The second time their daughter tried to take her own life only served to show the desperate parents how little her disorder was understood.

At the end of a week in hospital care, the psychiatrist called a family meeting.

"His approach was, ‘you’re a badly behaved kid, buck up your ideas or you’re going to lose your family’," the father, Dan — not his real name — recalls, incredulous anger still in his voice these many months later.

"And his attitude to us as parents was, you’re just going to have to back off and let her go out into the big wide world and make some really bad decisions. He expected her to learn from it," Dan exclaims.

"I said to him, consequences don’t work for her. My wife challenged him too. She said, ‘chronologically our daughter is in her upper teens but functionally she is 12 years old or less’.

"We told the psychiatrist, ‘what sane parent would let their 12-year-old out on the street to run amok? That is what you are asking of us, and we simply cannot do that’."

It is a story with themes Assoc Prof Anita Gibbs has heard repeated many times in her years as a foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) researcher and advocate. The criminology and social work lecturer at the University of Otago, who began her working life as a probation officer, has spent a decade educating about the significant effects of alcohol on unborn children and dispelling ignorance about its profound, lifelong impact on people born with FASD.

"It is a brain-based disability that affects all parts of the body. It impacts them physically, mentally, emotionally, cognitively and spiritually," Prof Gibbs says.

"It is not a behavioural issue that can be cured with reasoning treatments."

This year, the Gama Foundation awarded Prof Gibbs a Critic and Conscience of Society award worth $50,000.

The award recognised her “extensive work” on FASD and her "depth of commitment to the critic and conscience role".

The acknowledgement is valuable and the money will help further her efforts, but there is still so far to go, Prof Gibbs says.

"Ignorance and disbelief is the problem — people not truly believing it exists as a disability.

"We’re trying to break through an attitude that says it is a deliberate, wilful choosing to behave poorly. Whereas, actually, it is a brain injury."

FASD can be thought of as something like preventable autism. But rather than a genetic origin, it is caused by the foetus suffering brain damage as a result of alcohol poisoning.

Alcohol passes straight across the placenta to the foetus. But whereas the mother’s body can get rid of the toxic chemicals, the developing baby cannot.

"With any amount of alcohol, the foetus is almost knocked out," Prof Gibbs says.

"It’s basically a poison, impacting the brain and the growth of the foetus."

It can affect all aspects of the person born with FASD. Common traits include impaired memory, impulsiveness, inattention, difficulty reasoning, trouble understanding cause and effect, difficulty reading social cues, mood fluctuations and anxiety. About 10% have distinctive facial features. A third have an intellectual disability, but 70% are within the normal range for IQ.

That something was amiss became apparent when she was still a toddler, and grew only more obvious with time.

"Emma is intelligent and articulate and highly sociable," Dan says.

"But she doesn’t understand the norms of social interaction and has no sense of stranger danger. Her thinking is disorganised and chaotic, she can’t sustain focus and effort."

Emma’s perception of the world is vastly different from most people’s.

"If she cannot clearly see an item is related to a person then she has no sense of ownership, no sense of ‘mine’ and ‘theirs’. If money isn’t in someone’s hand then it’s there for the taking."

Emma has had trouble maintaining friendships at school. At home, she has regularly taken money and food.

Between 3% and 5% of the population are thought to have FASD. That is between 146,580 and 244,300 people in New Zealand with some degree of this brain injury. It means 3000 New Zealand babies born with this disability each year.

But the numbers could be higher, Prof Gibbs says.

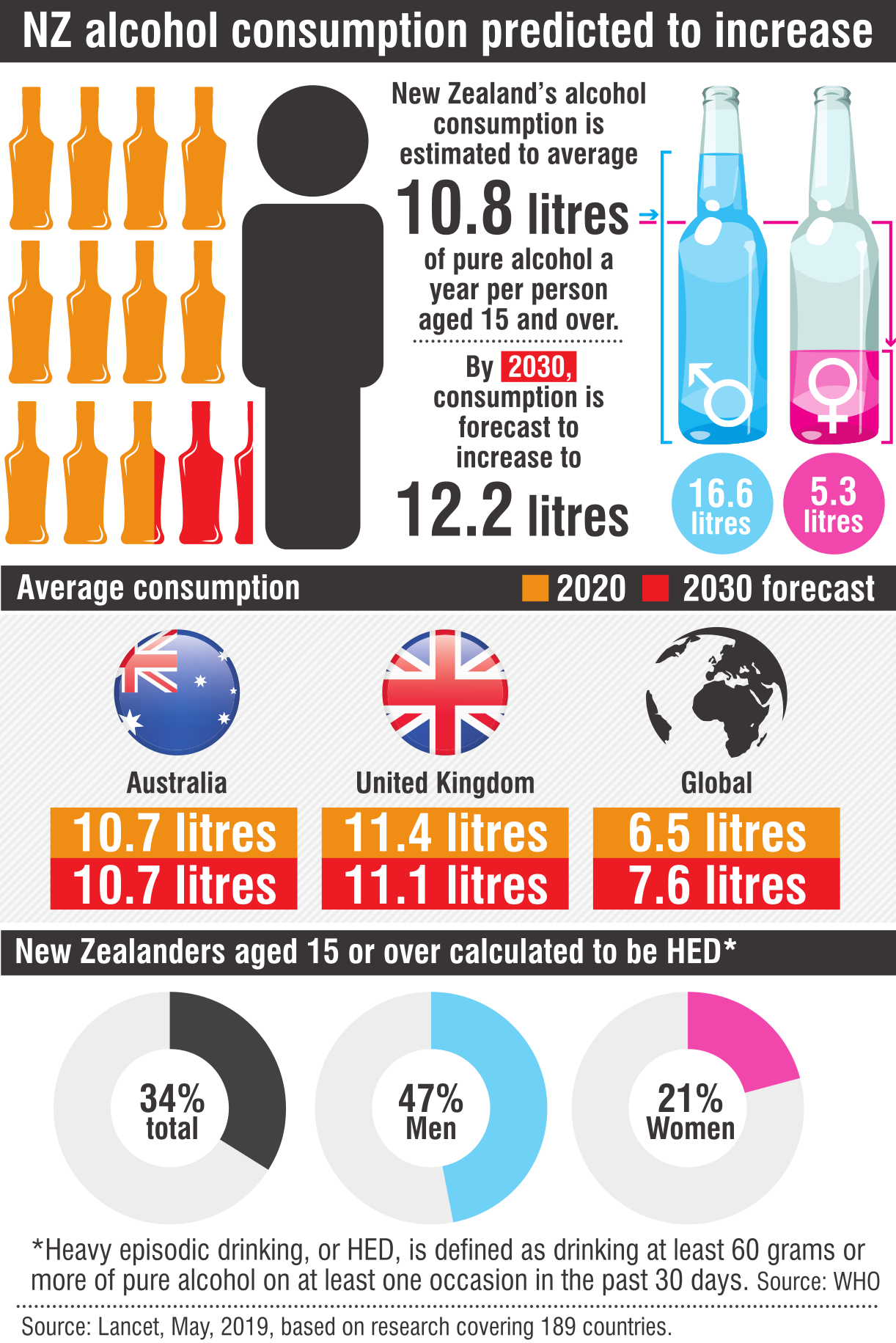

No studies of the prevalence of FASD have been done in this country, she says. And while it is known the global incidence is 3% to 5%, we also know the average alcohol consumption in New Zealand — about 10.8 litres of pure alcohol per person per year — is 66% higher than the global average of 6.5 litres.

Despite those numbers, ignorance is rife, she says.

"I’m trying to get people to shift from seeing them as naughty, wilful and wanting to cause harm, to most of the time ... suffering from memory loss and loss of reasoning capacity."

Dan and Sarah say Emma’s exploits, including more frequent running away, have brought them into contact with dozens of professionals. They have been consistently dismayed by the lack of awareness of FASD.

"Over the years, we have fought for help at every level," Sarah says.

They have battled counsellors treating Emma as though she was neuro-typical, had an occupational therapist who was helpful but ran out of ideas and a police psychologist who was learning about FASD by working with Emma.

Sarah has spent an "inordinate amount of time" contacting agencies and service providers to ask what programmes they have and what they can do to help.

"Everywhere we’ve gone, a number of them have said, we’re willing to help but we don’t know much about FASD."

In recent years the family have had a dozen police officers through their house.

"I’ve asked all of them what they know about FASD and all but one has said ‘What?’," Dan says.

One said he had heard of the term.

"Not one of them has had any training in FASD from a youth justice perspective. And none of them knew about the Teina Pora case. That was a landmark New Zealand case and they know nothing about it."

In 1994, Pora, then 18, was convicted of the rape and murder of Susan Burdett. He spent 21 years in prison before his convictions were quashed by the Privy Council. Crucial to his acquittal was the discovery that Pora had FASD. Pora had admitted to crimes he did not commit and his disability made him vulnerable to doing that.

A paper published last year in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry says awareness of risks posed to unborn children by alcohol dates back more than 2500 years. FASD symptoms were classified in the late 1960s and the first official public health warning was given by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 1977, the paper says.

Canada’s chief science officer says the alcohol industry has been aware of the risks for more than 20 years.

"It has taken so long because big business is concerned its alcohol-derived profit will be eroded by people choosing to drink less," Prof Sellman, who is director of the National Addiction Centre at the University of Otago’s Christchurch School of Medicine and Health Sciences, says.

"Thus, they have done everything they can do (with deep pockets and extensive networks) to thwart efforts to put health warnings on alcoholic beverage containers, against the advice of public health experts and advocates."

Prof Sellman believes alcohol should be regulated in the same way cannabis would be if legalised in the referendum being held as part of next week’s general election.

"The strong regulation proposed for cannabis would be great for alcohol."

The World Health Organisation says the best way to reduce alcohol-related harm is to dismantle alcohol marketing, increase price, raise the purchase age, limit accessibility and increase treatment options for heavy drinkers.

"FASD is part of this because FASD is an unnecessary major harm from alcohol, which would be reduced if these public health measures were enacted," Prof Sellman says.

Ignored and disbelieved, known but hidden. The concerning ways FASD is handled in New Zealand also include the fact it is recognised but not funded.

The Ministry of Health recognises FASD as a disability. There is even an FASD Action Plan. But FASD is not listed as a disability that qualifies for support services funding. Nor is it likely to any time soon.

In January, Prof Gibbs wrote to David Clark, then minister of health, again calling for comprehensive government support for children and young people with FASD. Six months later, on the day Dr Clark resigned as minister of health, she received a response. A week later, Prof Gibbs received a second identical letter from new Minister of Health Chris Hipkins.

The letter states "the Government and the Ministry recognise that more needs to be done to support individuals and families affected by FASD". It then outlines planned initiatives. However, the letter concludes, "with regard to eligibility for disability support services ... I am advised that the ministry does not currently have the funding to meet any increase in responsibilities".

Diagnosis involves a "barrage of neuro-psychological tests", has only recently become available in the South Island and costs up to $10,000.

"Which is utterly inaccessible for the average family," Dan says.

Sarah spent many hours researching their options and then many more trying to discover "which branch of which agency might have funding" they could apply for to get the screening done.

The FASD diagnosis confirmed for the couple that they were on the right track. Emma’s school was receptive. But the battle for help continued, even as Emma’s impact on the rest of the family, her risky behaviour, self-harm and run-ins with authorities escalated.

This week, in response to questions from The Weekend Mix, Hipkins said "screening, assessment and support of those with FASD is a priority for the Ministry of Health". People with FASD who also have another disability that qualifies for disability support services can get funded help, Hipkins said. But, he added, people with FASD who do not also have "an eligible disability" do not "currently fall within the Ministry’s funding responsibilities".

If the number of people in New Zealand with FASD is probably higher than the global average of up to five in every 100, then the number in state care and in prison is almost certainly off the scale.

Prof Gibbs estimates the proportion of those in care with FASD is one in two, 50%.

A 2018 study of young people in Australian detention centres reveals up to 90% have a severe brain impairment. Many of them will have FASD.

Recognising FASD as a disability but not properly funding it is just lip service, an angry Prof Gibbs says.

She wants to see proper funding, diagnostic services and interventions. Every child and young person going into state care needs to be screened, she says.

"We need system-wide change," Prof Gibbs says forcefully.

"What are they waiting for? When these children end up in the mental health and criminal justice systems we are talking about millions and millions of dollars a year. When perhaps if we intervened earlier ... But so often we are doing the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff."

Sarah is talking about Emma. Tears are streaming. Her voice is choking. The past two years have been horrible, she says.

"I went to a clinical psychologist crying and desperate. I went to my GP crying and desperate. I wrote a long email to the Commissioner for Children, crying and desperate, saying is there any help out there? And none of them had anything to offer."

So, with legal help, they insisted that Oranga Tamariki take back responsibility for Emma. That has been a rocky road, but in the long term it offers the best chance for their daughter, Dan says.

"When we took Emma on, we didn’t know the circumstances of her mother.

"Over time that came to light and we hoped we could make a real difference and break the cycle. We believed nurture would be stronger than nature.

"We look at where she is now ... and there’s a sense of failing her and putting her back into a situation that is far from ideal for her."

The hope now, Sarah says, is that Oranga Tamariki will find or establish tailored care for Emma and others with FASD.

"They are always going to need that external brain, that external structure and guidance to help make good and safe decisions. They need lifelong scaffolding provided by adults who understand them ... But unfortunately New Zealand doesn’t yet have that."

Comments

Around 2007, Invercargill ran an excellent "advert" on the radio warning of the dangers of Foetal Alcohol syndrome. It is another "tobacco" situation of big liquor business denying, eluding responsibility and persuading society to consume more. Liquor is everywhere in society now especially with supermarket and diary sales. All the harm of alcohol is society's cost.