Yvette Williams won three gold medals at the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games; an outstanding feat.

But what makes it truly remarkable is that she competed in two of the events at the same time, Williams’ biographer Angela Walker says.

"Two of the gold medals were won simultaneously; the discus and the long jump," Walker, herself a Commonwealth Games gold medallist, explains.

"It illustrates just how successful she was across different disciplines. What she was capable of doing was really quite extraordinary."

Williams, who had won the Olympic Games women’s long jump gold medal two years previously, in Helsinki, Finland, was forced to compete in the two Vancouver events concurrently due to the untimely arrival of Queen Elizabeth’s husband Prince Philip.

"The events were unfortunately slated to take place on the same day. But then, the late arrival of the Duke of Edinburgh meant the long jump was delayed and they ended up being run simultaneously," Walker explains.

Competing in both events meant constantly alternating between opposite sides of the stadium’s athletics field, changing footwear and making the mental shift needed between each round of competition in two entirely different sporting disciplines.

"Yvette ended up having to cross the in-field from the long jump pit to the discus throwing circle 12 times while she did six throws and six jumps."

She won gold medals in both — adding them to the shot put gold she won on the opening day of the Games.

It is believed to be the only time an athlete, man or woman, in the modern era, has competed at an international level in two different disciplines at the same time and won gold in both.

But that day in Vancouver, Williams’ achievement was overshadowed by the men’s one mile race, in which Roger Bannister, of the United Kingdom, and John Landy, of Australia, became the first two runners to post sub-four minute miles in the same race.

"So, it is a little-known story; that she won these two Commonwealth gold medals simultaneously."

It is a vignette that parallels the broader story of Williams herself, who too often in the public consciousness in recent years has not been remembered for her achievements on and off the athletics field.

"There are biographies for all the other athletes of the golden age of athletics — Jack Lovelock, Peter Snell, Murray Halberg, John Walker — but curiously there wasn’t one for Yvette," Walker says.

Until now.

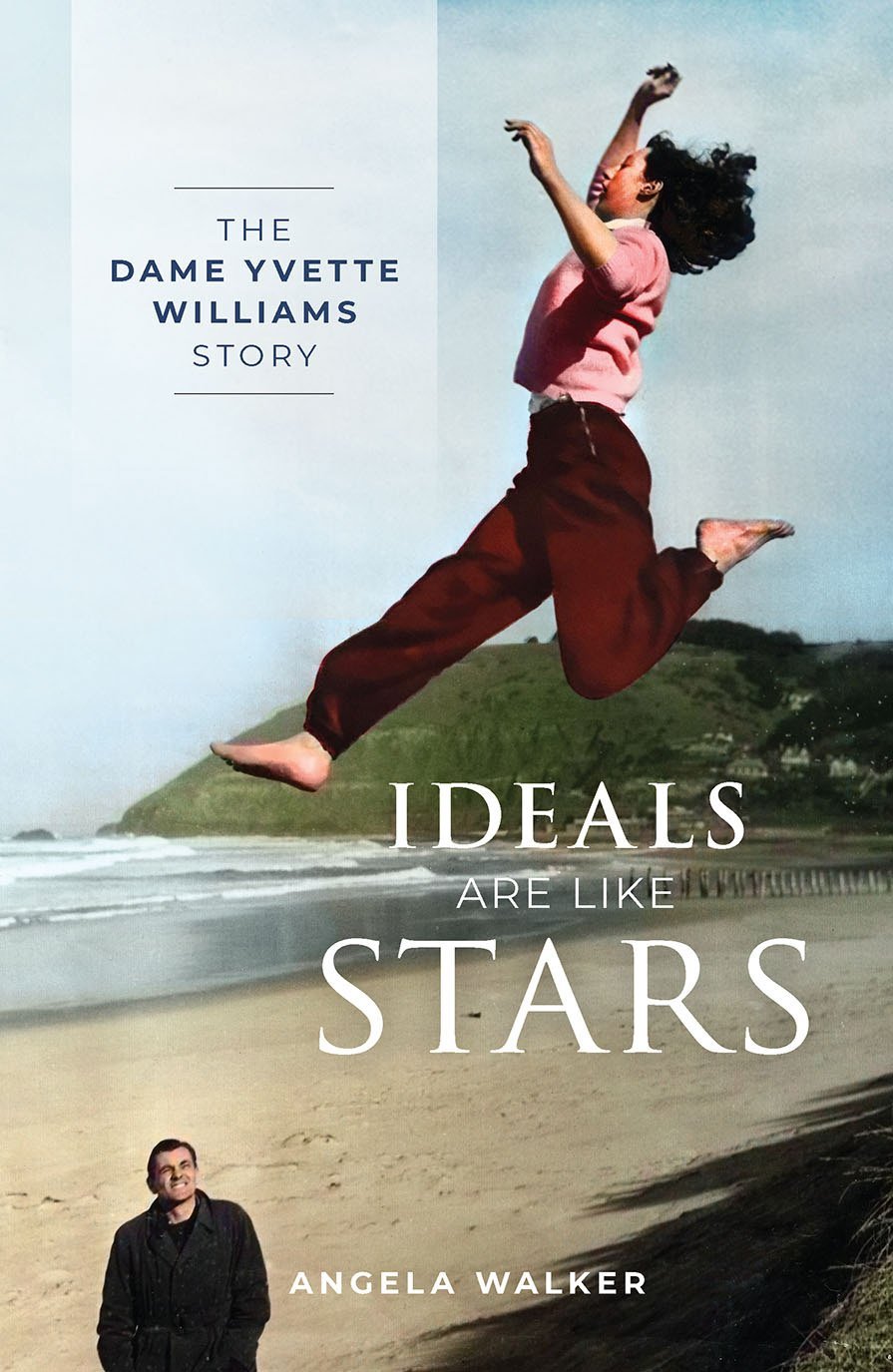

Ideals like Stars: The Dame Yvette Williams Story , in bookstores on Monday, tells the previously unpublished full story of the first New Zealand woman to win an Olympic gold medal.

Born in Dunedin, on April 25, 1929, Williams grew up in a loving, hardworking, Depression-era family whose home was on the slopes of Clyde Hill, overlooking Carisbrook rugby ground.

An active and adventurous child, she first gave athletics a go at the age of 17, at the invitation of a friend.

Williams quickly became a national champion — and then an international one.

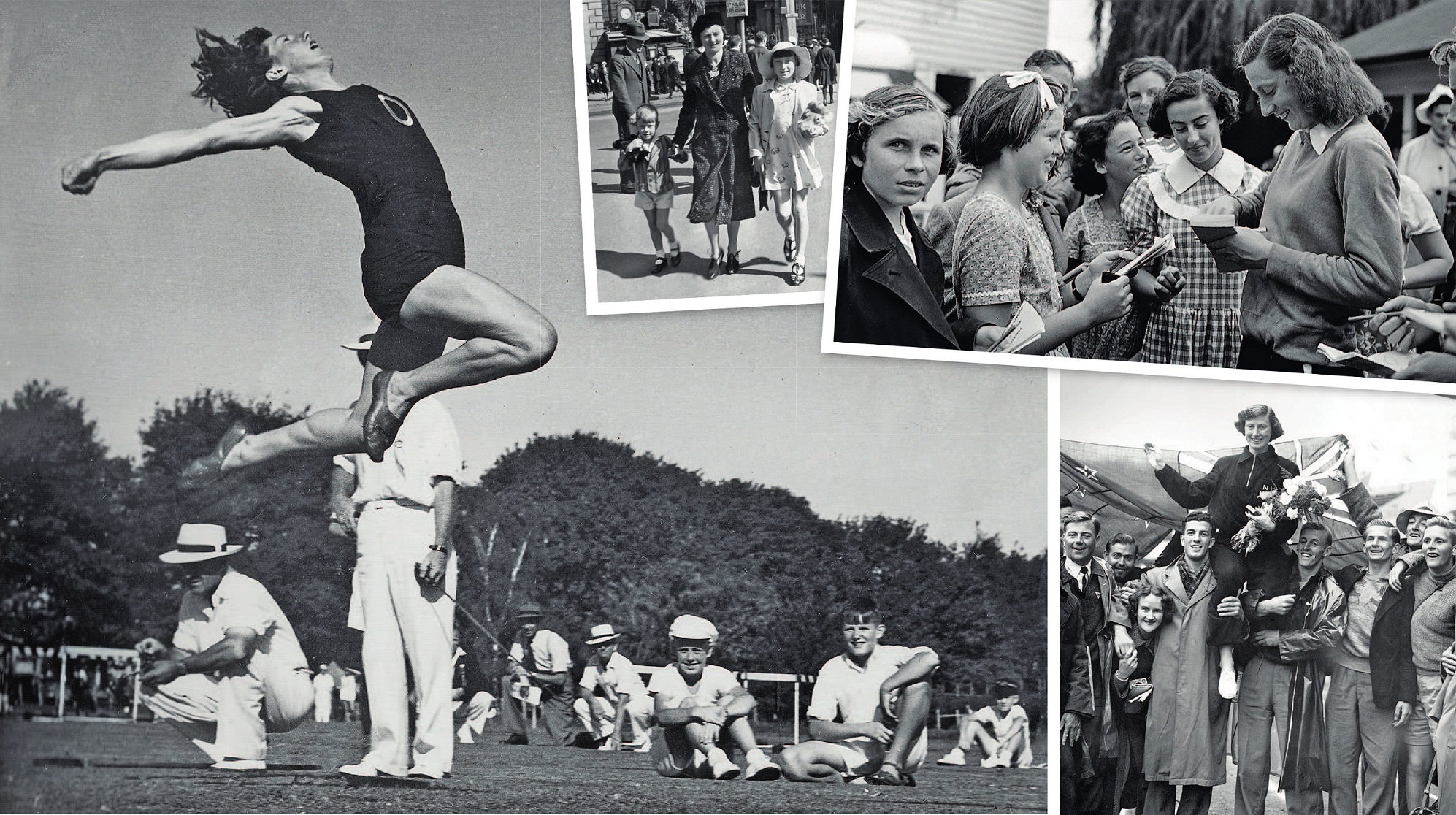

She won an Empire Games long jump gold medal, in Auckland, aged 21; was named Sportsman of the Year twice; and, in 1952, won the Olympic gold medal (in the same discipline), in Helsinki — a feat not repeated by a New Zealand woman for another 40 years.

Williams’ sporting excellence was not limited to long jump.

Between her start in athletics and her retirement from sports when she married, in 1954, Williams won 21 national titles across five disciplines; shot put, javelin, discus, 80m hurdles and long jump.

During those seven short years, she won four gold medals and one silver medal at Empire Games and one Olympic Games gold medal. In 1954, she also broke the women’s long jump world record.

To reach such heights, Williams had to go against the norms of the day, blazing a trail through 1950s New Zealand for future female athletes and many others to follow, her biographer says.

It is a "chronicle of one humble woman’s quest for excellence through hard work and sheer determination".

The effort required to reach the international stage is something Walker knows from personal experience. At the age of 21, she represented New Zealand in the rhythmic gymnastics all-round competition at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea. Two years later, she won a gold medal and three bronze medals at the 1990 Commonwealth Games, in Auckland.

Long-standing connections with Williams — Walker knew her daughter Karen who was a representative gymnast and Walker was coached by Williams’ former coach Emmy Bellwood — made writing her biography almost inevitable, although still serendipitous to Walker.

"Yvette read my first book and really loved it, apparently," Walker says.

"It wasn’t long after Yvette died that Karen reached out to me."

Unknown to Williams’ daughter, Walker had already been thinking that writing the pioneering athlete’s biography would be a dream job.

"It was a great thrill. It was unbelievable that they were asking me to do what I had actually been wishing I could do."

The huge boon for Walker, as she began to research Williams’ life, was being given the athlete’s never-before-seen personal diaries.

"Within weeks, I met with Karen. At that point I didn’t have any idea how rich a personal archive there was to tap in to."

Williams’ daughter was able to hand Walker a plethora of personal daily diaries and meticulously compiled scrapbooks.

"Quite bravely, they were prepared to entrust them to me, which was extraordinary."

Walker found herself swimming in personal archival material detailing every aspect of Williams’ meteoric sporting career.

A key moment on Williams’ path to success was the arrival of sports coaches Emmy and Jim Bellwood.

She met Mr and Mrs Bellwood, as Williams’ always referred to them in her diaries, during the inaugural nine-day National Athletics School, in Timaru, at the end of 1947.

The swarthy Mr Bellwood had studied at Britain’s leading physical education school and had recently returned to New Zealand with his new wife, a lithe-looking physical education specialist from Estonia.

When Mrs Bellwood watched Williams doing shot put — a discipline in which the 18-year-old had won a national competition earlier that year — the coach’s accented comment was "Not vedy far", Williams recorded in her diary.

Mrs Bellwood then demonstrated the correct putting technique and assured Williams that if she mastered it she would break her own national record.

The Bellwoods moved to Dunedin and became Williams’ coaches, employing training methods unknown in New Zealand. That included teaching Williams the hitch-kick long jump technique made famous by African American gold medallist Jesse Owens, at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Williams was the first female athlete, worldwide, to use the technique.

Williams’ world-beating achievements were due to her phenomenal natural talent, amazing competitive temperament and deeply disciplined effort. But, Walker says, without the Bellwoods’ knowledge and expertise Williams’ story would have been quite different.

"Yvette’s on record saying she would never have achieved what she did without them.

"Under their tutelage she moves from being the best in New Zealand to the best in the world."

With success came fame. Two years before her Olympic win Williams was named Sportsman of the Year for the first of two times, becoming a household name and a recognisable face nationwide as well as in her home town.

By then she was dating a young man, Charlie Bower, whom she had met at a Dunedin Town Hall dance.

In October 1951, they got engaged. Doing that quietly was difficult for someone as well known as Williams. Her diary records her and Bower abandoning their first attempt to enter J.C. Gore Jewellers, in Princes St, unnoticed to buy an engagement ring, but managing it on the second try.

The relationship, however, was constantly dogged by a clash of expectations and dreams.

Williams’ aspirations were unorthodox for a young woman of that era.

"All her friends were getting married and having babies. And her own boyfriend wanted her to do the same," Walker says.

"Yvette wrote in her diary, ‘One year today is the opening of the Olympic Games in Helsinki, so I just wonder if I’ll be there. Either that or doing housework I suppose’."

"Secondly ... but one which seems to always be a barrier between Charlie and myself is my athletic career."

In addition to the diaries, Williams’ family made available recorded oral histories voiced by the athlete and a recording of a comprehensive interview with Williams by children’s book author David Riley.

The challenge for Walker was how to distil so much information and then how to present it.

She chose a creative non-fiction style of writing; describing the sights, sounds, thoughts and emotions that Williams was experiencing as events unfolded.

It is a style of writing Walker herself enjoys reading.

"Where you feel almost like you are reading a novel, but it’s a true story."

But creating such a piece of writing, and it still remaining a non-fiction work, was only possible for Walker because there was so much of Williams’ diarised and chronicled information to draw on.

"I’m not interested in making anything up ... I was very much working with true information ... I had more detail than I could possibly use."

It has allowed Walker to breathe vivid life into crucial moments in Williams’ life, such as the jump that gave her the Olympic gold medal.

She could feel her legs kicking through the air, her chest lifting, arms swinging gracefully behind, taking her to the peak of the arc ... her feet moving together, reaching out for the furthest possible point, the grains of sand breaking apart, the six-metre mark trailing behind, her body falling forward ...

Gasps turned to cheers ... 6.24 metres the board declared — a new Olympic record. The screaming raised a notch.

For a few moments, Yvette couldn’t believe her eyes.

She stood there, blinking, unable to take it in.

Then it registered. She jumped up and down, her fists clenched, a wide grin spanning her face. It was impossible to fully express the overwhelming sense of joy flooding through her ...

Her mates in the team — Dutch Holland, Moss Marshall, Jean Stewart, Harold Cleghorn and George Hoskins — moved into formation and broke into a supercharged haka.

Back in New Zealand, her family, sports enthusiasts and news media followed the competition through the night. In the morning, the whole country celebrated her win, as Williams’ father told her in a letter.

"I decided after coming home from work on Wednesday to stay up all night," her father wrote.

"Russell Oaten [sports broadcaster at 4ZB], his wife, [Otago Daily Times sports reporter] Teddy Isaacs, two Times reporters and Charlie stayed all through the night with me ...

"At about quarter to six the final result came through, saying that you had won. Well that was the start of a day never to be forgotten in Dunedin ...

"Our old telephone rang continually all that day and night ... Telegrams started coming in, right from [Prime Minister] Sid Holland down to people who were complete strangers."

During the summer of 1953-54, Williams met Charles "Buddy" Corlett, a New Zealand basketball and softball representative. After the successful August 1954, Vancouver Games they announced their engagement and Williams announced her retirement from sports.

"She married, had four children and was a dedicated home-maker," Walker says.

Later, she became a physical education teacher and, befitting an Olympic icon, had a variety of sporting roles.

Williams died three years ago, on April 13.

She had no regrets about retiring from competition, Walker says.

"There wasn’t really anything much left for her to achieve."

As well as what she accomplished for herself, Williams did a lot for New Zealand women, and men, Walker says.

"Her sporting achievement really led to the impact she had on society — blazing a trail for sportswomen, showing what was possible.

"In the wake of that, there were more women taking up sport, more women being taken seriously [in sport]."

Walker quotes Olympic athlete and gym owner Les Mills, who spoke at Williams’ funeral, "Yvette to me was a beacon. She led the way for so many sports men and women ... She was proof that almost anything was possible."