During the depths of an Otago winter, our heaters, puffer jackets and electric blankets keep us comfortable. How did staunch early Otago folk cope without these luxuries?

Southern Maori knew how to live off the land in all seasons. Plants provided the raw materials for building cosy houses, making waterproof raincoats, baking tasty bread, crafting musical instruments and even making fine perfume. Many plants were valued for more than one use.

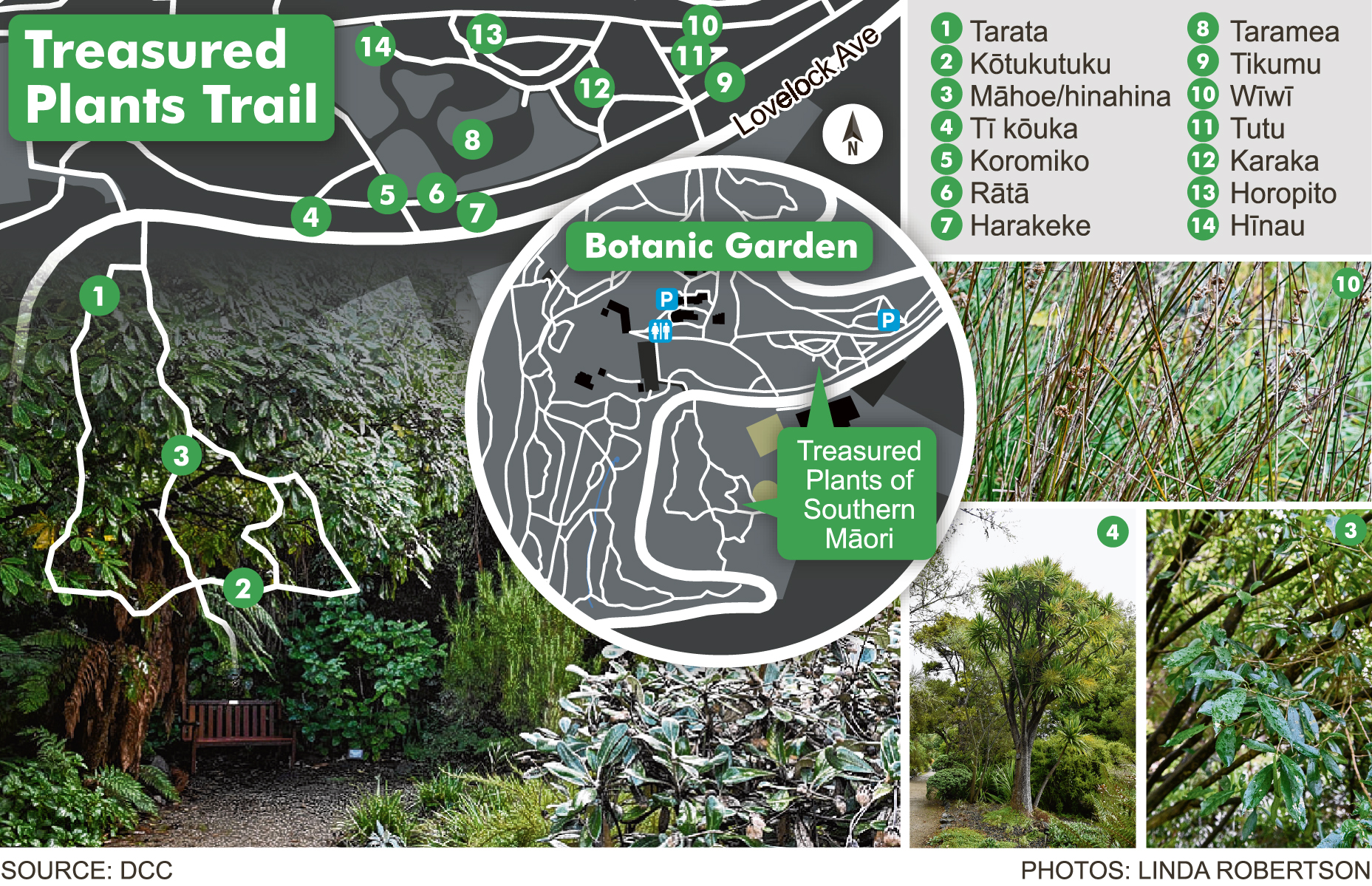

Fifty-five native plants have been recognised as so treasured that they are classified as taonga (treasured) species in the 1998 Ngai Tahu Claims Settlement Act. Many grow in the Dunedin Botanic Garden and have been gathered into a new treasured plants trail through the upper garden. The trail is based on stories in Treasures of Tane (Huia Publishers), Portobello journalist Rob Tipa's new book documenting traditional uses of the plants of Ngai Tahu.

You'd imagine that some of the most important plants must have been those that made fire. To do this, early Maori rubbed a hard stick on a slab of softer wood such as mahoe to form a groove. This contained flecks of mahoe which smouldered and were then fanned into a flame. People carried fire around with them by enclosing smouldering, slow-burning sticks of mahoe in a stone container.

Few plants were more valuable to Ngai Tahu than ti kouka (cabbage tree). It was a reliable vegetable and was used for weaving handy items such as sandals and rain capes. People dug out the tap root, roasted and pounded it to release the sugars, then mixed it with fish or bird fat for taste. Otago Peninsula was one of the best areas to harvest ti kouka.

Mountain daisies, Celmisia species, were also woven into waterproof raincoats, cloaks and hats. The classic harakeke or flax was a staple for weaving essentials such as clothes, mats, baskets and rope. When northern chiefs learnt from early Pakeha settlers that this versatile plant didn't grow in England, they were astonished people could live without it.

Another plant that protected against the southern climate was wiwi, various species of rushes. In the days before corrugated iron arrived on our shores, these species may have made all the difference between a dry whare (house) and a wet one. Thick layers of wiwi and other grassy plants made roofs and walls waterproof. Bundles of raupo (bulrush) were secured to a framework of poles with flax ties. The side walls received a second layer of raupo and sometimes another layer of wiwi. The roof structure was covered with a thick layer of wiwi to waterproof it, producing an effect no different from that on traditional thatched roofs still seen in Ireland.

How would we survive these days without the supermarket? In early days, bread was made from Elaeocarpus dentatus, a tree that grows throughout the North and South Islands but not Stewart Island. Hinau grows berries in autumn and winter used for bread so tasty an old Maori proverb says, "A hungry man should not be awoken from his rest unless it is to eat hinau bread.'' But the flesh of the berry is harsh and bitter and was rendered edible only by being soaked in water first, sometimes for months.

Karaka has a similar "don't try this at home'' reputation. Ripe fruit contain a lethal poison, but this tree was still one of the few cultivated by southern Maori. Nuts inside the orange fruit could be ground up to make bread but only with meticulous preparation to remove the toxin. Without being baked, trampled and soaked for days, karaka berries caused such horrific convulsions that a person could dislocate their neck.

Examples such as this make me marvel at the early people's skill in coming to a new country and figuring out how to safely use the new plants they encountered.

Tutu is similar. Despite most parts of the plant being poisonous, and its reputation for killing grazing cattle, early Maori knew how to make a refreshing drink from it, an edible jelly and a tasty sweetener. It was even used as indelible ink for tattooing the skin.

Our common tree fuchsia, kotukutuku, is more purely benign. It grows berries sweet and delicious to eat straight from the tree, easily the best fruit in the New Zealand bush. Before European contact, Maori had few sources of the colour blue, so girls coloured their lips with the blue pollen and youth of both sexes used it to decorate their faces.

For when the going got tough, horopito, or pepper tree, was nature's own painkiller. Its fresh, peppery leaves were chewed to treat toothache and headaches. Scientists have identified 29 compounds in horopito, including at least four active antifungals and powerful antioxidants.

Koromiko, commonly known as hebe, is a great medicinal plant, too. Various species were famous around the country for being a fast, reliable cure for stomach aches and diarrhoea. During World War 2, dried leaves were sent to New Zealand soldiers overseas as a remedy for dysentery.

But life isn't just about survival and early southern Maori knew how to use plants for the good times, too. Speargrass or taramea is a little toughie that will draw blood if you touch its tip. Despite this, it produces a sticky resin that mixes well with other oils to make a delightful, lasting scent. It could be hung around the neck, allowing the wearer to enjoy the pleasant perfume wafting up to their nostrils. Lemonwood gum also makes beautiful perfume and even a good, sticky glue.

Rata's hard, solid timber is good for carving pieces that need strength and works well for refined, intricately carved smaller pieces such as spinning tops and musical flutes.

- Clare Fraser is information services officer at the Dunedin Botanic Garden.

The trail

The Dunedin Botanic Garden’s new treasures plants trail will be launched on Saturday, June 29, with a tour led by knowledgeable guides from 1.30pm to 3pm.

Rua McCallum (Ngai Tahu) will focus on plants used for the manufacture of textiles.

Musician Alistair Fraser will compare live plants with their final form as traditional Maori musical instruments.

Author Rob Tipa will look at some of the treasured taonga plants used in daily life by early southern Maori.

The tour is free, but spaces are limited. Bookings can be made on 477-4000 or by emailing dcc@dcc.govt.nz