ban on new fossil-fuel boilers from as early as next year.

In the US, dozens of cities, including New York and Los Angeles, are either banning or discouraging new gas connections for appliances — though there of course it has become part of the culture war. Even the name of the stuff, natural gas vs fossil gas.

Assoc Prof Tim Nelson, of Queensland’s Griffith University, backs the move away from gas in his country.

"In so many ways our economies can be made more efficient by switching from gas to electricity and that is particularly the case for households," Prof Nelson, an economist and member of Australia’s Climate Council, says.

"The fact that electricity in the home is so much more efficient, makes it an overall much more economic energy source for things like cooking, spatial heating, heating hot water.

"So electrification of the home is not just a great way of reducing emissions and staying within a carbon budget, it is actually a great way to save money."

While the big driver of the move away from fossil gas is the climate, health concerns long linked to fossil gas use in the home remain part of the picture.

University of Otago public health researcher Assoc Prof Alex Macmillan says using gas at home, particularly unflued heaters, increases the risk of respiratory disease such as asthma.

"Burning gas inside people’s homes comes with an air pollution cost, including carbon monoxide and oxides of nitrogen and moisture that all cause disease in people’s homes, including asthma."

Health inequities tend to be part of that picture, she says, and we have clean energy alternatives that can address that, which are all electric.

A study published in the British Medical Journal found nitrogen dioxide could exacerbate respiratory symptoms, reduce immunity to lung infections and increase the severity and duration of an episode of flu.

A recent US study found that, quite apart from the health impacts on households, unburned methane emissions escaping from America’s gas stove tops were comparable to the annual carbon dioxide emissions of 500,000 cars.

He Pou a Rangi the Climate Change Commission’s first draft advice to government back in 2021 recommended setting a firm date after which no new fossil gas connections, or bottled LPG connections, to buildings should be permitted.

"This should be no later than 2025 and earlier if possible," the commission wrote.

The 2025 deadline didn’t make it into the commission’s final advice to government that year, but the commission’s latest advice, from April this year, still talks about a prohibition on the new installation of fossil gas in buildings.

The commission says that would safeguard consumers from the risks of locking in new fossil gas infrastructure.

Energy consultant Scott Willis says the government needs to show leadership, in particular to safeguard the interests of domestic users.

Without that, domestic gas users could be caught out by the rising cost of fossil fuels.

Industrial players are already focused on decarbonising their operations and actively seeking advice so they can make good commercial decisions, he says. That means the big risk sits with domestic consumers, households and particularly the hard-to-reach households who do not have access to that market information. As a result they may well make poor decisions, and invest in the wrong technology, get stuck with gas appliances, whether for cooking or water or space heating, potentially locking in energy hardship.

"So the risk we have is that we will have our most vulnerable stuck with technology that they can not use, or is so expensive to use that they are making a choice between heating and eating."

Willis, who is a Green Party candidate in this year’s election, says what is required is government support for the transition away from fossil fuels, in people’s homes, including grants and loans to shift to heat pumps and induction cookers, as well as improve insulation to reduce energy costs overall.

The MBIE paper flags the issue too.

"There is a risk if consumers rapidly switch away from fossil gas that this consumer segment will be burdened with a rapidly increasing share of pipeline costs," it says.

"We may need to develop complementary support programs [sic] for low-income users and renters who are unable to respond to rising gas prices by buying electric appliances."

Which is to say, the few remaining gas users would be faced with the upkeep cost of a billion-dollar gas network.

The risk is already manifesting. Besides the impact on fossil gas prices of the Emissions Trading Scheme, the Commerce Commission last year approved increases to gas prices to protect gas infrastructure in the face of a climate-driven exit from gas by consumers.

Demand for fossil gas is expected to decline and the remaining life of gas pipelines in New Zealand is likely to be shorter than previously expected, the commission said last year.

In the face of that decline, pipeline companies would need to charge more to maintain their infrastructure.

While the increase approved by the commission, of about 3.8% a year, "does not provide a guarantee that gas pipeline businesses will recover the full value of their investments", it said the decision took into account the need for pipeline businesses to maintain safe and reliable supply while demand remained.

The commission also shortened the period until its next review of prices to four years, the shortest period available to it.

It is tricky situation, given the savings awaiting those who can move away from gas first.

Climate commission analysis shows that New Zealanders who can transition their households to all electric appliances and use an electric vehicle by 2026 stand to save thousands of dollars in the long term.

It reads like a strong dollars and cents argument to speed the transition, which is what Prof Nelson is backing in Australia, but it requires leadership.

"The sooner governments make decisions about phasing out gas, the more thoughtful the recommendations can be about how to deal with that issue and allocating the costs and risks," he says.

Australia’s transition away from fossil fuels includes growing quantities of solar, one in three houses there now sporting solar panels, alongside wind and storage options including both batteries and pumped hydro.

"Renewables continue to become more cost effective," Prof Nelson.

"And the beauty with renewables, once you have built them you know what the cost is because you paid for them, the sun and the wind are free."

As the MBIE paper sets out, New Zealand’s gas sector comprises both fossil gas and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), for both of which, renewable alternatives exist — though not on any scale.

In 2021, net fossil gas production in New Zealand was 157.5 petajoules (PJ).

That same year we used 9.4PJ of LPG. Almost half of that was the 45kg market, used primarily in homes and businesses. The 9kg market supplying smaller appliances such as barbecues and heaters is about 10% of the LPG market.

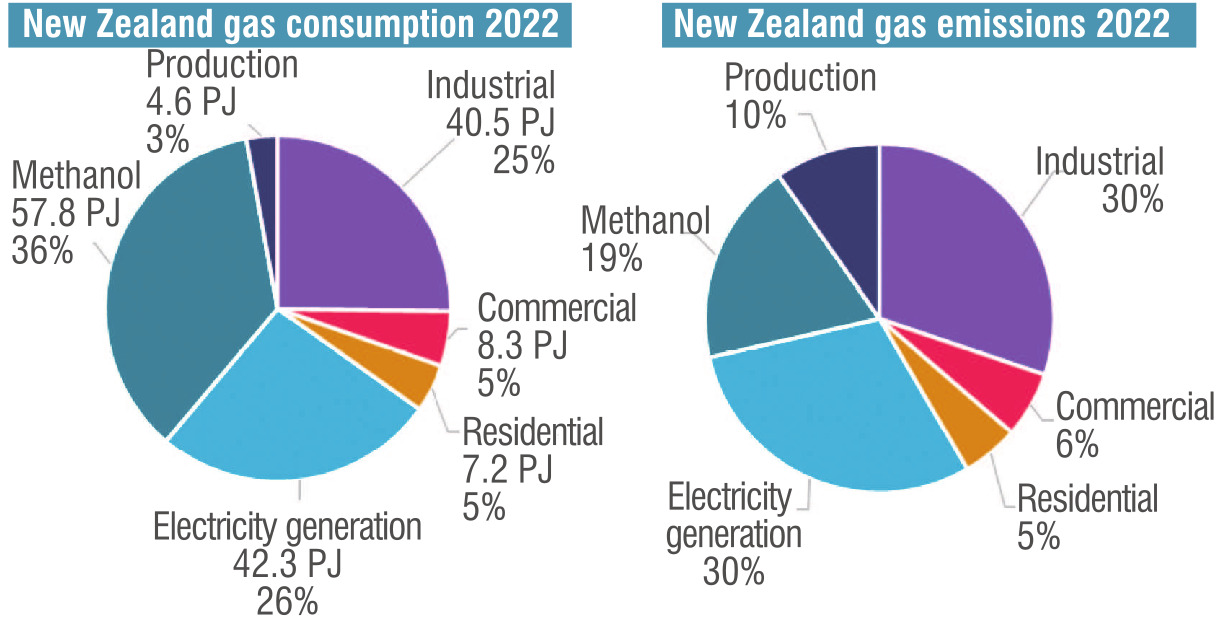

Fossil gas users range from petrochemical manufacturer Methanex, which makes methanol for export — by far New Zealand’s largest energy consumer — to 306,000 household connections.

Those residential connections consume about 5% of the fossil gas total, 7.2PJ, and produce about the same sized chunk of the carbon emissions.

Altogether, carbon emissions from gas make up about 21% of energy and industry sector emissions.

It’s a lot of energy, and GasNZ — a recent merger of the Gas Association of NZ and the Liquefied Petroleum Gas Association — is bullish about renewables meeting some of the demand.

It’s website homepage — verdant green hills without a pipeline in sight — declares "a cleaner future is coming".

"Biogas is a really big part of it," GasNZ chief executive Janet Carson says of that future.

"What we have to do is dial down the natural gas, we know that, we accept that, that is a very very good thing to do. No doubt about it."

But what the country’s energy system looks like on the other side of that transition remains to be decided, she says, and can include biomethane, renewable LPG and green hydrogen.

"The opportunity is definitely not greenwash, I will say that hands down," Carson says. "I am not interested in greening natural gas, I am interested in solutions for the country, energy solutions but broader environment solutions."

However, the prospect of renewable gases playing a big part in the transition look remote. The MBIE paper estimates the potential of biogas by 2035 at no more than 7PJ, a small fraction of the fossil gas used now. And even the cheapest 2PJ of that, from waste digesters, would be twice the current price of fossil gas.

Carson says the 7PJ is a conservative estimate and suggests the fossil gas industry’s preferred way forward would be for the government to mandate a percentage blend of renewables in fossil gas. She nominates a 5% mix of biogas by 2035.

"I think 5% is material," she says.

Material or not, MBIE sees renewable gas running into the same problem as fossil gas, relative to electricity.

"We expect pipeline fossil gas demand to eventually decline due to electrification, and increasing carbon prices, regardless of whether it is blended with biomethane," the paper says.

The prospects for renewable LPG look a little better, as some of its traditional uses are more difficult to replace, but even there, competition for the feedstock to make it means it is likely to cost more. One industry commissioned study pins renewable LPG’s future on finding an economic way to collect Canterbury’s cow dung and turn it into gas.

Willis is clear that the focus needs to be on exiting from fossil gas as quickly as possible.

"Gas is a fossil fuel, we need to ensure that we are transitioning out of gas, almost as fast as we transition out of coal."

Any proposals to extend the lifetime of gas need to be measured against already available renewable alternatives such as wind and solar, he says.

Nelson adds the rapid reduction in the cost of battery storage to that picture, it has been the big technological development of recent years, he says.

In Victoria, the state government is funding a Neighbourhood Battery Initiative, putting shared batteries into communities to store excess rooftop solar during the day and shift it into the evening peak.

"There absolutely are ways of solving the electricity demand issue using non-gas fuels," Prof Nelson says.

"You can move away from gas and coal simultaneously through the use of some of those technologies."