In 2022, an article was published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Science in America, entitled "The biocultural origins and dispersal of domestic chickens". It involved 600 archaeological sites in 89 countries, and centred on where this bird was first domesticated.

To my astonishment and with a tinge of pride, I read I was responsible for discovering the earliest domestic chicken known. It was at a prehistoric village in Thailand called Ban Non Wat. Having excavated down about 4m, through hundreds of Iron and Bronze Age human burials, we encountered occupation layers dating to the first farmers to reach this part of the world after their migrations south from central China. It was in their rubbish tip, dating back about 3700 years, we found domestic chicken bones. Those farmers brought with them their rice, and they cut out their fields from the forests that surrounded their village.

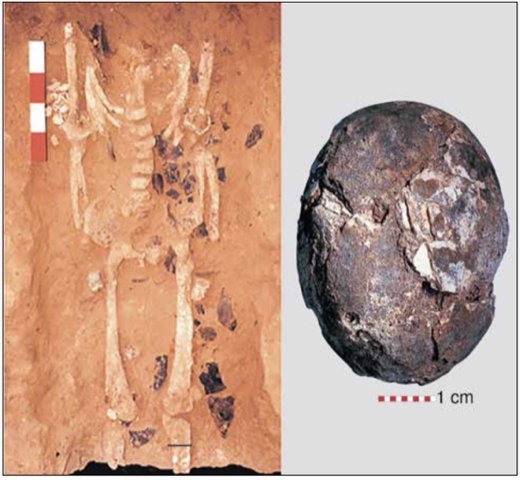

I mentioned the many graves we found at this site. One contained the remains of an elite Bronze Age man, buried with 35 superb pottery vessels, 20 shell bangles, thousands of shell beads, bronze axes and chisels, and — the complete skeleton of a domestic chicken. So these birds were being used in mortuary rituals.

A later grave at a nearby site, contained the skeleton of an 11-year-old, holding a complete hen’s egg. What better way to symbolise a new life after death than with an egg? It seems those remote prehistoric people were just as concerned about eternity as your Christian is today.