It was mid-morning, on a sunny Saturday, in North Dunedin, when Jacob (not his real name) took his first MDMA cap of the day.

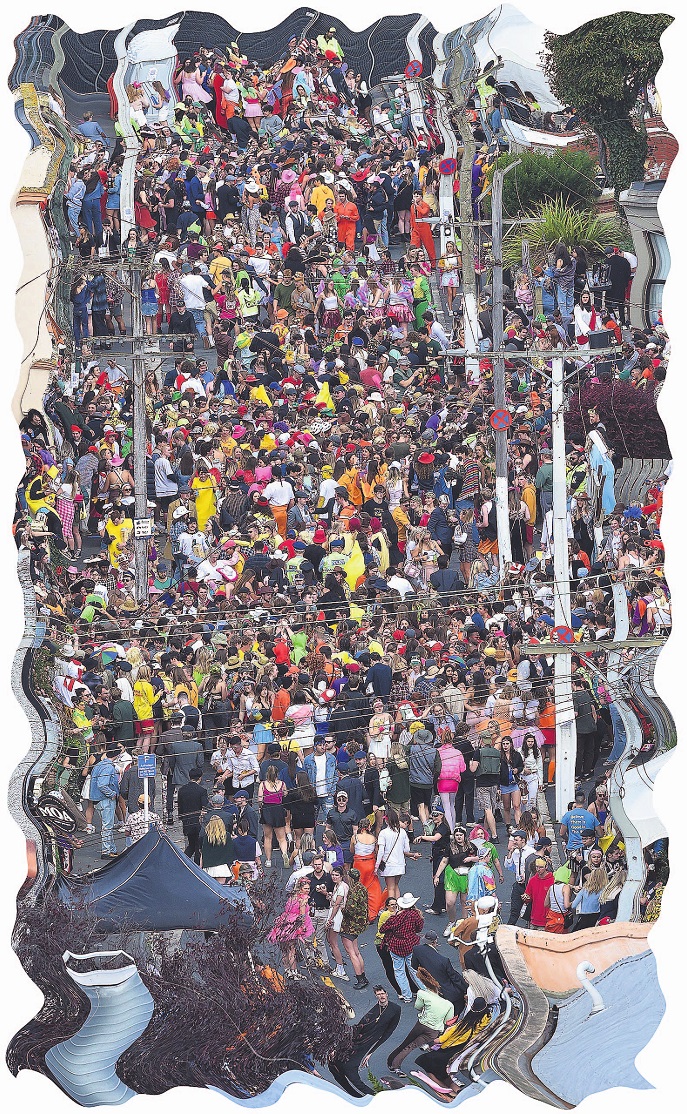

The 20-year-old student was dressed as a policeman. He had been drinking since 7am; keeping company with a flight of "pilots" as they limbered up for what promised to be a big day - the annual Hyde St party.

The sights and sounds of 3600 young people - dressed as everything from bananas to cowboys, and crammed into one street of flats - swirled around Jacob as he swallowed 0.1g of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA).

First comes the excitement of knowing what you have just done, he recalls.

"Then you just get more excited. You’re open to talking to new people. You’re more open to anything."

All would go well for Jacob that May day, for at least a few more hours.

Almost 80% of New Zealanders take drugs, if you include alcohol and tobacco. Of illegal drugs, cannabis has the highest use. About 15% of Kiwis used cannabis in the past year; nearly twice as many as a decade ago, according to the latest New Zealand Health Survey. Illegal use of amphetamines (mostly meth, a.k.a. "P") sits steady on 1.2%, or the equivalent of 16.7kg of meth being consumed nationwide each week. Weekly MDMA consumption is half that of meth, about 8.5kg, according to Police wastewater drug testing. The nation’s average weekly total cocaine consumption is 700g, worth about $200,000.

Wastewater testing shows people use drugs in every community in Aotearoa. But there are regional and socio-economic variations. Cocaine and MDMA tend to be middle-class and affluent party drugs, whereas meth use correlates with areas of greater poverty.

Nationally, Tamaki Makaurau, Auckland, consumes the most cocaine per capita; meth use is highest in Northland; and, Otago-Southland has both the highest MDMA use and the lowest meth use.

Across the Southern region’s four wastewater testing sites, Queenstown shows the highest proportion of cocaine consumption; Tahuna, Dunedin, shows the most MDMA use; and, Invercargill leads on meth.

People are using, but there are penalties for getting caught.

Possession of a Class C drug such as cannabis seeds or plants can result in three months in prison and a $500 fine. Manufacturing a Class B drug such as cannabis oil, opium or ecstasy can get you up to 14 years inside. The maximum penalty for a conviction for supplying the Class A drugs meth, magic mushrooms, cocaine, heroin or LSD is life imprisonment.

That is just the way it has always been, right?

Well, no.

Although there is a deplorable centuries-old track record of countries banning drugs simply because they were "foreign" - coffee, for example, was at one time banned in Mecca, Italy, Constantinople, Prussia and Sweden - our most-widespread, Western approach to drugs is only half a century old. And ill founded.

"It became a near all-out war," Dr Ward, a University of Otago psychologist who teaches neurobiology, the behavioural effects of drugs and New Zealand drug policy, says.

Because of its superpower status, the US was able to influence drug policies in other countries.

In 1975, the New Zealand Misuse of Drugs Act came into force. Amended, it is the drug law Aotearoa still operates under.

But Nixon’s war on drugs, picked up and accelerated in the 1980s by US president Ronald Reagan, has been shown to have been almost entirely duplicitous.

Nixon’s senior adviser John Ehrlichman has admitted, "The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the anti-war left and black people".

"By getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalising both heavily, we could disrupt those communities," Ehrlichman said.

"We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings and vilify them night after night on the evening news.

"Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did."

This is not an article claiming all drugs are harmless. Despite the Ministry of Health finding that four out of five New Zealand adults using illicit drugs report no harmful effects, for a small group, drug-use causes significant harm, sometimes to themselves, sometimes to others. In fact, the New Zealand Illicit Drug Harm Index estimates $1.9 billion of illicit drug-related harm occurs each year.

Those living in the poorest suburbs are more likely to experience harm from their own drug use. They are also most likely to want help with their drug use but not receive it, the New Zealand Drug Foundation says.

What might surprise, however, is which drugs, based on objective evidence, are most harmful, and which are least.

Top of the list, alcohol.

One-in-five New Zealanders 15 years or older drink hazardously, an estimated 825,000 people. Alcohol kills as many people each year (206 in 2018) as opioids, benzodiazepines and amphetamines combined (207). The country’s alcohol-related harm costs are disputed but have been estimated as high as $7.8 billion per year, four times as high as the combined harm cost of illicit drugs.

One of the least harmful drugs, LSD.

Taking LSD can produce "some pretty intense effects" and it can exacerbate pre-existing psychiatric diseases such as psychosis or schizophrenia.

But outside of that, Dr Ward says, "LSD is actually one of the safest drugs out there. You can take a whole bunch of it and you wouldn’t overdose".

In fact, he says, researchers are getting pretty excited about psychedelic drugs, including LSD and magic mushrooms, as well as other drugs such as MDMA (to aid talk therapies) and cannabis (for chronic pain).

"Researchers are finding, because of the way psychedelics expand your perception and loosen rigidly held worldviews ... that it can be very beneficial therapeutically."

Trauma therapy is one of the most promising areas.

The not-what-we-expected relative harms of alcohol and LSD point to one of the big problems with the War on Drugs. It is based on prejudiced opinion, not objective evidence.

"There are a lot of people who have strong anti-drug opinions," Dr Ward, who does not use drugs but would if he felt the need, says.

For example, the drug classification regime setting out criminal penalties - which makes LSD a Class A drug worthy of life imprisonment - is not supported by the data.

"A new way of ranking drugs based on harm would be good," he says.

The War on Drugs has not reduced drug use nor drug dependence. Instead, it is swallowing an enormous amount of money and giving many people stigmatising criminal records, the Drug Foundation says.

The Government spends about $350 million each year tackling drugs. Most of it is spent on enforcement, rather than treatment.

Each year, hundreds of young New Zealanders are caught up in the youth justice system for drug offences. In 2019, there were 913 drug-related referrals for people aged 17 or younger. Almost 90% were for cannabis possession or use.

The Drug Foundation says that for most young people, the harm of being brought into the criminal justice system far outweighs the harms of experimenting with cannabis.

New Zealand has taken some positive steps, although not all of them have come to fruition. Here are four.

In 2013, the country passed a world-leading piece of legislation setting up a health-focused framework for the testing, manufacture and sale of psychoactive substances. But an addition to the law, stipulating drugs could not be tested on animals to prove their safety, essentially rendered it unworkable.

In 2020, it became easier for doctors to prescribe medicinal cannabis. But a referendum the same year, which could have legalised the regulated possession and sale of cannabis, was a step too far for 50.7% of the public.

Lastly, in April this year, New Zealand became the first country to make it legal to offer safety testing for recreational drugs.

New Zealand has always had a unique drug scene, in part because it is so far from everywhere else. Comparatively high levels of cannabis use and being the birthplace of legal highs are two markers of that home-grown, down-under approach.

But as long as the War on Drugs continues to be the bedrock of New Zealand drug policy, the country’s far-flung location is actually making harms worse.

In recent years, the price of more exotic drugs has skyrocketed here. This has brought the country to the attention of international drug cartels. The cartels have formed partnerships with local gangs to distribute and sell the imported drugs.

"New Zealand has become very attractive because of the high retail price," Detective Superintendent Greg Williams, director of the National Organised Crime Group, confirms.

Det Supt Williams cites a 600kg meth bust at Auckland Airport, in February. Drugs that would have cost the cartel $5 million, could have wholesaled for $122 million and retailed for double that.

During the past six years, the Police crime group, working closely with New Zealand Customs and overseas agencies, has identified and disrupted 24 transnational crime cells, Williams says.

The recent case of 91kg of cocaine being detected on a ship overseas destined for Port Chalmers, was "a classic example", he said.

For every bust, it is likely many shipments go undetected.

The illegal drug trade is proving alluring and deadly. During the past five years, New Zealand has had a 50% increase in gang members and a 21% increase in violent crime.

When it comes to drugs, then, what is the country’s end-goal?

If it is evidence-based harm minimisation, is the current approach fit for purpose?

"No", says Dr Ward, the Drug Foundation and a growing number of other voices.

A paradigm switch is long-overdue, they say.

"If what you’re really trying to do is reduce the harms of drugs, then having them be illegal and devoting a whole bunch of money towards the criminal-justice side of drugs, it doesn’t work," Dr Ward says.

As a working alternative, he points to Portugal where, in 2011, the country decriminalised all drugs.

"Instead of arresting people and prosecuting them for possession, they divert them into treatment and other types of support."

A more radical step than decriminalising drugs would be to legalise them.

"You could heavily regulate their production and distribution. And you could tax them. It would be a source of revenue for ... harm reduction, education and treatment."

The success of any new approach would rely not just on changing the legal standing of drugs but on also moving the money from enforcement to health.

Jacob’s health took a turn for the worse towards the end of the Hyde St party.

He popped a second cap of MDMA at about 4pm - and lost the next two hours.

His friends tell him he was still fully conscious. They’ve described to him the things he got up to. But he remembers nothing until wondering how he got to a flat on the other side of the campus.

Hyde St was only the second time Jacob had taken MDMA.

He now uses it every few weeks.

Apart from blacking out at Hyde St, and another time when he thinks the MDMA was cut with ketamine - "I had regrets from that. I was all over the show" - he has enjoyed the experiences of enhanced sociability.

The "come downs", however, are getting worse, he admits.

"The day after [using], I’ll feel OK. But the next days after that, say Monday through Thursday, can be pretty rough ... it’s hard to get out of bed."

He has no plans to seek health advice - it is an illegal drug after all - nor to stop.

"I love a good night out, so, it’s worth it."