Forced migration is the new, hot topic in global foreign policy but it's of little relevance to ordinary Kiwis, right? Wrong, writes Bruce Munro.When Govinda Regmi and his family fled Bhutan for a refugee camp, he knew only one thing about the country he would wait 18 years to call his new home.

"In Bhutan, I didn't know where New Zealand was,'' Mr Regmi says.

"But in geography somewhere I had learned about the Canterbury Plains ... that it produces a lot of food crops. But I didn't know that it was in New Zealand.''

After fleeing to India in 1992, Mr Regmi and tens of thousands of fellow Bhutanese were herded into refugee camps on the Nepalese border. It was a period of chaos and heart-ache.

Life in the camps was harsh in those early days. Food and every other resource was scarce.

"One particular day, before the UN got involved, about 27 children died due to the cold and disease like fever and diarrhoea.

"During the whole day, we were on the river bank and people were carrying the bodies of babies and children past. That was a very, very negative day of my life.''

Today, seven years after arriving in New Zealand, and with a social work degree added to teaching qualifications gained in India, Mr Regmi is a cultural adviser and resettlement worker for the New Zealand Red Cross, in Dunedin.

Most people in his adopted homeland still know as little about Bhutan as he did about New Zealand, he says.

The average Kiwi, if they have heard anything about Bhutan, know of it as the country that measures its citizens' "Gross National Happiness''.

What most have no clue about, is the years of systematic discrimination, persecution and physical violence dispensed by the ruling northern Bhutanese on the ethnically and religiously distinct southern Bhutanese, precipitating the late-1980s crisis that turned 120,000 citizens into stateless refugees.

In a shrinking, globalised world, ignorance is no guarantee of separation. New Zealand is now home to a thousand of Bhutan's forced migrants.

And what has happened in that tiny country clinging to the slopes of the Himalayas, is being repeated in dozens of countries.

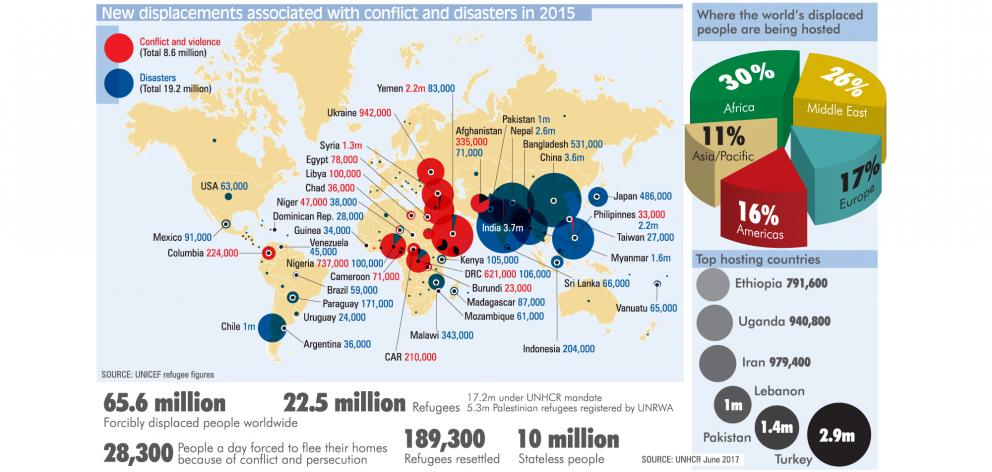

Internationally, we are experiencing the highest levels of displacement on record, says the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

An unprecedented 65.6 million people around the world have been forced from home. They include nearly 22.5 million refugees, most of whom are under the age of 18, and 10 million stateless people who have no automatic rights to education, healthcare, employment or freedom of movement.

Every minute today, nearly 20 people will be displaced due to conflict or persecution, the UNHCR says.

As a result, migration, which used to be a sleepy backwater of foreign policy, is now the hot, new topic, Associate Prof Jacqui Leckie says.

Prof Leckie is co-director of the 52nd Otago Foreign Policy School.

Each year the school, run by the University of Otago, attracts a top flight of international speakers as well as trainee diplomats, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade staff, academics and NGO representatives who gather to consider and discuss an aspect of foreign policy.

The school was held over the weekend. This year, the theme was "Open and Closed Borders: The Geopolitics of Migration''.

"You can't talk about Brexit and Trump without migration coming in to it,'' Prof Leckie says. "It is now at the centre of global political issues.''

That makes it a fascinating topic for school attendees. But it has about as much to do with most New Zealanders' daily lives as Bhutan's strict code of etiquette, the driglam namzha, right?

Wrong, say Prof Leckie and Prof Robert Patman.

Prof Patman, who is a University of Otago foreign policy researcher, says just because wars and other disasters are "over there'', we are not immune and nor should we be.

"We have to get out of this habit of thinking because something is geographically distant from New Zealand that it doesn't affect us,'' Prof Patman says.

Syria is an apt and tragic example, he says.

At the outbreak of the Syrian war, there was a tendency in New Zealand to think of it as "someone else's war''.

"But I think we are learning that in an interconnected world, if a problem like Syria is allowed to fester, and it has unfortunately, it affects many countries.''

Since the civil war began in 2011, about 400,000 Syrians have been killed, more than 6 million have been internally displaced and about 5 million have fled the country.

"We are affected by that process. We came under pressure from the international community to put our hand up and play our part. And we have.''

New Zealand is resettling about 1000 Syrian refugees, including about 200 in Dunedin.

We cannot have it both ways, Prof Patman says.

"One of the great blessings of globalisation for New Zealand is that we have been able to extend our activities and capabilities in the area of trade. But, as you get more involved in the international environment, it means you also accept the responsibilities that go with that.''

Forced migration is not just an "over there'' issue. It's impact is getting ever-closer, Prof Leckie says.

Asylum seekers from as far away as Afghanistan, Iraq and Iran have made up the bulk of the hundreds of "boat people'' trying to reach Australia during the past decade.

Australia's response has been tough. Those intercepted have been sent to a camp on Manus Island, in Papua New Guinea, or one on Nauru, in Micronesia, and told they will never be allowed to settle in Australia.

A Papua New Guinea court has ruled the Manus Island camp illegal, and Australia has agreed to close it.

As a result, some of the 800 men detained on Manus Island are petitioning to be taken to New Zealand, Prof Leckie says.

"How will New Zealand respond to this?'' she asks.

Prof Leckie knows what it feels like to be displaced. Co-directing the school could be the anthropologist's final act after having been made redundant by the university.

Prof Patman believes many New Zealanders are not impressed by Australia's approach to refugees and forced migrants.

"We are a very different country from Australia. The histories are different. The histories between the settlers and the indigenous people are different. I do think that affects our attitude.

"We are more relaxed about refugees than Australia. I think that reflects our different approach to race relations at home.''

Although Australia is probably our closest ally and friend, "there may come a point in the future when we feel we have to speak out'', he says.

Prof Leckie says New Zealanders need to realise forced migration is also originating in our own backyard.

Here, it is not so much because of armed conflict but rather climate change.

One of the speakers at this weekend's school was Ursula Rakova.

Ms Rakova, of Bougainville, has been involved in resettling people from the Carterets Islands, Papua New Guinea, where their homes and livelihoods are threatened by rising seas.

The UN's International Organisation on Migration estimates that by 2050 up to 200 million people worldwide could be forced by climate change to leave their homes.

"Climate change refugees is another new issue that will be more and more pressing for New Zealand,'' Prof Leckie says.

Given the country's "very special'' historical, cultural and economic links with the Pacific, we should be taking an active role in the region's migration issues, she says.

Pressure could come from an unexpected quarter, she adds.

Globalisation has triggered a reaction; a renewed sense of nationalism. Add economic uncertainty, and it is "very easy to see the answer in excluding certain groups of people''.

"There are global leaders like Theresa May and Donald Trump who are picking up on that very clearly.''

If Pacific people living in the United States are kicked out, that could have a flow-on effect for New Zealand.

"Are they going to return to the Islands, or are they going to be looking to come to places like New Zealand? If you are used to earning higher wages in California, you might not want to go back to Apia or Suva.''

At present, New Zealand's report card on its response to global and regional forced migration would be "doing OK, could do better'', the two professors say.

Most New Zealanders are "relatively tolerant'' of other cultures, Prof Leckie says.

"Sometimes, unfortunately, that tolerance just means ignoring things.

"I think we could do a lot better in relation to the Pacific. The Pacific has tended to be overlooked when it has come to migration, except when it's a problem. There's a tendency to see Pacific Islanders as a source of cheap labour. I think we do have a special obligation there.''

Prof Leckie believes the Government should consider raising the refugee quota above the 1000-person limit that comes into effect next year. Ensuring the country has the capacity to care for more refugees would be equally important.

Prof Patman says New Zealand has a lot to lose if it does not do more.

The country did well when it chaired the UN Security Council during 2015 and 2016, but needs to continue to push for reform of that organisation, he says.

"We have a big stake in trying to prevent situations like Syria being allowed to fester. The biggest problem is, while you have the permanent five group [on the UN Security Council], and while they have veto, it means they can play politics with situations like Syria.

"At the moment, some of the worst situations in the world cannot be resolved if one of the permanent five members of the Security Council objects.''

The country could also do more to respond to immediate, practical needs, he says.

"We have always seen ourselves as a good international citizen, someone that has no axe to grind internationally. So, it is a good example for us to set to be relatively generous.

"A lot of countries do ask why we are not doing more; countries that are much more pressed than us who are absorbing large numbers of refugees.''

Globally, less than 1% of the tens of millions of refugees get the opportunity to resettle in a new homeland, Mr Regmi says.

Finding his feet in New Zealand was not easy.

"It was very difficult, because it was so different,'' he says.

"New Zealanders need to understand how hard the refugee journey is. They do not leave by their own choice.''

But he was proactive, seeking work and building connections.

Although the first six months in New Zealand was a period of "suffering'', by the time a year had passed, Mr Regmi was feeling reasonably comfortable.

In 2015, this man from Bhutan, who had been forced from his home and ended up stateless for 18 years, became a citizen of a nation on the other side of the world. The seed of one disjointed fact planted in his mind on the slopes of the Himalayas had taken root and grown to provide shelter in the South Pacific.

"I felt so great when I got my New Zealand citizenship. I still feel a love about my country ... but I have no right to be there. Rather than Bhutan, I can now be proud of New Zealand.''