"Macrons," says Talia Ellison.

She’s been answering a question about the sorts of things people could do for Maori Language Week to extend their usage beyond "kia ora".

And rather than jump in and learn a whole raft of new words, Ellison suggests taking a step back to concentrate on pronunciation.

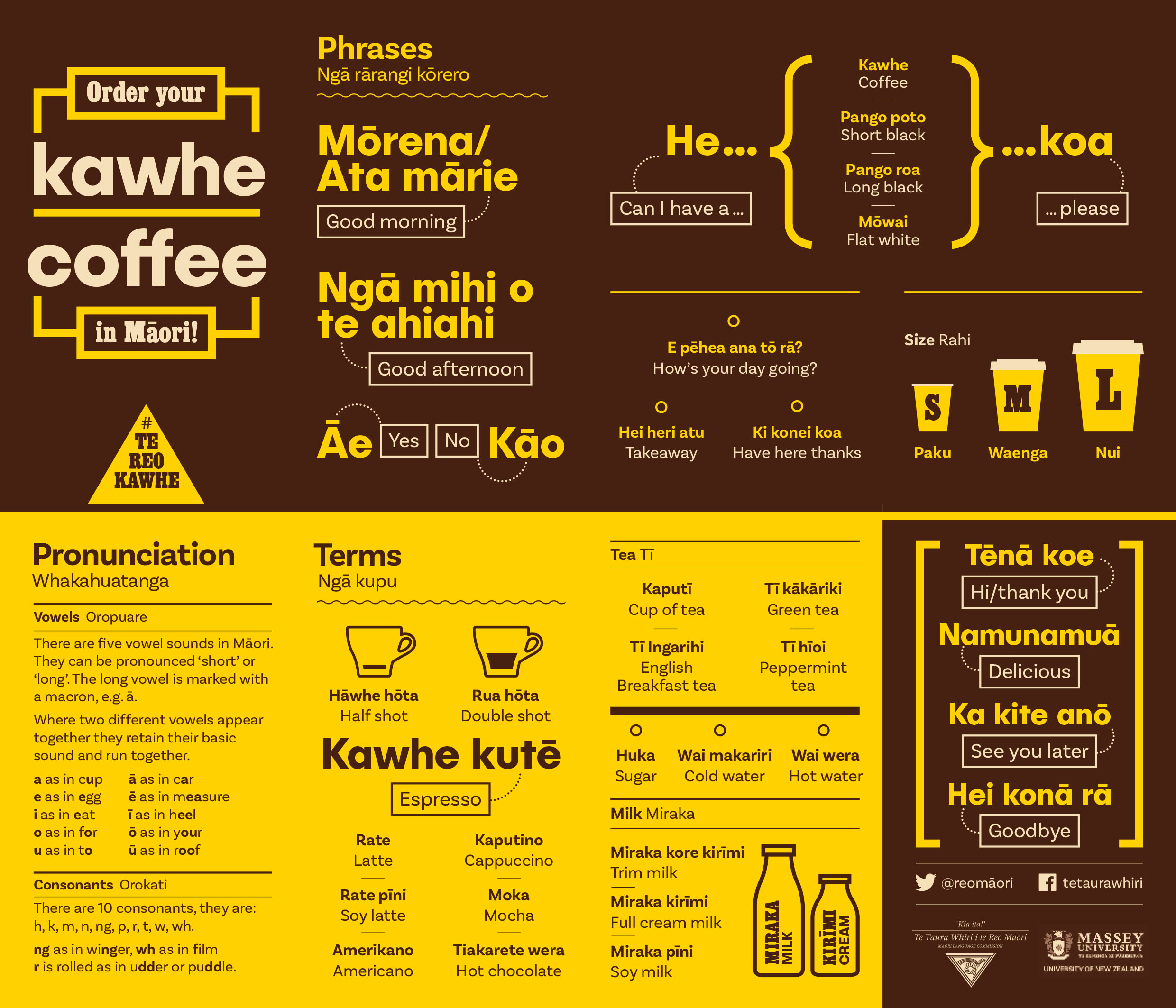

That’s where the macron comes in. Te reo Maori, an oral language, is rendered on the page using letters from English. But English doesn’t have letters to cover all the sounds and emphases, so written Maori employs the macron.

Unfortunately, the Otago Daily Times’ system doesn’t support macrons — the short line that sits above some vowels. There should be one over the "a" in Maori.

Those perennial solvers of problems large and small, the IT department, are working on it. But it is not proving simple.

So for the moment, The Weekend Mix is in a position to report Ellison’s advice but, unfortunately, cannot follow it.

Anyway, nail those vowels, says Ellison, who grew up speaking te reo Maori at Otakou Marae: a, e, i, o and u, and attend to whether they carry a macron or not (instructions above).

That done, it will be much easier to take the next steps, she says.

"Little things, like figuring out how to pronounce the place names that are in Maori in your area properly."

Maori Language Week runs from Monday to Sunday this coming week.

Maori Language Day is on Monday, September 14 and commemorates the presentation of the 1972 Maori language petition to Parliament. The theme this year is "Te Wa Tuku Reo Maori"(there should be a macron over the "a" of Wa), the Maori Language Moment. People are encouraged to do something at noon on Monday involving te reo Maori; say something, sing something, read something ...

That said, Ellison is a big advocate of normalising use of the language and has noticed her own proficiency fall away when she is not in situations where she can speak te reo Maori regularly.

Ellison, who studied te reo at the University of Otago and is completing a master’s degree through the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies looking at indigenous models of peace, says she was lucky to grow up well connected to her marae, Otakou (macrons over the first "o" and the "a"), so te reo was always normalised in her life.

She credits in particular her aunt Paulette Tamati-Elliffe, who is now Kotahi Mano Kaika (macron over the first "a" of Kaika) manager, leading Ngai Tahu’s strategy to reinvigorate the language under the kaupapa Kotahi Mano Kaika, Kotahi Mano Wawata (One thousand homes, One thousand aspirations).

After some time away from Dunedin and her marae, Ellison is now back in a situation where she can live the language a little more.

"I currently live with my sister and my nephew, who goes to kohanga. I pretty much speak exclusively in Maori to him, which is really good for me.

"I have this cool, wee Maori-speaking best friend."

She has noticed a change in the community around the use of te reo.

There is pushback, on the likes of talkback radio, if people appear to be deliberately mispronouncing words.

"There just seems to be some social changes happening where te reo Maori is starting to become normalised."

A trip to the supermarket has also gone from one where a Maori speaker might attract puzzled looks to one where the speaker might meet genuine interest and positive comment.

"Which can be a little bit frustrating when you just went to the supermarket to grab the cheese to finish dinner with — and this lady is having a full-on ‘wow, it’s so amazing you are speaking Maori’."

Not so good when the oven’s on at home.

It seems there is a new price to be paid for normalising te reo Maori in the community.