Built in 1880, the terrace houses at 16-18 London St are visually stunning with their ornamental metal balconies and delicate iron-lace. The mansard-style roofs are unusual in Dunedin's architectural lexicon, as they look like they would be more at home in Paris than Edinburgh.

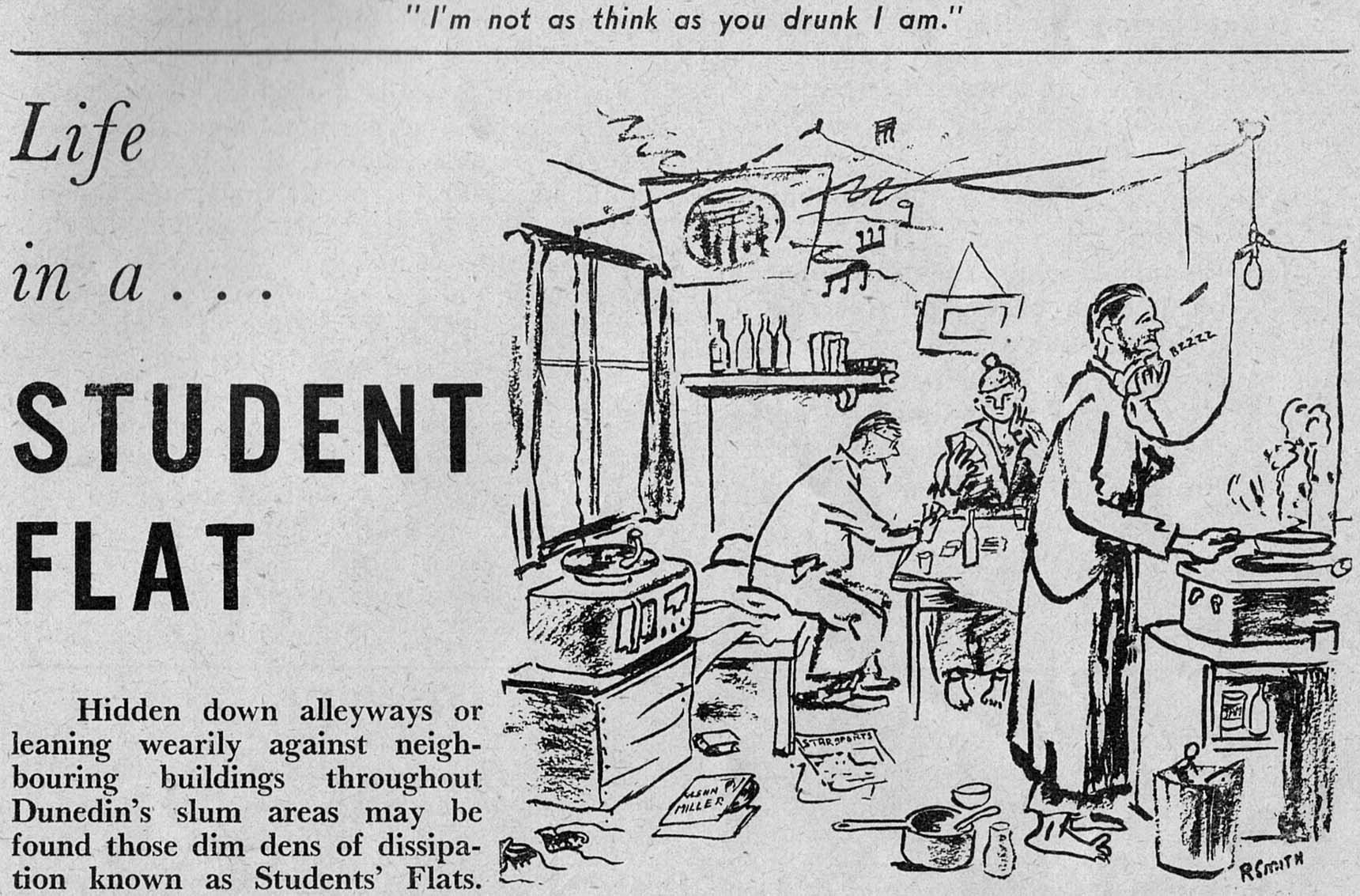

Students are known for living in some pretty dire accommodation and we know the names of their flats can reflect this fact. We see it in names like The Heap, The Swamp, Kelpfish, Permafrost and The Moist Box, all of which describe the state of the house. In this case, Skid Row has a bit more of a story to tell, which may reveal the origins of its name.

Brian Tidmarsh, retired associate professor of dentistry, lived at 18 London St in 1956 with his flatmates, a mixture of medical and dentistry students. Their flat shared a back boundary with The Royal Albert Hotel (latterly The Albert Arms, currently The Bog), which proved handy as bars were "supposed" to close at 6pm at the time.

While there is no clear memory of why the flat received its name, it is possible it may have been due to an unexpected housemate. An elderly woman known only as Mrs Hansen came with the flat. No-one remembers how long she had lived there, and Mrs Hansen didn't recall her age or precisely where in England she was born. She was both very deaf and illiterate, and the students supported her.

Brian recalls, "She just came with the flat, had her own room, paid no board, seldom spoke, cackled a lot, but kept the coal range going and always had the potatoes peeled and cooking by the time we got back from the pub. She was quite an asset and very proud of `her boys'. Today, I'm sure she would have been `in care' somewhere, but I'm equally sure that her life with `her boys' was what she wanted."

It was a curious situation and, apparently, Mrs Hansen would not be drawn into conversation. She owned very little, but her room was piled with newspapers.

Brian elaborated, "I think it was the pictures that she liked, but it was hard to tell as she steadfastly refused to enter into any sort of conversation. She could also swear pretty well ... I recall a tirade of abuse being hurled from the backyard where, one evening, she was chopping some kindling to light the stove for the following morning, and one of my flatmates lobbed an empty beer bottle out of his attic bedroom window, narrowly missing her!"

Mathews also covered nearly every wall in the house with caricatures and was popular at parties for his lengthy recitations. Brian remembers his "prodigious memory for the poetry of Robert Service, which he could recite for hours. In his cups, as he often was, he was impossible to shut up. The Shooting of Dan McGrew and Eskimo Nell were favourites."

After Brian and his flatmates graduated at the end of 1957, the flat was passed on to other students and Mrs Hansen was adopted into the care of another generation of students.

A few years later, from 1962 to 1963, Ross Smith was living in Skid Row and he recalls the reputation the house had prior to him moving in: "A Dunedin firm, Dirty Work Unlimited, was employed by the owner to clean up the flat after the student occupation of 1961. One of the cleaners is reputed to have said, `This is the filthiest mess we have ever handled!"'

In 1962, Dr Erich Geiringer boarded at Skid Row for six weeks. Dr Geiringer was a physician, a pro-abortion activist and the founder of the New Zealand Medical Association. After his death in 1995, The Independent described him as being responsible for dragging New Zealand medical practice into the modern world.

Ross has a particular memory of his sojourn at the flat: "On one occasion during his brief residence, he invited his friend and New Zealand author Barry Crump to stay for the night. The next day, the two men took up position outside the Royal Albert Hotel and proceeded to hand out pamphlets exhorting women to have a Pap smear for the prevention of cervical cancer."

This action was apparently not well received by the university, which several sources report found the initiative obscene and banned it by edict.

In his extensive bibliography of Barry Crump, Rowan Gibbs quotes a letter from Crump, which Erich published and responded to, reporting on the impact of their public health campaign: "In his periodical N.Z. Medical News 7 (29 May, 1963), Geiringer prints a brief letter from `Barry Crump, North Queensland': "Dear Erich ... Why don't you publish details and results to date of the cervical smear campaign we did in Dunedin last year?" Geiringer replies that the number of smears done in Dunedin rose by 153% ... "Figures on beer consumption in Dunedin during our stay are unfortunately not available. I hope to publish some of the interesting details of our campaign in a leaflet to the boys who helped us. Please leave a few crocodiles alive to help the medical profession weep for the women who still needlessly die of cancer of the cervix every year."

In the following decade, the 1970s, the terrace was known as The Spanish Slum. Jan Alexander remembers visiting her then boyfriend - later her husband - Ross, there and seeing the name stencilled on the door. The flat also had a letterhead.

A generation later, 16 London St became a Mexican restaurant called El Sol. The business signs can still be seen on the building, but it closed in mid-2009. While still bearing the evidence of its short life as a restaurant, the flat bore the name The Orifice. The sign was white board with cursive script in black, the large O containing the "Tongue and Lips" or "Hot Lips" logo that John Pasche created for The Rolling Stones - symbolic of "sex, defiance and Jagger's big mouth".

The book

Scarfie Flats of Dunedin, by Sarah Gallagher with Ian Chapman, published by Imagination Press, RRP$49.99