You might well have heard this one before, but bear with: Otago has way too much nitrogen washing into its water ways.

A recent report by the National Science Challenge Our Land and Water, Toitū te Whenua, Toiora te Wai found the province needs to reduce nitrogen loads by a third. And cut back on E. coli — poo, there’s too much poo in the water.

The sheer quantity of the pollution means achieving water quality goals will be "extremely challenging", the researchers say in typical scientist understatement.

In other words, we’re demanding more of the environment than it can cope with.

It’s science.

But also economics, in as much as all this pollution is a byproduct of our little South Pacific nation’s efforts to get about its business and make a living.

Which is another thing. It’s clear that our efforts to make a living, to get by, aren’t getting everyone across the line.

Deficits are everywhere, homelessness is epidemic, foodbanks are doing a roaring trade, loneliness is rife.

We’re not alone in this, the COP28 meeting in Dubai is evidence of that — record high CO2 pollution alongside a lengthening bill for the cost of its impacts on people.

It’s reality check time, we need to do a better job for people and the planet.

Enter the stodgy confectionery.

Among the responses to these twin challenges — looking after both people and the planet — and one now being investigated by the Dunedin City Council, is a doughnut. Neither cream nor chocolate, this is doughnut economics, as framed by Oxford University economist Kate Raworth, and the city was recently presented with its own first draft doughnut, or City Portrait — which, yes, identified nitrogen as among the problem areas. And phosphorus. Waste was another. And CO2.

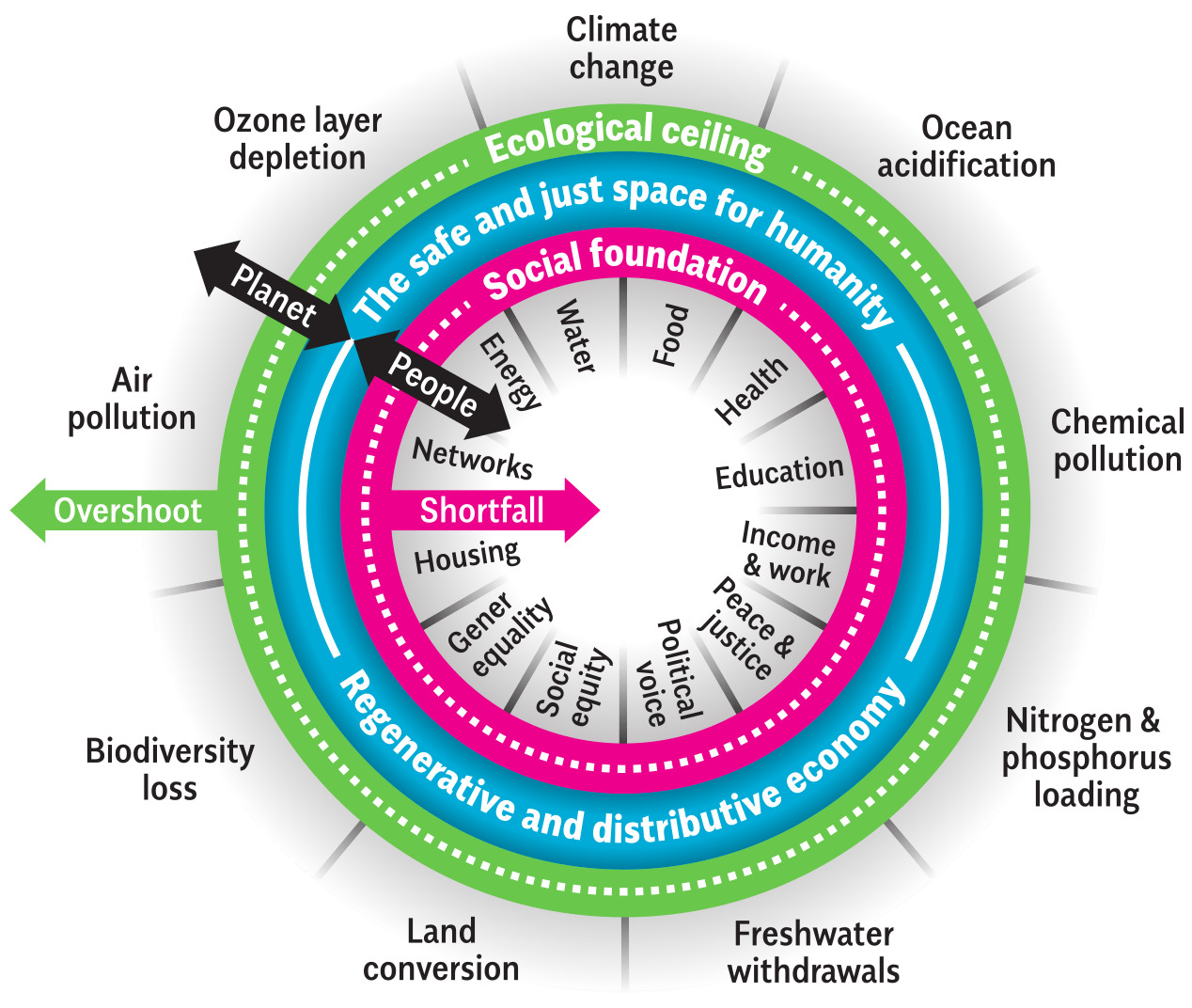

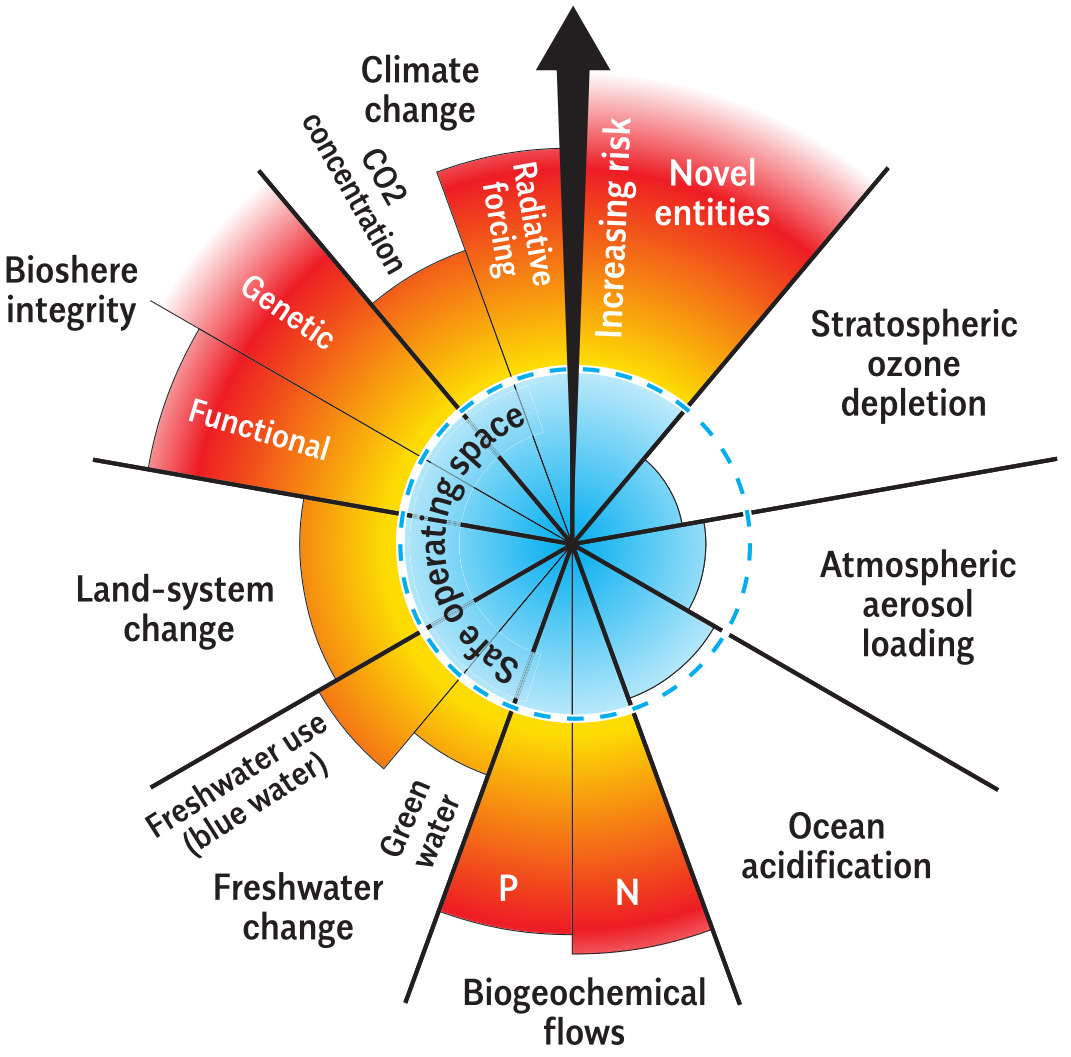

In a nutshell, Raworth’s doughnut economics is an attempt to identify "a safe and just space for humanity to thrive" — by drawing two concentric circles. It establishes minimum standards of living for humanity, the social foundation, and an ecological ceiling — the latter being the scientifically grounded limits to what the planet can take.

In between, on the dough of the doughnut, is that safe space.

The council has been moving towards this sort of understanding of our current predicament since at least Dave Cull’s time in the red robes.

By 2012, sustainability was a guiding principle across the DCC’s strategic framework.

"This is people and this is planet and that’s pretty much all you need to know," he says, summing up the twin rings of the doughnut, the inner social foundation and the outer ecological ceiling.

"These are all the things that people deserve to live a rich and full life and these are all the things that mean we might be able to do that for a little bit longer," he says by way of a little further elucidation.

"The systems are intrinsically linked that contribute towards social and environmental wellbeing, or not, as the case may be. So thinking of them constantly as being two sides of the same situation is really useful."

Councillor then and now Marie Laufiso sees it as a powerful communication tool, a way of explaining how we might all work in our various spheres for the benefit of all.

It’s a call to start thinking a little more holistically, she says.

"If our people are well they will treat the planet well, but if they are not being looked after themselves how can they focus on recycling or reducing, all that stuff?" she asks.

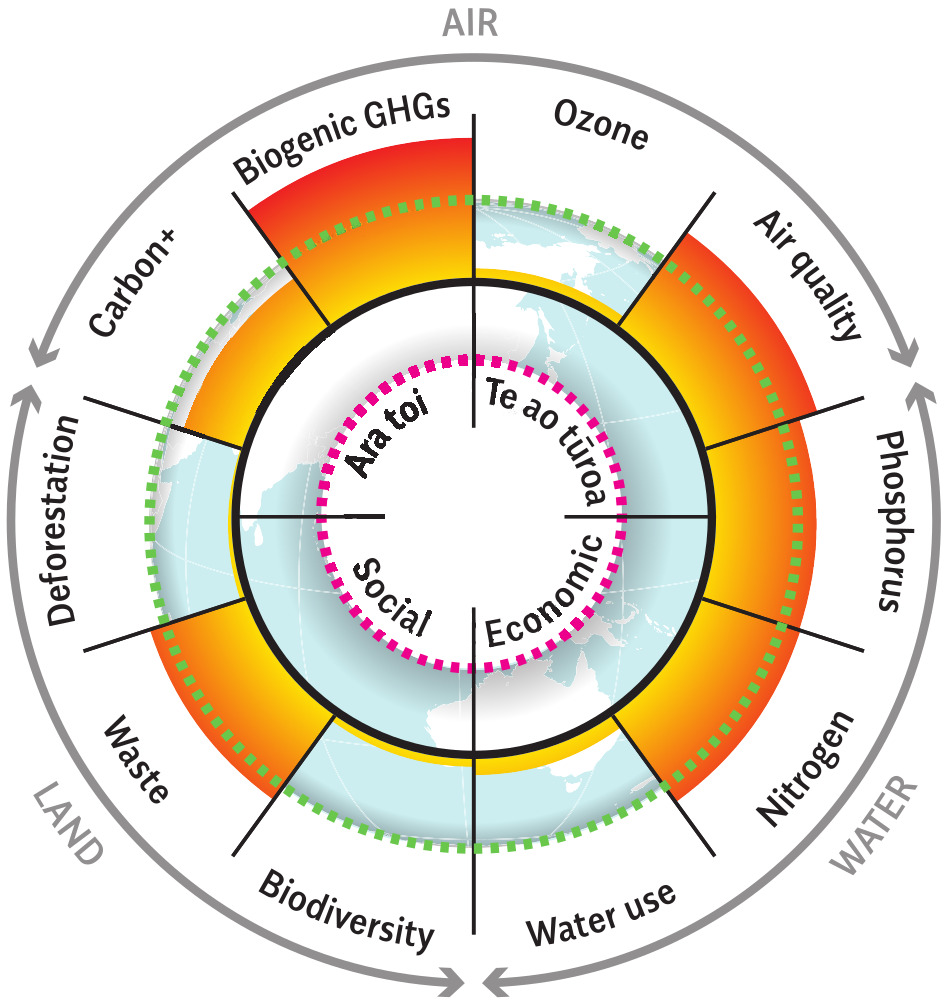

It’s big picture thinking, and at the same time the nitty gritty, which is pretty much the road doughnut economics has travelled to arrive here — from big existential planet-spanning science, to thinking about what a household in South D really needs from its council. At the big existential planet level, the starting point is the work by the Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC), which wrangled the science back in 2009 to determine precisely which of the planet’s ecological boundaries we’re trashing and by how much. They translated it all into a scary round graphic, great red flares of concern erupting out from the centre, crossing lines that should never be crossed.

They updated the graphic just this year, detailing nine mission-critical planetary boundaries that, if crossed, generate "large-scale abrupt or irreversible environmental changes". Climate change is one of the boundaries already crossed, as is biodiversity loss and phosphorus and nitrogen pollution. In fact, only three remain in the "safe operating space" and one of those, ocean acidification, is perilously close to the upper limit.

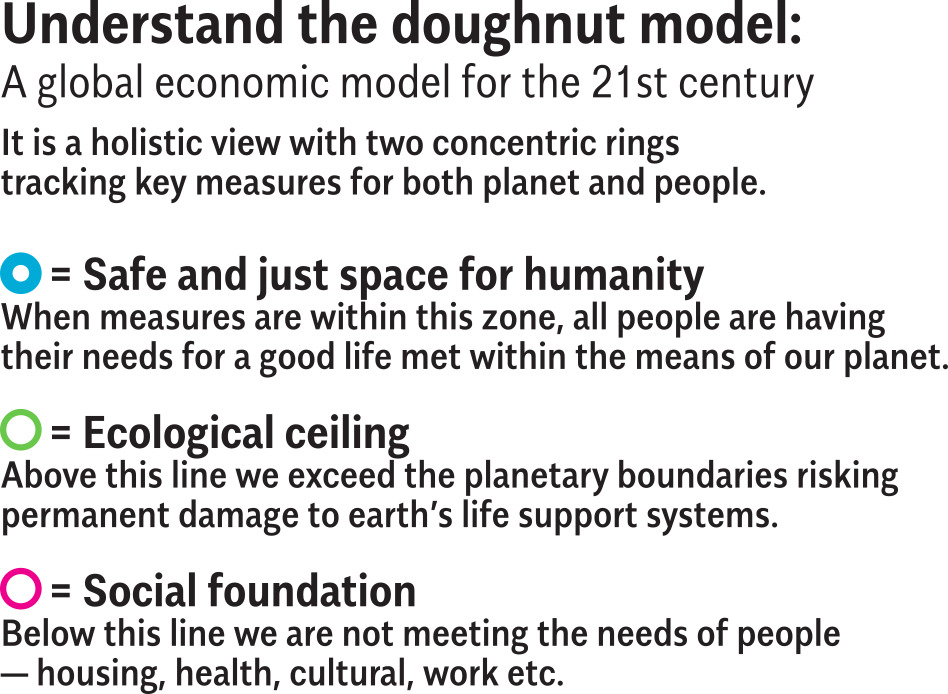

It’s outer ring, Dunedin’s ecological ceiling, was put together for the council by the Planetary Accounting Network (PAN), a Kiwi non-profit headed by Kate Meyer, which builds on Raworth’s research.

Raworth’s original work, a bit like the SRC’s, was big picture, but the British economist soon began looking at ways her doughnut model could be given practical purpose. Working with others, she developed the Thriving Cities initiative "to meet the goal of living well, within the means of the living planet", and from there the idea of City Portraits so towns and cities could start identifying where the pressure points were for them. Paris has been using the model to help it improve the water quality in the Seine ahead of the Olympics.

However, that work remained somewhat high-level, about visions and aspirations.

Dr Meyer has taken it and tweaked it further, converting those planetary boundaries to planetary quotas. Then, using those quotas, developing actionable portraits for towns and enterprises — each with "science-based, environmental budgets".

As an aside, Meyer is working on a format to include this sort of information — carbon content, waste profile, biodiversity impact — on the products we buy, like a nutrition panel but way easier to understand.

But back to the Dunedin City Portrait, the Dunedin doughnut.

"So, what we did with Dunedin was we went in and said, we can take that Thriving Cities framework and get all the good stuff out of that, there are some really neat tools in the Thriving Cities model, but what we can add to that is a really strong scientific basis for measuring impacts and setting targets, so that you have a really strong level of confidence that the targets you have set do actually mean you would be within those planetary boundaries," Meyer says.

For the draft Dunedin doughnut’s outer ring, PAN quantified 10 environmental footprints across wai (water), whenua (land), and hau (air), to establish preliminary science-based targets for each.

It might mean, for example, that if a paper were going to council with three options for a new road, one had a bike path with a line painted and one had a concrete barrier, you could assess the carbon and air quality and social health benefits of those options but then have the visual representation of the doughnut with green, orange and red indicators across the environmental and social parameters, Meyer explains.

"It makes it really easy for councillors to make what is quite a complex decision really quickly, because they can see, ‘OK, this has a lot of red in places that are really important to us and this one much more green or this one is orange but it meets that cost to benefit ratio that you are looking for. It gives them robust data that they can inform decisions on."

Handily for the development of the portrait, the council’s work towards a zero carbon by 2030 plan means they’re already flush with data points there. Among the areas where Meyer has recommended gathering extra data is for nitrogen. The council already has data for nitrogen levels in water, but quantities of nitrogen applied to land would complete the picture.

To take another example, the City Portrait identifies metrics to assess the council’s efforts to preserve biodiversity, but maybe doesn’t have the full picture yet.

The SRC’s science tells us we’ve crossed the line in terms of biodiversity loss, as measured by global extinction rates, but it makes no sense to talk about how many annual extinctions might be acceptable for Dunedin, Meyer says. However, we do need to know we’re doing our part.

So, for Dunedin, Meyer says we should collect better intel on land-use change, so we can use it to crunch the numbers according to the UN Environment Programme’s "potentially disappeared fraction of species" indicator.

We’d then really be in the game on that important ecological boundary.

It’s all pretty data dense, no doubt, but the PAN system’s heat maps translate everything into brightly coloured graphs in which the critical issues demand attention.

They might well grab attention beyond the city’s boundaries. Many councils are now into this sort of work, so Dunedin’s City Portrait has the potential to show a way forward.

Significantly, the Dunedin City Portrait is informed by Te Taki Haruru, the council’s recently finalised Māori Strategy Framework, an expression of the council’s commitment to the Treaty of Waitangi.

Te Taki Haruru too brings a holistic lens to the work of the council, while setting out how mana whenua and the council can lead together.

Its vision is "to see everyone in our city thrive and create a future we all want for the next generation, our mokopuna".

It sets out four wellbeing goals that will need to be met along the way — cultural, social, economic and environmental.

Ōtakou Rūnaka member Megan Pōtiki says the values underlying Te Taki Haruru, mana, hapu, mauri and whakapapa, inform the saying, "it takes a village".

"Which is kind of what Te Taki Haruru is about," she says.

"Those values are not for Māori, they are for everyone."

They can be applied broadly when we are thinking about the city’s waters, its roads, its infrastructure, its areas of need.

For example, mauri, which is life force, can be applied to the health of our water.

As the strategy says, mauri "makes us equal to our natural surroundings".

The strategy also talks of the concepts of tapu and noa, within the notion of "autaketake", "the holistic wellbeing of the individual and the collective".

In that context, tapu provides restrictions to keep people safe, Pōtiki says, it provides guidance

So, we can talk about waste water as tapu, she says, which helps us know what to do with it.

"It is actually a science, it is a Māori science of safety and we live by it."

The social foundation of Dunedin’s City Portrait, the inner ring of the doughnut, will be built on these foundations and earlier work by the council on its four social wellbeing strategies; Ara Toi: Ōtepoti Arts and Culture Strategy, Te Ao Tūroa: Dunedin’s Environment Strategy, the Social Wellbeing Strategy and the Economic Development Strategy.

The next piece of work for the council is to flesh out these wellbeing strategies to provide the sort of actionable metrics for the social foundation that PAN has already drafted for the outer ecological ring.

It has come up with draft "wellbeing concepts" for each of its strategies. So, for example, the social wellbeing concept is that "people are safe, healthy, connected and valued and can access resources and systems that support their sense of wellbeing". Below that are the wellbeing outcomes the council expects to see if its concepts are being achieved.

As far as social wellbeing goes, there are seven outcomes, including "people are connected", they have a "reasonable standard of living", and "live in affordable and healthy homes".

Council corporate policy manager Gina Huakau has been leading the work and says it will be up to the community to decide precisely what the targets should be. If homelessness were to be a measure of success, there would need to be a decision on whether to aim for zero homelessness, for example, or perhaps "functional zero", she says.

"That’s not council alone to decide that, that’s a city wide conversation."

Consultation is likely to run either as part of the 10-year plan process or in parallel. If finally adopted, the City Portrait will play a role in council longer-term strategising.

And yet, Hawkins says it represents an attempt to work across an even longer time scale than such local government planning documents.

"This is about taking a far longer view about what we want our society to look like and how we want it to function," he says.

Dr Meyer also sees it as very much part of a bigger picture.

"We have a few years left to decide the state of the planet for the next 10,000 years," she says.

It’s a big job for which we’ll need the right tools. Meyer believes the City Portrait is such a tool.

"It gives you that ability to make decisions about what is important to you, but informed by science and data."