The worst moment, a standout among many bad ones, was when Brenda's brother sent a letter to her son.

It was a photocopy of a letter from the Police, acknowledging the brother's complaint alleging Brenda [not her real name] was stealing money from her parents.

For years, the relationship between the Dunedin mother and her siblings had been fraught. But things nose-dived as their parents became elderly, needed rest-home care and then died, leaving a sizeable inheritance.

The letter was a new low. It was sent to the teenage boy, with a handwritten note: "Sorry mate, but your Mum is a thief - Jail time for her. Have a nice day".

"I just about had a breakdown over it," Brenda says, on the verge of tears. "It's just been the most stressful time."

Inheritances are a taboo topic in New Zealand.

But court documents and Ministry of Justice statistics lift the covers a little on this hidden world.

They reveal that in recent years, there has been an average of 313 estate dispute cases per year in the Family Courts and High Courts.

That includes an average of 13 estate disputes each year that end up in Otago and Southland courts. Although, the real number for the lower South Island is probably significantly higher because cases disputing whether a will is in fact the person's last valid will are filed directly with the Wellington High Court.

Those are the bare figures. Judicial decisions posted online by the Ministry of Justice put flesh on those bones.

On October 30, 2017, for example, in the Dunedin High Court, Associate Judge Osborne gave his ruling in an estate dispute that spanned three generations.

A man and his three children had sued the executor of his step-father's estate.

Through their lawyer, the man and his children argued the step-father should have made provision for them in his will. They said the step-father had an agreement with his late-wife to provide for her son and his children, but that the step-father had not done that in his final will.

The judge found that while it was likely the couple had agreed that the grandchildren would be looked after, it "fell short of legally enforceable commitment". The final will stood.

In a sequel, a month and a-half later, the judge ordered the plaintiffs, the man and his children, to pay the defendant's legal costs, which amounted to tens of thousands of dollars.

About the same time, the Court of Appeal was hearing an Otago-based case. A nephew and four nieces of a deceased woman, who had lived in Mosgiel, were appealing a 2016 decision of the Dunedin High Court, which had not gone their way.

In 2013, their aunt had written a will leaving "my house unit at Chatsford" to a particular friend who she named. She also left $648,000 to be divided equally between her nephew and nieces, her jewellery and ornaments to her nieces, $440,000 in legacies to various other people and forgave any debts owed her.

Four months later, she died.

The nephew and nieces filed a suit against their aunt's lawyer, who was also the executor and trustee of the estate. Their argument was that the gift of the house unit at Chatsford, a retirement village, "failed".

The aunt did not own the unit. Instead, she had a "right to occupy" agreement with the retirement village. So, she could not gift the unit to the friend. In light of that, the nephew and nieces argued they should be made the beneficiaries of the $291,000 that the retirement village would pay under the termination and improvements agreements on the unit.

In the Dunedin High Court, Justice Nation said the lawyer should have used different words when drafting the will. But, it was clear the aunt had intended the friend to be the beneficiary of her interest in the unit, and that was what should happen, the Judge ordered.

The Court of Appeal judges disagreed with their High Court colleague's process, but agreed with his conclusions. The money from the termination of the unit agreement was to go to the friend, they said.

What Judges' summaries only hint at is the acrimony, the bad blood and fractured relationships that can come from nowhere when a death in the family and the prospect of sudden gain coalesce.

These scenarios are only likely to become more common as two other forces collide: Baby Boomers are moving towards old age and the next generation is not as materially well off as the previous one.

Birth rates took off after World War 2. Those babies are now aged between 54 and 74 years old. But time is relentless. In a decade, the Boomer bubble will be approaching the far end of the population python. By 2028, the number of people who have reached the forecast life expectancy in New Zealand will have grown by almost a third.

That's a third more wills and estates to fight over.

And people will be more motivated to do so. Inheritances are becoming increasingly important as stagnant incomes and unaffordable housing continue to bite deep. This was highlighted in a report released last year by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The world's leading economic think-tank said the wealth of cash-strapped younger generations now depends more on how much they inherit.

In Brenda's case, in the end, the parents' written wills were clear and their wishes fulfilled. The mother's estate was divided between the children and the grandchildren. The father's, split equally between the kids.

But on the way to that point there has been a steady stream of rancour and downright nastiness. There have been accusations of pilfered jewellery. There have been offensive messages left on phones. The only copy of their mother's will went mysteriously missing for several months. Attempts were made to wrest enduring power of attorney from Brenda. Some family members wanted the father's assets dispersed before he died. The day of her father's funeral, a nephew messaged Brenda asking for a breakdown of properties owned and their values.

But all those paled when compared to the allegation of fraud.

Brenda had enduring power of attorney for both parents, who had dementia.

She oversaw payments from her parents' bank accounts for costs including her mother's regular hairdressing and podiatry appointments and three years' of thrice-weekly outings with her father.

But in late-2017, after the parents died, two of her siblings made a formal complaint to Police, alleging Brenda had unlawfully used tens of thousands of dollars of their parents' money, their inheritance.

Last year was hell, Brenda says.

She was interviewed multiple times by detectives, twice on video.

"I was offered a lawyer. But I said, I don't need one, I haven't done anything wrong."

Police statements were taken from rest-home staff, a real estate agent, siblings, her father's best friend ...

The investigation dragged on throughout last year.

"It's been pretty soul-destroying, actually," she says, with feeling.

The prospect of more such estate disputes within families is bad enough. But an even bigger problem is the hidden way inheritances exacerbate inequality, Max Rashbrooke says.

A wealth and inequality researcher, Wellington-based Rashbrooke says little is known but a lot can be inferred about the damaging effect inheritances are having in New Zealand.

What we do know is that there is substantial wealth inequality in New Zealand, he says.

"That's a very high level of inequality," he says.

"I saw some OECD figures just this morning ... We are certainly not the most unequal, but we are among the most unequal.

"We have radically changed compared with the early-1980s."

What we also know is that inheritances are inherently unfair.

"In one sense, gifting inheritances is a completely understandable practice: everybody wants to be able to pass something on to their children," Rashbrooke explains.

"It is also, simultaneously, profoundly unfair: nobody has deserved their inheritance by virtue of the fact that no-one deserves their parents."

To know how inheritances and inequality are interacting, we have to look to the United Kingdom (UK), he says.

The two countries have almost identical levels of wealth and income inequality. But on top of that, the UK has detailed data on inheritances.

Rashbrooke quotes UK researcher John Hills.

"Among all those who inherited between 1996 and 2005, around half of the total of all inheritances in the decade went to the top 10th of inheritors, that is, to around 2% of all adults."

This, Rashbrooke says, makes it clear that in the UK large amounts of money are being given as inheritances and that they profoundly reinforce inequality.

The worst moment, a standout among many bad ones, was when Brenda's brother sent a letter to her son.

It was a photocopy of a letter from the Police, acknowledging the brother's complaint alleging Brenda [not her real name] was stealing money from her parents.

For years, the relationship between the Dunedin mother and her siblings had been fraught. But things nose-dived as their parents became elderly, needed rest-home care and then died, leaving a sizeable inheritance.

The letter was a new low. It was sent to the teenage boy, with a handwritten note: "Sorry mate, but your Mum is a thief - Jail time for her. Have a nice day".

"I just about had a breakdown over it," Brenda says, on the verge of tears.

"It's just been the most stressful time."

Inheritances are a taboo topic in New Zealand.

But court documents and Ministry of Justice statistics lift the covers a little on this hidden world.

They reveal that in recent years, there has been an average of 313 estate dispute cases per year in the Family Courts and High Courts.

That includes an average of 13 estate disputes each year that end up in Otago and Southland courts. Although, the real number for the lower South Island is probably significantly higher because cases disputing whether a will is in fact the person's last valid will are filed directly with the Wellington High Court.

Those are the bare figures. Judicial decisions posted online by the Ministry of Justice put flesh on those bones.

On October 30, 2017, for example, in the Dunedin High Court, Associate Judge Osborne gave his ruling in an estate dispute that spanned three generations.

A man and his three children had sued the executor of his step-father's estate.

Through their lawyer, the man and his children argued the step-father should have made provision for them in his will. They said the step-father had an agreement with his late-wife to provide for her son and his children, but that the step-father had not done that in his final will.

The judge found that while it was likely the couple had agreed that the grandchildren would be looked after, it "fell short of legally enforceable commitment". The final will stood.

In a sequel, a month and a-half later, the judge ordered the plaintiffs, the man and his children, to pay the defendant's legal costs, which amounted to tens of thousands of dollars.

About the same time, the Court of Appeal was hearing an Otago-based case. A nephew and four nieces of a deceased woman, who had lived in Mosgiel, were appealing a 2016 decision of the Dunedin High Court, which had not gone their way.

In 2013, their aunt had written a will leaving "my house unit at Chatsford" to a particular friend who she named. She also left $648,000 to be divided equally between her nephew and nieces, her jewellery and ornaments to her nieces, $440,000 in legacies to various other people and forgave any debts owed her.

Four months later, she died.

The nephew and nieces filed a suit against their aunt's lawyer, who was also the executor and trustee of the estate. Their argument was that the gift of the house unit at Chatsford, a retirement village, "failed".

The aunt did not own the unit. Instead, she had a "right to occupy" agreement with the retirement village. So, she could not gift the unit to the friend. In light of that, the nephew and nieces argued they should be made the beneficiaries of the $291,000 that the retirement village would pay under the termination and improvements agreements on the unit.

In the Dunedin High Court, Justice Nation said the lawyer should have used different words when drafting the will. But, it was clear the aunt had intended the friend to be the beneficiary of her interest in the unit, and that was what should happen, the Judge ordered.

What Judges' summaries only hint at is the acrimony, the bad blood and fractured relationships that can come from nowhere when a death in the family and the prospect of sudden gain coalesce.

These scenarios are only likely to become more common as two other forces collide: Baby Boomers are moving towards old age and the next generation is not as materially well off as the previous one.

Birth rates took off after World War 2. Those babies are now aged between 54 and 74 years old. But time is relentless. In a decade, the Boomer bubble will be approaching the far end of the population python. By 2028, the number of people who have reached the forecast life expectancy in New Zealand will have grown by almost a third.

That's a third more wills and estates to fight over.

And people will be more motivated to do so. Inheritances are becoming increasingly important as stagnant incomes and unaffordable housing continue to bite deep. This was highlighted in a report released last year by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The world's leading economic think-tank said the wealth of cash-strapped younger generations now depends more on how much they inherit.

In Brenda's case, in the end, the parents' written wills were clear and their wishes fulfilled. The mother's estate was divided between the children and the grandchildren. The father's, split equally between the kids.

But on the way to that point there has been a steady stream of rancour and downright nastiness. There have been accusations of pilfered jewellery. There have been offensive messages left on phones. The only copy of their mother's will went mysteriously missing for several months. Attempts were made to wrest enduring power of attorney from Brenda. Some family members wanted the father's assets dispersed before he died. The day of her father's funeral, a nephew messaged Brenda asking for a breakdown of properties owned and their values.

But all those paled when compared to the allegation of fraud.

Brenda had enduring power of attorney for both parents, who had dementia.

She oversaw payments from her parents' bank accounts for costs including her mother's regular hairdressing and podiatry appointments and three years' of thrice-weekly outings with her father.

But in late-2017, after the parents died, two of her siblings made a formal complaint to Police, alleging Brenda had unlawfully used tens of thousands of dollars of their parents' money, their inheritance.

Last year was hell, Brenda says.

She was interviewed multiple times by detectives, twice on video.

"I was offered a lawyer. But I said, I don't need one, I haven't done anything wrong."

Police statements were taken from rest-home staff, a real estate agent, siblings, her father's best friend ...

The investigation dragged on throughout last year.

"It's been pretty soul-destroying, actually," she says, with feeling.

The prospect of more such estate disputes within families is bad enough. But an even bigger problem is the hidden way inheritances exacerbate inequality, Max Rashbrooke says.

A wealth and inequality researcher, Wellington-based Rashbrooke says little is known but a lot can be inferred about the damaging effect inheritances are having in New Zealand.

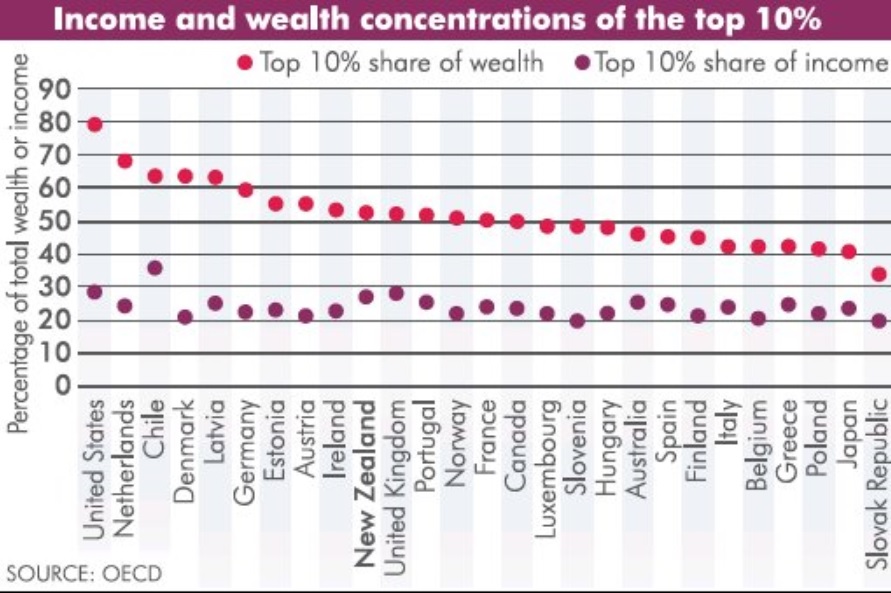

What we do know is that there is substantial wealth inequality in New Zealand, he says.

The wealthiest 1% of individuals has a fifth of all the net wealth in the country. The wealthiest 10% have 60%. In contrast, the poorest half of the country has no more than 4% of the wealth.

"That's a very high level of inequality," he says.

"I saw some OECD figures just this morning ... We are certainly not the most unequal, but we are among the most unequal.

"We have radically changed compared with the early-1980s."

What we also know is that inheritances are inherently unfair.

"In one sense, gifting inheritances is a completely understandable practice: everybody wants to be able to pass something on to their children," Rashbrooke explains.

"It is also, simultaneously, profoundly unfair: nobody has deserved their inheritance by virtue of the fact that no-one deserves their parents."

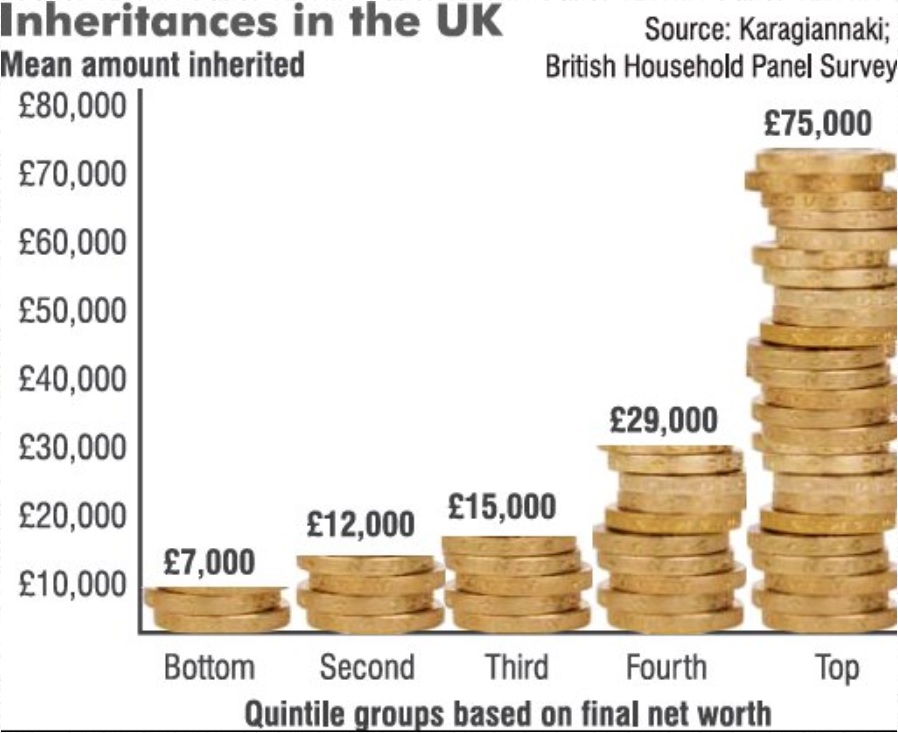

To know how inheritances and inequality are interacting, we have to look to the United Kingdom (UK), he says.

The two countries have almost identical levels of wealth and income inequality. But on top of that, the UK has detailed data on inheritances.

"Among all those who inherited between 1996 and 2005, around half of the total of all inheritances in the decade went to the top 10th of inheritors, that is, to around 2% of all adults."

This, Rashbrooke says, makes it clear that in the UK large amounts of money are being given as inheritances and that they profoundly reinforce inequality.

"Because it's the children of wealthy parents, who are already better off, who are more likely to get inheritances. So, there is a very nasty rachet effect there that reinforces inequality between families across the generations."

Patterns of inheritances in New Zealand "wouldn't be that different" to the UK, he says.

We do not know for sure, however. And that is because New Zealand does not collect data on inheritances.

Rashbrooke attributes this lack of record keeping to the persistence of the myth that we are still an egalitarian society.

"So ... there is an assumption that there isn't a huge amount of wealth transfer from generation to generation.

"But that's not the true picture. We know wealth inequality in New Zealand is substantial."

As well as the data evidence from overseas, there is convincing anecdotal evidence here, Rashbrooke says.

"It is very obvious, for example, in Auckland, that it is very difficult to buy a house if your parents can't help you.

"[Kiwi economist] Shamubeel Eaqub calls this `the return of the landed gentry'. Home ownership is becoming the preserve of those whose parents are homeowners. It's a vicious circle."

Brenda hopes the viciousness she has experienced has come to an end and normal life can begin again.

Sales of her father's properties are still being finalised. But, when everything has been sorted, Brenda expects her inheritance from her two parents will be worth about $250,000.

It is a tidy sum that will pay the mortgage off, which "of course" makes a difference, she says.

On top of that, late last week, she received the letter she had been longing for.

It was from the Police; an official declaration that she had been cleared of all wrong-doing.

"There has been no criminal offending on your part," the letter states.

"The matter is now at and [sic] end."

For Rashbrooke, the urgent matter of addressing the role inherited wealth plays in inequality has barely begun.

What is needed, he says, is solid data about inheritances, a public conversation about their role in inequality and then steps to redress the imbalance.

When significant inequality emerged in late 19th-century New Zealand, the Government responded by ending land monopolies and then introducing inheritance tax, death duty and gift duty.

The Tax Working Group, which recently gave its final report to the Ardern Labour-led Government, was told not to look at inheritance tax. That was a missed opportunity, Rashbrooke believes.

International opinion, it appears, agrees with him.

Last year's OECD report on wealth inequality recommends governments use inheritance taxes to tackle the problem.

"A key aspect of wealth accumulation is that it operates in a self-reinforcing way; wealth begets wealth," the report said.

"Overall, this means that, in the absence of taxation, wealth inequality will tend to increase."

An inheritance tax would do more to reduce wealth inequality than a capital gains tax, the OECD said.

Rashbrooke's favoured inheritance tax is a lifetime gift tax. The lifetime gift tax would kick in once a person had received gifts that totalled more than a set threshold.

"Above that limit, say $100,000, they would then be taxed on those gifts at a given rate."

He suggests the revenue from that tax be used to fund "a kids' KiwiSaver-type scheme" to help children in poor families.

"Recognising that their parents aren't going to be able to help, and that that is through no fault of the children, and that we as a society should help them build up their savings for a limited range of purposes such as buying a house or retirement savings.

"This would even-out the unfair advantage of luck. That's one of the things a fair society does."