In the days before lockdown, Otago Daily Times editorial cartoonist Shaun Yeo captured the prevailing mood with a few deftly executed lines and a little wash.

On the Tuesday, after Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern had announced the nation was headed for Level 4, an oversized padlock was plunged through a solemn grey South Island — fastened with a heart-shaped key.

On the Wednesday there was a heartfelt handwritten message on an empty classroom whiteboard, a sepia scene evoking simpler, happier times.

But then on that first day of lockdown, when another Covid-19 related cartoon might have been most expected, Yeo did something else.

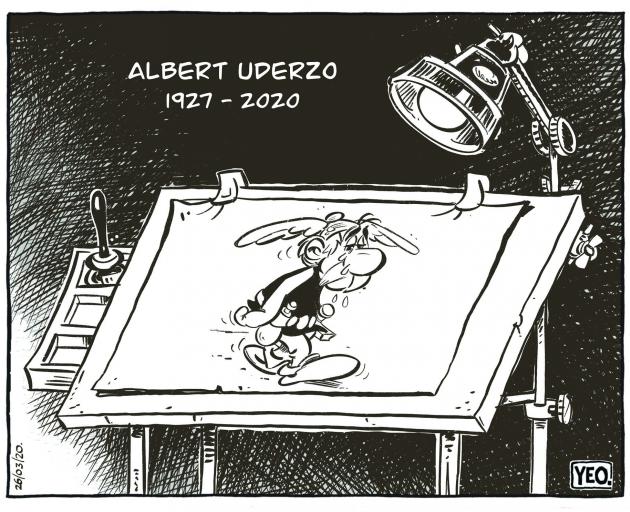

Below the editorial, in the hand-drawn rectangle among the letters, Asterix wept. Because Albert Uderzo was dead. The Frenchman who had delighted generations with his comic art, detailing the adventures of one small village of indomitable Gauls, had died the day before. Yeo (46) was grieving.

"That was a little bit self indulgent on my part," he says.

The other two were New Zealander Murray Ball, of Footrot Flats fame, and Herge, the Belgian behind the Tintin cartoons.

It was back then as an Asterix fan, in his early teens, that the Winton-born, Invercargill-raised boy asked his father if he might be bought a drawing desk.

"We can do better than that," his father said, and built a table himself.

Yeo uses it still. He did once try to move on to something grander, a more professional looking set-up, but it didn’t feel right.

"It’s beautiful, I love it," he says.

"It has a lot of memories. I have spent a lot of time sitting at that desk."

Over the years Yeo has produced galleries of work on that wooden surface, ranging from graphic design, to book illustration, advertising artwork and, of course, cartoons of all shapes and sizes. Now, on an almost daily basis, that includes the quintessential newspaper set piece, an editorial cartoon.

So, Uderzo’s passing had to be acknowledged, Yeo says, though also: "I can’t believe I did that".

"Knowing now what transpired ... Covid, the lockdown ..."

There was, it transpired, plenty of time for more Covid-19 cartoons. In fact, between mid March and mid May, Yeo hardly strayed from the topic — pretty much right through to May 20, when he served up a stricken Simon Bridges circled by sharks.

"Over those two months I had programmed myself to be thinking Covid cartoons the whole time," he says. "That shark one was actually a turning point because I was like, ‘there are actually other things going on now Shaun, you need to start moving away’."

However, he was "still sort of finding my feet as a daily cartoonist" when suddenly there was just one topic in town.

"If I could make people smile, or lighten the load a little bit, I took that as a huge responsibility."

Not that there weren’t more sombre moments. When the first person died from Covid-19, in Greymouth, Yeo drew another grey New Zealand, with a large cross standing on the West Coast.

"There wasn’t a cartoon that I did in that period, that I didn’t second guess," he says.

The pencil line must walk a fine line. There were to be no laughs just for the sake of a laugh.

"I’ve come up with a mantra to myself: you’re only as good as your last cartoon."

And Yeo sounds like a pretty tough crowd to please.

He says that once he’s sent his cartoon off — and assuming it’s accepted — he spends the next couple of hours taking another very critical look at it, thinking about what he could have done better.

"My wife is constantly telling me, around the dinner table, ‘You have to let it go’."

He launches into the sort of self-directed dissection with which those in the Yeo household must be familiar. It’s pretty searching.

On the upside, he says, if he thinks he’s filed a sub-par cartoon one day, that’s further motivation the next.

As much as he can, he tries to start each day with a clean slate.

"There are a few things you’d like to comment on and there are a couple of ideas that are floating around that you think you could address. But I try to sit down each day and start from scratch, so I don’t get too far ahead of myself," he says of his process.

"She’s an interesting beast, all right."

"I’d love a studio," he says, "surrounded by all my books and art and all of that sort of stuff but at the moment I am just tucked in a corner of the house."

There’s a documentary coming in next month’s online Doc Edge Film Festival about New Yorker cartoonist James Stevenson. In it, one of his editors talks about the sleight of hand involved in the cartoonist’s craft: "As with every good cartoonist, it looks effortless, but it only looks that way because he’s put a lot of effort into it."

Yeo’s work certainly ticks that box. One of his Covid-19 cartoons involved a well-rounded middle-aged gent standing in the window of his house, wearing a teddy — a short woman’s nightgown. It’s a sight gag playing on the Covid-19 custom of putting a teddy bear in the window to amuse passing children. In the cartoon, the wife’s face is a brilliant mix of appalled and fed up as she tells him he has it all wrong, again.

Yeo nominates it as one of his favourites from the period. But it’s far from the piece of dashed-off slapstick readers might assume.

"I left that for a couple of days, that one. Because I was like, ‘am I just taking the [mickey]’. I had a rough sketch and my wife was a great sounding board over that period because she was locked down with me ... She saw it on my desk and was like ‘That’s a cracker’."

Then when it appeared in the paper it actually gave Yeo himself a chuckle.

Another of the more broadly humoured sketches from the period is, Yeo says, is a favourite for another reason. It shows a man newly returned to work at the office, sitting dishevelled at his terminal in undies and singlet. His boss is only just holding it together.

What must be remembered is that while the content of these pieces of work is important — the cutting edge, the pin sharp barb or observation — so is the art itself.

New Zealand cartoonist Tom Scott — the man whose cartoons of former Prime Minister Robert Muldoon needled him close to apoplexy at times — noted that editorial cartoons are often the last hand-drawn part of a newspaper left.

"That’s my best drawn cartoon, I think, I’ve done," Yeo says of the back to work piece.

"Most people wouldn’t recognise that but I really like the mannerisms of the characters and the fact he’s playing solitaire on his computer."

The joke itself is a little on the weak side, he says, which can result in an overdrawn cartoon, but here the balance was just right.

"I love the craft," he says.

"I have adored the artform for pretty much my entire life.

"I strive to draw well."

There’s been a trend in political cartooning for the message to be all-important, the artwork less so, which Yeo questions.

"Energy" is a watchword he mutters away about to himself. It’s what he tries to capture and it’s often there in an initial sketch, free and loose. The trick is to hang on to it. An overdrawn piece can end up stiff and lifeless, perfection the enemy.

"Sometimes I’ll draw something and I’ll purposely go back and rough it up."

On other occasions it all clicks and flows and the lines simply fall into place.

That happened one day in March last year, following the Christchurch mosque shootings, resulting in the "Crying Kiwi" cartoon that captured the imagination of millions around the globe.

"There really wasn’t a lot of thought going into that at all. It was just emotion."

Yeo says he’s very proud it resonated with people, because it came from an honest place.

"When you do something like that, and you’re not doing it for kicks, you’re not doing it for hits online, that’s just what you do, you just felt you had to do something, that’s a really lovely thing."

The process of drawing is not always a conscious process, he says, with the brain sending a detailed set of step-by-step instructions to the hand.

"That was one of those drawings where I just drew and it was a blur."

Then the critic walks back into the room.

If he’d known the Crying Kiwi was going to go quite as nuts as it did, he’d have spent a little more time on it, he says.

Fellow New Zealand cartoonist Toby Morris has said he once feared each person was allocated an ideas jar, which once emptied remained so.

And indeed James Stevenson, in the documentary, talks about his early experience with The New Yorker when he was employed to write the gags for artists who had apparently exhausted their own repositories.

"You just hope that the idea jar never empties," Yeo says.

"Some days you panic because, you think ‘I’m buggered’. I am just going to email the editorial team and that’s it, I’m done, I have nothing."

That’s despite the ideas part of the brain remaining in a constant state of alert, he says; dialled into the news, tuned in to conversation, observing the queue at the supermarket and wondering what everyone is thinking, filing things away.

Even then, sometimes he has to sit down at the desk, pick up a pencil and just start drawing ... something. It still all starts with pad and pencil.

Routine can be important.

That was reordered somewhat during lockdown, when his quiet home workspace became filled with the rest of the family, who gained new insight into his work practices.

"My son said, ‘There’s a lot of lying on the couch staring at the ceiling, Dad’. I said, ‘I’m still working here, mate’."

It’s politics next, an election looming.

And the well exercised critic appears to be hard at work, as Yeo volunteers that he’s not sure he was as even handed during the last one as he might have been — an equal opportunity bludgeon.

"I would really like to sit in the middle," he says.

It’s not fair if you have the privilege of prime newspaper real estate each day, to be laying into one side repeatedly.

"You have to stand for something, but I just want to be a little bit more down the middle."

That may change, he says, if one side is simply too irritating.

Which brings us to the Prime Minister. She’s tricky, he says, because she’s really quite nice: "Hard to go after because she comes from a genuine place. Some of the politicians don’t, they’re quite easy canon fodder."

Other work bubbles along. Yeo also illustrates children’s books.

Daily cartooning is usually over by about 3.30pm, after which he takes an hour off. Then, after tea he gravitates back to the drawing desk and the children’s books.

"Which I absolutely adore," he says.

"That’s a wonderful thing to do after doing a political cartoon or a topical cartoon, you are switching from reality into a fantasy world. It’s just nice."

Then tomorrow he’ll be back at that old desk, in the corner of the sunroom, with another observation on the world as it passes.