Young people are angry. Faced with global inaction over increasingly dire climate change forecasts, frustrated and fearful youth worldwide have seized the activist mantle. Bruce Munro examines the insurgent youth-led climate action phenomenon.

Yesterday, as hundreds of school pupils throughout Dunedin left classrooms to vent their anger at the global climate catastrophe that scientists predict they will probably inherit, the four young organisers of the protest took some small comfort in what they had achieved.

For decades, a growing number of scientific voices have warned of a looming, human-origin, climate crisis. By the time the United Nation's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its most recent report, in October last year, 97% of the world's climate scientists were giving an unequivocal warning.

The world is on the brink of unleashing a cascade of unstoppable, climate-driven disasters that could irreparably disrupt or even end human life on Earth, they said. Only rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society can now prevent that scenario becoming a reality, they warn.

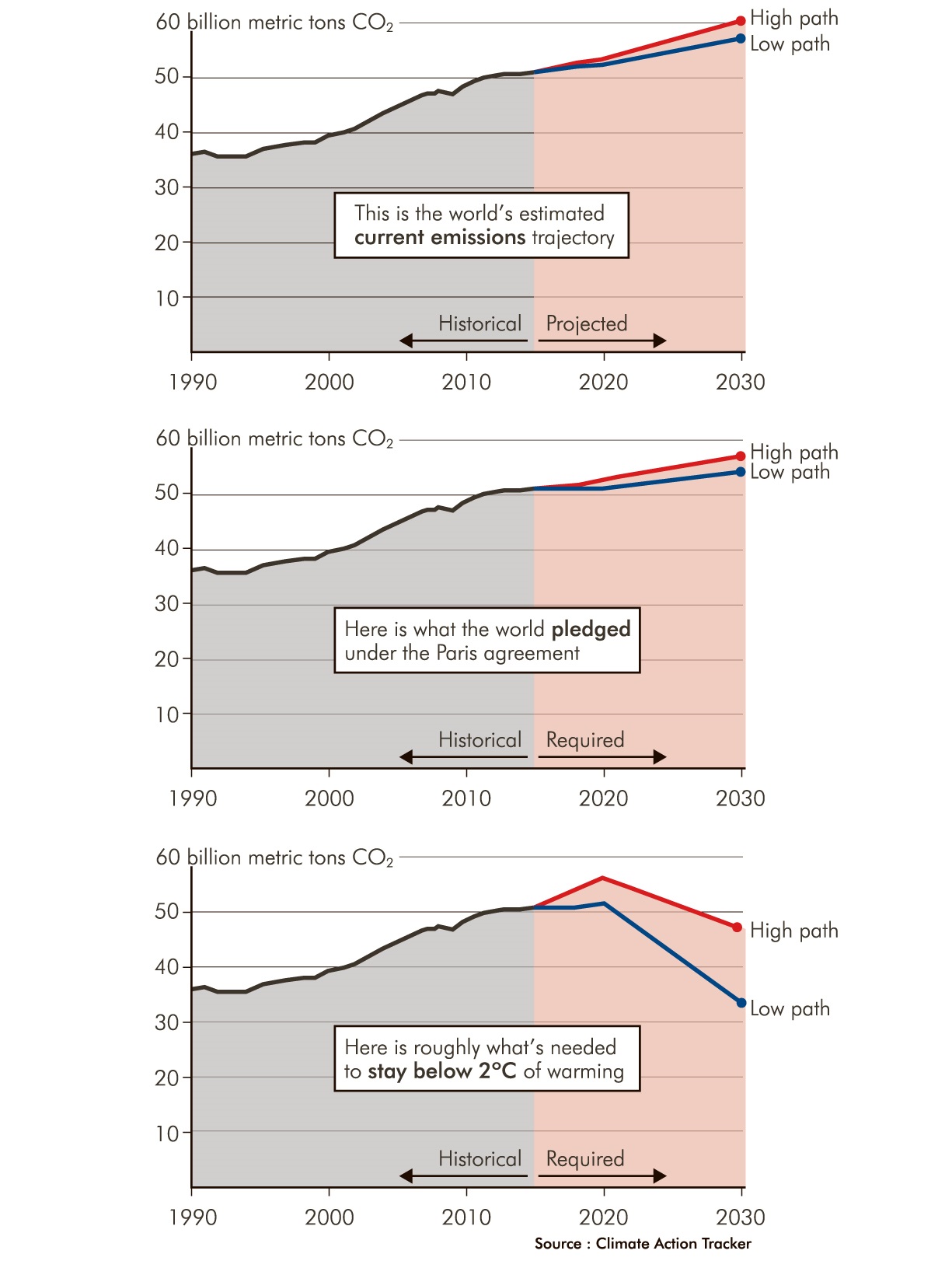

A dire warning. But not new. The call for action to avert climate change has been sounded for more than four decades. Evidence has amassed. Treaties and protocols have been signed. Targets have been set and ignored. Negative impacts have begun to be felt and seen. The chance to avert disaster is a narrow 12-year window. But still, worldwide greenhouse gas emissions grow.

In response, young people are taking matters into their own hands. In what has become a global movement, increasing numbers of people under the age of 25 are demanding urgent action. On the streets and in seats of power, political and economic, youth are making themselves felt and heard - "My future is under threat. This is your doing. Address it, now!''.

It is the ordinariness of the young people that is extraordinary. Perhaps not since the 1960s have so many young people been mobilised to protest. And their youthfulness is certainly beyond that of the counter-culture and anti-war activists of half a century ago.

The organisers of Dunedin's School Strike 4 Climate are four reserved, respectable teenagers not yet old enough to vote.

Finn McKinlay is the oldest. He is 17. Other members of the Dunedin Four are Abe Baillie, Linea Simons and Zak Rudin, all 16.

McKinlay takes science and music subjects at Logan Park High School. The jazz-dubstep band in which he plays trombone won the regional final of last year's Smokefree Rockquest. A few months later, he was selected for a national youth science leadership gathering that was held in Wellington, in December.

Baillie was drummer and a vocalist in the same band. His father is an ex-mountain guide-turned-quantum physicist. His mum is an author and editor of literary journal, Landfall. Baillie shares his parents' left-leaning political views. At school, where he takes mostly maths and science subjects, he is a music prefect.

Simons' mum is a nurse and her dad is studying for a PhD in peace and conflict studies. She is an able pupil across her wide-ranging subjects - painting, statistics, English, chemistry and biology. Beyond university, Simons hopes to work in environmental conservation.

Rudin comes from "a family of philosophers and academics''. His grandmother was involved in protests and demonstrations in the United States in the 1960s. Rudin got scholarship English while still in year 12. Next year, he hopes to study psychology and law at the University of Otago.

Young achievers. Not the stereotypical profile for frustrated, angry youth. But those are the emotions that keep emerging with their words - frustration, anger ... and a determination to bring about change.

"We see what is going on. And we see that nothing big enough is being done about it,'' Simons says.

"That's incredibly frustrating. Because you are going to leave us with this world that is so messed up.

"We can't vote, so we have to make our voice heard in other ways ... If we want something immediate to happen, we have to take action now.''

Off their own bats, they devised, planned, publicised and organised yesterday's Dunedin iteration of the global School Strike 4 Climate movement.

At their urging, hundreds of secondary, and even intermediate and primary, school pupils boycotted classes to make their call for climate action heard.

They marched with dozens of supporters from other environmental organisations and members of the public, gathering in the Octagon to add their voices to the global call for politicians, big business and adults generally to take climate change seriously before it is too late.

"For the past 12 months or so, we were becoming more and more aware of inaction on climate issues. It's been a build-up of internal dilemma,'' McKinlay says.

"It made sense to put all of that annoyance into making our voices heard and demanding action from those who are failing us.''

THEIRS is one expression of a global frustration that found a nexus, a face, a voice in August, last year, in Sweden, in the person of Greta Thunberg.

Then 15, Thunberg began skipping school to stage a silent, one-person, climate action protest outside Sweden's parliament. She said she was inspired by a march in support of gun control, in Florida, United States, organised by teenagers.

Thunberg gave out leaflets that read, "I am doing this because you adults are shitting on my future''.

She vowed to keep it up until the government took action on climate change.

The public began to take notice. International media began running stories on her.

Her action and tone resonated with young people worldwide. Within four months, more than 20,000 young people had taken part in climate action school strikes in a dozen countries.

In December, youth activists protested at the United Nations (UN) climate change conference, in Poland, and Thunberg spoke to the UN delegates.

On January 25, after a 32-hour train trip from Sweden to Switzerland, she addressed the world's political and business leaders, who had travelled by more than 1500 private jets to the World Economic Forum gathering to discuss man-made climate change.

"Adults keep saying, we owe it to the young people to give them hope,'' she told the audience.

"But I don't want your hope. I don't want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel everyday.

"And then I want you to act. I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if the house was on fire. Because it is.''

Globally, it is youngsters such as Thunberg who are getting cut-through, focusing attention on climate change imperatives.

In Canada, young lawyer Catherine Gauthier has sued her government on behalf of all youth for failing to tackle climate change.

Similar action is being taken in the US.

IN New Zealand, youth-led environmental group Generation Zero has championed the Zero Carbon Act. The Act would set greenhouse gas emission-reduction targets into law. It would also establish an independent Climate Change Commission charged with developing a framework to help the country meet those targets.

Climate Change Minister James Shaw has described the legislation as "directly the brainchild'' of Generation Zero.

It is hoped the Zero Carbon Act will be in law by the middle of the year.

Other environmental groups, especially those emphasising action over talk, are seeing their youth memberships grow.

Students for Environmental Action (Sea) Otago, based at the university, had 130 people sign up at the start of the academic year. That's about three times as many as last year, Sea co-president Katrina Thompson (21) says. The group's Facebook page has about 800 members.

"We want to activate students, helping people not just gain awareness but actually act to help,'' Thompson says.

"It is in people's face that ... we need to step up and actually do something, because it is our future,'' co-president Eilish Austin (22) says.

In 2016, Sea was instrumental in convincing the University of Otago to get rid of its investments in fossil fuels.

Extinction Rebellion (XR) has also deliberately chosen principles that foster action.

XR aims to use non-violent civil disobedience to force governments to treat climate change as a crisis.

Born late last year in the UK, XR came to prominence by mobilising thousands of protesters who blocked London bridges, bringing the central city to a standstill. In four months, it has spread to at least 13 countries.

While open to all ages, young people seem particularly drawn to XR's decentralised and action-focused ethos.

"We operate by consent, not consensus,'' XR Otepoti member Jamie Prout (25) says.

"That means sometimes some of our actions do not fully represent the group. But the sum of the actions would represent the group.''

XR members are "sufficiently concerned'' about the future of the planet to "do something a bit `out there' about it'', fellow member Danika Hotham (22) says.

"Everyone knows climate change is bad but they are just living their lives. We need to stop and see it is urgent and make a stand.''

Sea and XR members are effusive about the Dunedin Four and their school-aged counterparts who took part in School Strike 4 Climate.

"I'm really excited by their passion,'' XR Otepoti member Rachael Laurie (27) says.

"It's phenomenal. I'm really impressed. We need more young people like that,'' Sea treasurer Jonathon Visser (39) says.

For Baillie and his fellow protest organisers, it was simply a matter of doing what had to be done.

"This is a global crisis. This is the future of humanity,'' he says.

"The future of the world as we know it is at stake.''

"I feel angry,'' Rudin adds.

"We only have 12 years, at our current rate, until global warming ... becomes irreversible.''

Prof James Renwick says the Dunedin Four, Thunberg and all their young compatriots worldwide are justifiably fearful for their futures.

Prof Renwick is head of the School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences, at Victoria University. He is a member of the World Climate Research Programme's Joint Scientific Committee. On Tuesday evening, he was awarded the Prime Minister's Science Communication Award.

If no action is taken to curb greenhouse gases and global temperatures climb three or four degrees, hundreds of millions of people will be affected by impacts such as flooding, famine and warfare over resources.

"It is hard to overstate how bad the future could be if we do not take action on climate change,'' Prof Renwick says.

"All bets would be off.''

A sense of urgency is needed to avert a catastrophic future.

"What we do now, will determine what the future looks like.

"Sure all these scenarios are for the end of the century, but the action has to be immediately.''

The next 12 years are crucial, he says.

To stop global warming at 1.5degC, we have to halve global carbon emissions by 2030 and reduce them to zero by no later than 2050.

"It's a huge ask to turn the global economy on its head, virtually, in terms of energy production, at least. But that is the scale of the issue because we have left it and left it.

"If I was a school kid today, I'd be pretty upset.''

Upset, angry and not taking no for an answer.

![Associate Prof Karen Nairn: "We don't always know until we can look back [but] ... I do think...](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_portrait_medium_3_4/public/karen_nairn_hs_2_070319.jpg?itok=pKAB-bnM)

"We know the Government can act quickly, because they do, on certain things. We want them to realise this issue is important enough to put it at the forefront and do something. It's only the greatest crisis of our generation,'' Simons says.

Young people recognise the scale of change needed and are actively working towards it.

XR's goal is to mobilise 3.5% of the population in order overturn the present "toxic system''.

"It's about challenging the systems that are causing the big problems like climate change,'' Prout says.

"It's about social and system change that will then impact on the environment.''

No wonder the world's elite gathered at Davos were worried, sitting up and taking note.

Right now, this moment of youth-led climate action, will prove definitive, Associate Prof Karen Nairn predicts.

Prof Nairn, of the University of Otago's College of Education, is lead researcher in a multi-university study looking at what motivates young people who are engaged in social change.

The neo-liberal economic model has proved lacking. Populism is evidence of a global sense of crisis. Climate change is proving a powerful galvanising issue, Prof Nairn says.

"We don't always know until we can look back [but] ... I do think this is a unique moment in time,'' she says.

The capacity to envisage change and a different future, what she describes as hope, is critical to motivating the effort required to bring about that change.

"There are all kinds of emotions driving people to initiate or join groups to create change. Anger can generate a vision for how to do things differently.

"I do think hope is important. What we are interested in is ... what it means to talk about our hopes with other people and come up with a shared goal.''

"I want to live to an old age,'' Baillie says.

"I want there to be an environment for me to study and enjoy,'' Simons says.

"Not an environment that is so shattered there isn't much to study.''

"If you look at the massive ecosystem collapse that is already happening,'' says Rudin, "with insects that are crucial to the systems that we base our crops on - we are going to face profound problems if we don't do something now.''

This is only the beginning, McKinlay says.

"We've had some very positive responses and some negative responses,'' he says.

"It's highlighted for us that some people still think the issue is up for debate. So you can expect to see young people continuing to stand up to make their voices heard.

"Our futures are at stake.''