The expansive, lush, green lawn edged by wooden buildings, shrubs and trees imbues the whole one acre, former school property, with a sense of sanctuary.

Double-hulled waka, half hidden by tarpaulin, speak to the community’s deep connection to this coastline and its active efforts to pass that on to the next generation.

The past is also present through a 4m-tall portrait of departed kaumātua Hoani Matiu, his thoughtful face painted large on what was once a school hall. The late authority on southern Māori traditions watches over those who are quietly busy in the native plant nursery and community vegetable garden propagating seedlings, harvesting vegetables for rūnaka seniors and weeding young trees awaiting transport to one or other of several planting projects stretching from the nearby Waikouaiti sandspit to farmland in the Maniototo hinterland.

A man stands on the doorstep of what, at a guess, was once the school library.

He is marine ecologist Prof Chris Hepburn, rūnaka manager Suzanne Ellison says.

There has been a long, collaborative association between the University of Otago’s Department of Marine Sciences and the hapū authority, Ellison says.

Today, Prof Hepburn is here with visiting seaweed farmers from Namibia, southwest Africa. For the rūnaka, it is part of ongoing planning for climate change adaptation.

"If there is going to be different sorts of farming going on in the marine environment, how do we feel about that?" Ellison says, explaining the potential-laden process rūnaka leaders are working through.

"Where do we want to be positioned in relation to that?"

Grimness might not fit here, but it seems an apt moniker for the world beyond.

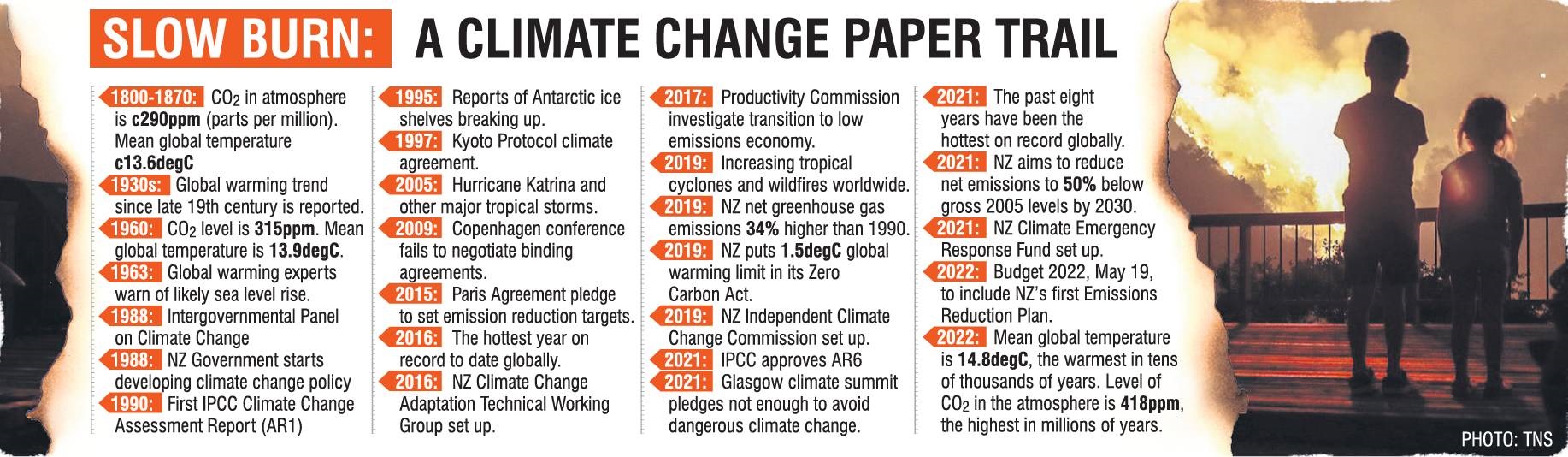

This week, temperatures in Pakistan and India have hovered close to a life-threatening 50degC, the highest on record for the sub-continent. It is the latest in almost a century of climate change observations that have included countless scientific papers, increasingly frequent and violent natural disasters and an unending cycle of global summits end-noted by ineffectual emission target pledges and ever-more dire warnings of climate catastrophe.

New Zealand, of course, has not been immune.

Winters are becoming warmer, glaciers are disappearing, ski seasons are getting shorter.

Rising sea temperatures have seen North Island kingfish chasing kahawai in the waters off Karitane and even in Otago Harbour.

Once-in-a-hundred-year floods and droughts now happen somewhere in this country most years. Within 20 years they will likely occur in Wellington every year, we were recently told.

Last week, a report said climate change combined with land subsidence means sea levels will likely rise twice as fast as previously predicted in some parts of New Zealand.

Three of the past five years have been among New Zealand’s hottest ever recorded.

Globally, the mean temperature is the warmest it has been in tens of thousands of years. The level of CO2 in the atmosphere the highest in millions of years.

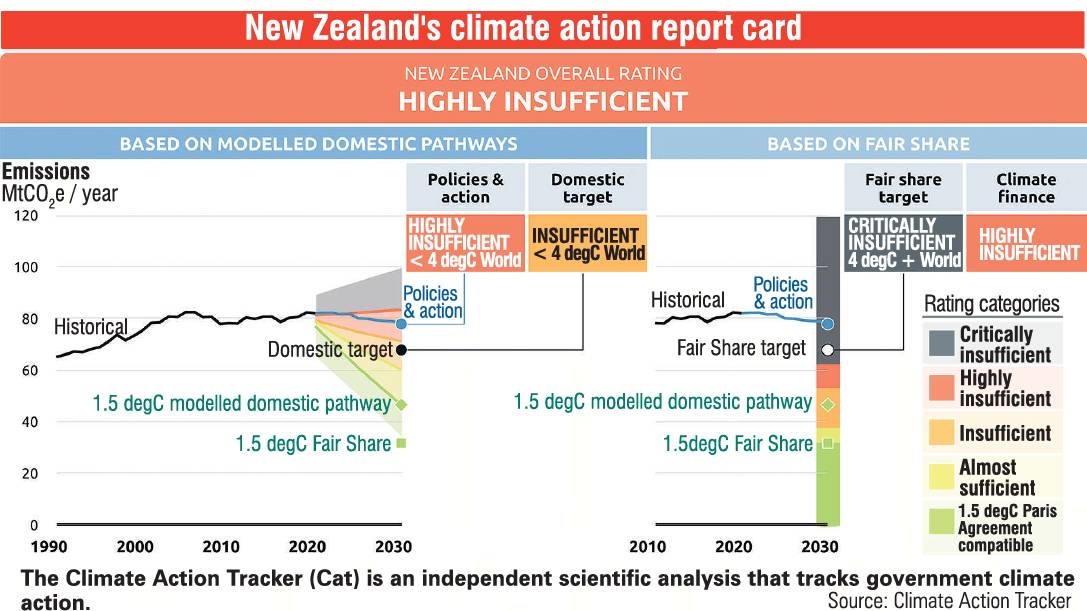

Right now, we are on a course to exceed 3degC of global warming - more than double the 1.5degC limit set in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns we only have until 2030 to halve greenhouse gas emissions if we want to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

On Monday, Shaw will give specific details about the Emissions Reduction Plan, New Zealand’s first serious attempt to help avert global climate catastrophe. The same day, Robertson will outline the first spending from the multi-billion-dollar Climate Emergency Response Fund.

That will be followed on Thursday by Budget 2022, which Robertson promises will go big on both health and climate action.

The Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) will be powered by emissions budgets governing the total amount of greenhouse gases New Zealand can put into the atmosphere during any five-year period. These budgets will progressively shrink, with an aim of reaching net zero carbon by 2050.

The ERP is the fount of a four-part funnel. Funding for the ERP will, in large part, come from the Climate Emergency Response Fund (Cerf), which in turn will be funded from the forecast earnings of the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). The ETS gets its revenue from New Zealand’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters, such as Fonterra, Z Energy, BP and Mobil — an anticipated $4.5 billion during its first four years.

Not yet included in the ETS, however, is the agricultural sector, which is responsible for 48% of New Zealand’s emissions.

Shaw promises Monday’s pronouncements, and Thursday’s follow-up, will give gritty detail on how exactly the ERP’s first three emissions budgets will cut carbon pollution from nearly everything we do — "from the way we grow our food, to how we generate energy to heat our homes, to the way we get around our towns and cities".

But those three budgets cover 13 years, to 2035.

According to the IPCC we only have until 2030 to halve our emissions.

For decades New Zealand, along with much of the rest of the world, has sat on its hands while climate disaster has rolled towards us.

Is the Government’s plan capable of getting the country, in just eight years, half way through a rapid transition to a radically different, equitable, climate resilient, low emissions future?

Will it be up to the job of economic and societal transformation?

Shaw and Robertson seem upbeat about its chances.

Shaw says emissions budgets "will ensure New Zealand is playing its part fully in the worldwide effort to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees".

“The Emissions Reduction Plan will be a blueprint for a more equitable, more prosperous, and more innovative future — and all within planetary limits."

Others have a much grimmer view.

"The ERP ... will be grossly inadequate," Dr Paul Winton says.

Dr Winton is a spokesman for All Aboard Aotearoa, a coalition of groups that have taken Auckland Transport and Auckland City to court. The coalition claims the city is acting unlawfully by adopting a 10-year Regional Land Transport Plan that will increase emissions by 6%, in breach of the Government Policy Statement on Land Transport which requires a rapid transition to a low carbon transport system.

The group of 300 lawyers has alleged in the High Court that the commission’s emissions budgets are inconsistent with limiting global warming to 1.5degC, that it has understated the country’s reduction targets under the Paris Agreement and that it is relying on other countries to reduce New Zealand’s emissions.

"It won’t even be close to what science and global equity demands of New Zealand," Dr Winton says.

He points to the Climate Action Tracker, an independent scientific analysis of governments’ climate actions measured against the Paris Agreement. The Tracker concludes New Zealand’s actions to date are "highly insufficient".

Dr Winton does not think the coming week’s announcements will change that.

"My expectations of the Budget are pretty low."

Dr Carter has retired from the University of Otago, where she researched indigenous Pacific responses to climate change.

The social anthropologist, who whakapapas to Kāti Huirapa ki Puketeraki, is still active in that field. She is the rūnaka’s representative on the Queenstown Lakes District Council climate reference group and on the Otago Regional Council strategy and planning committee.

Government inactivity, exacerbated by self-interest-driven reluctance on the part of citizens, is likely to mean it is "too little, too late", Dr Carter believes.

"We’ve got a lot of work to do. And I don’t see there’s a lot of willingness."

Dr Carter cites the absence of the agricultural sector — New Zealand’s biggest single emitter — from the ETS as a case in point.

"It’s all very well saying we’re going to do all these things ... but if they haven’t got contingency plans in place it’s not going to have much effect."

Some, however, rather than holding things back or holding their breaths, are just getting on with it.

Such as the Puketeraki rūnaka. It is several years along the road to climate change adaptation.

About six years ago, the overarching tribal organisation Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (Tront) began developing its climate action strategy, Dr Carter says.

Hui and workshops were held with each of the iwi’s 18 rūnaka to discuss climate change issues and clarify priorities.

Tront also commissioned reports by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (Niwa) examining how climate change was likely to impact the whole of the South Island and each rūnaka.

Kāti Huirapa also carried out an energy audit and a waste reduction pilot project.

The global Covid pandemic has interrupted plans, but they are now moving ahead again, Dr Carter says.

"We are one step ahead of many," she says.

"We know what is going to happen in our area ... so, we can plan and think about how we are going to cope with the changes that are coming."

The rūnaka has developed an expanding native plant nursery under the management of Angelina Young. The nursery has dozens of native species ranging from pīkao (golden sand sedge), harakeke (flax) and kāpuka (broadleaf) to tī kouka (cabbage tree), hakeke (tree daisies) and totara. The plants are going to climate mitigation and environment restoration projects in the local area and throughout the region.

Food security will be a significant issue, Dr Carter says.

In response, the rūnaka is expanding its community vegetable garden and planting an orchard on land near the marae.

"One of the key priorities is around he māra kai, our food resources, particularly our marine resources."

For example, southern rūnaka, through the tribal resource management consultancy arm Aukaha, are in early discussions with fish farm operators keen to talk about the possibility of more salmon farming off southern shores because waters further north are becoming too warm.

"We’re putting ourselves in a position where we can say, yes we’ve thought about this, and this is what’s going to happen, these are the bottom lines for us, this is what we’d like to see," Dr Carter says. Dr Carter suggests the Government, and the country as a whole, urgently adopts a different approach to the environment - an indigenous mindset - if we are to have any hope of adapting to a quickly changing climate.

"Being Kāti Huirapa, we experience the environment a bit differently," she says.

It is about kinship rather than domination.

"So, we learn from our environment as well as changing it.

"We learn by observing how it is changing, why it is changing and how we can adjust to those changes and live with it."

With that lens climate change can be viewed relationally.

Relationships need constant tweaking, Dr Carter says.

"There’s always something that comes up that impinges on the smoothness, the balance, of that relationship. How can we change the rules of engagement so we get back on an even keel?"

And as in any relationship, it does not work if one party believes they have the right to take, take, take.

"Nothing is ‘of right’. Understanding that is a big key.

"You have to think about future generations."

Recently, Dr Carter was reading the Government’s new climate adaptation plan.

It outlined the approach that will be taken for the next six years.

To her mind, it made grim reading.

"I thought, well, what happens after six years? Six years is nothing. We’re talking eight, nine, 10 generations out. What we do now is going to impact all those generations to come."