You will be surprised, maybe even scared, when you realise how much of your personal data is in other people's hands. Bruce Munro requested all the information held on him.

The biggest challenge, after the initial shock, is working out how to live well in this unprivate, digital age, he writes.

It arrived in four "dumps''.

One after another, in mid-afternoon, late in the week. Four packets of data, dropped into my email inbox. Each containing about 2GB of data, courtesy of Google.

I had made the application 48 hours previous.

It was a simple process. Click "download your data'', leave all 44 Google product selection options turned on and hit "create archive''. That was it.

Who knew you could politely ask the likes of Google, Facebook, credit ratings companies, Police, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service ... for all the information they held on you, and they would just hand it over? (Well, not the SIS, not for me at any rate, but we'll get to that.)

Who knew? Not me. Not until I read about a journalist in the United Kingdom doing something similar. And then, it seemed the obvious thing to try here in New Zealand.

There is disquiet in some quarters about our personal data being held by commercial and governmental organisations. There is unease over how much they know about us; troubling conjecture, fanned by some significant tidbits of evidence, about how that information is being used.

So, I went looking; hunting and gathering.

I searched online, filed applications, phoned organisations, requested information.

And then, waited.

Some took days to arrive. Some, weeks. Only one was rejected.

In the end, there was a weighty, digital stack of files.

But that, really, was just the beginning.

I began to take stock, flicking through many dozens of pages. Then, going back through again, more methodically, taking notes, building a dossier, on myself.

It was surprising, disconcerting, a little scary.

Here's a summary.

And, remember, what they know about me, they also know about you.

Google, through Gmail, has all my personal email correspondence. That's all the hundreds, probably thousands, of emails I have sent. Plus all the emails I have received, including all the spam emails I deleted without opening.

That was a moment of shock: realising Google has all the emails I have deleted. Not just the ones I couldn't be bothered with. It also has all the ones I didn't want to keep. Plus the ones I wanted to get rid of. Turns out that when they disappeared, it was because Google was swallowing them.

Google also regurgitated my entire browsing history.

It told me, for example, that at 3.13pm on July 20, this year, I Googled "15 great meals to make with canned tuna'', two minutes later I looked up a recipe for "Israeli cucumber noodle salad with tuna'', and by 3.18pm I'd moved on to "Avocado Tuna Salad''.

That is a level of knowledge of me that goes well beyond what even my wife and children possess.

It also spat back all the key search words, images, maps and You Tube searches I had ever made. Yes, Google has, in its hot little hands, a record of all your video searches. And it is going to keep them, forever.

I discovered it is also keeping a separate log of my phone use. Every time I watch the news online, use my banking app, play a game on my phone during work hours ... it is all logged.

Google knows the entire contents of my address book; names, addresses, phone numbers. It has all the photos and documents saved in my drive.

It knows that on April 17, this year, I spent $5.99 on my Visa card to rent The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert. I'm not sure I wanted anyone to know that, let alone a faceless, global, AI-driven machine with an eternal memory.

And that's just Google.

Opening the Facebook data dump, was another disconcerting trip down memory lane. All the Facebook posts I'd ever made, all the Messenger conversations, all the phone calls from my smartphone (including the telephone number, the name of who I called, the date and how long we spoke).

Remember all the people you sent friend requests to who did not accept? How about all the requests you received but deleted or ignored? No? Facebook does - including the names of anyone you've "unfriended''.

I was surprised to see Facebook has a separate file where it logs significant events and the messages relating to them. When I changed my phone number, got engaged, got married ... All my poignant life moments have been identified as such, grouped together, and a record kept of what sorts of social interactions they provoked.

It goes further. Facebook has used all that information - including a map of my movements around the country and the world - to build a personal profile. I am, according to Facebook, in the "established adult life'' category.

That is then broken down into 31 interest categories including photography, cruises, Kathmandu and John Lennon.

I paused to ask myself, is it Kathmandu, the outdoor equipment retailer or Kathmandu, the Nepalese capital, that I'm interested in? I'm not sure. But I'll bet Facebook is.

I didn't even realise I was a John Lennon fan. Clearly, Facebook knows me better than I know myself. Well, I thought, if I like Lennon I better start listening to some of his music.

Next, I opened my Police file.

The earliest entries were two convictions in 1986 for being a minor in a bar.

The file also had my home addresses during the past three decades and my phone numbers since 2006. There were entries for the two cameras and one hearing aid I'd lost. There were details about the night in 2015 that a lowered ute took off without stopping after crashing into my car, which was being driven by my second youngest son on the evening before his driving test.

Some interesting tidbits, but not too much there, especially compared with the social media giants.

The credit rating companies were a different story.

New Zealand has three such entities - Equifax, Centrix and Illion (formerly Dun & Bradsheet).

All three are keeping tabs on me.

Illion is following my progress across eight accounts, such as credit card and power providers. It knows that in August, last year, I got behind on an electricity bill and that in October last year and February this year I missed two credit card payments.

Centrix gives everyone a credit rating between zero and 1500. I was pleased to see mine was 1147, which was labelled "very good''. But was surprised to see I had that rating despite a black exclamation mark in an alarming yellow triangle next to a section of the file titled "Aggregated payment performance''. Apparently, during the past 24 months, across the eight accounts they were monitoring, I had had three overdue payments.

Centrix also keeps tabs on your court, company and insolvency records.

But its seven-year file was a mere child compared with Equifax' 23-year-long dossier on my financial affairs.

Equifax knows I've had 18 hire purchase accounts and how I've managed each of them. They have a month-by-month breakdown of my credit card, telephone, electricity and mortgage payments.

They know I've never missed a telco payment, but that my bank overdraft was over its limit 16 out of the 24 months to the middle of this year.

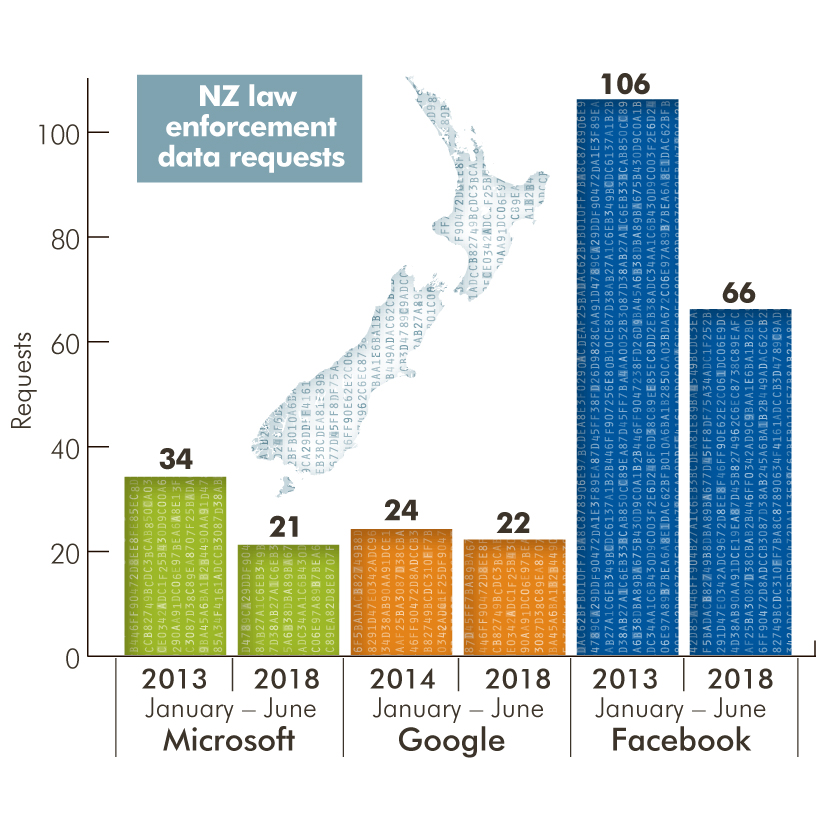

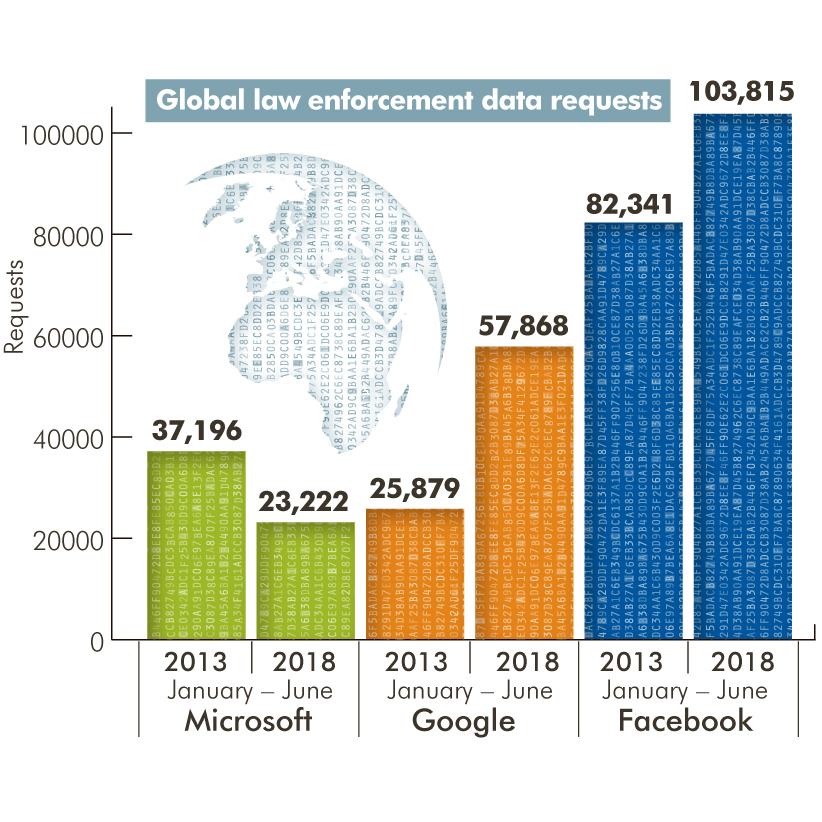

Worldwide, including New Zealand, law enforcement agencies are increasingly requesting social media platforms share data on individuals they are investigating.

I looked over all the notes I had made. It amounted to a lot of extremely detailed information. Assembled, it creates a comprehensive picture of what I think, say and do. Examined, it would be a highly accurate predictor of my aspirations and behaviours. Turned on me, it would be the blueprint for maligning, manipulating and milking me. Or you.

Of course, maybe they don't have that much information on you. They might have more.

With a bit of effort, it is easy enough to find out.

Confronted by the detail and scale of my personal data held by others, the pressing question was, what are they doing with it?

I sniffed around a bit, made a couple of phone calls, read online, read between the lines.

The bottom line - they sell it to people who want to sell things to you.

Not the Police. We'll talk about them shortly. But, the others, that's what they exist for, primarily.

The credit ratings companies make money by collecting financial information on lots of people and then charging businesses to peek under the covers and see whether current (and potential) customers are a good or bad credit risk.

They are also, increasingly, selling data to marketers and retailers.

Illion, for example, based in Melbourne, boasts on its website that it has almost 1000 staff gathering and providing data on more than 20 million individuals.

What it offers "spans the full customer life cycle, from lead generation and sales prospecting, to credit risk assessment and decisioning ... and, ultimately, receivables management''.

It says its databases and services can help businesses "build customised lists of targeted prospects ... profile best customers ... and make smarter marketing decisions''.

In this, credit ratings companies are following the lead of the likes of Google and Facebook, turning information about you into a sellable commodity.

An explanation of how those online giants do that arrived in an email from my features department editor Tom McKinlay.

We had been talking about data privacy and data commodification - no, it's true, we had - and he emailed me the link to an article by United States-based technology consultant Shelly Palmer.

In mid-September, Palmer had written a blog in response to US president Donald Trump's angry tweet about the lack of positive search results when he Googled "Trump News''.

"Google is not a search engine,'' Palmer wrote.

"It is a highly specialized direct response advertising engine purpose-built to translate the value of 'intention' into wealth for Google (Alphabet) shareholders.

"It is optimized to put the right ad in front of the right person at the right time. In other words, it is 'rigged' to optimize revenue - all other considerations are secondary.''

In the article, Palmer outlined the different sorts of knowledge the behemoths of cyberspace harvest to sell.

Facebook knows what you pay attention to, he says.

"Your Facebook profile makes your attention actionable.''

Amazon knows what you consume and are thinking of consuming.

Netflix knows your passions.

"Netflix knows more about the kind of entertainment that ignites your passions than you do. It continually acts on that data.''

Google knows your intentions.

"Your Google profile indicates, with a very high degree of accuracy, what you are likely to do in the near-term future. This is some of the clearest, most actionable data in the world.''

It reminded me of statements in a Royal Society research article published in August.

Professors Patrick Wolfe and Sofia Olhede, both of London, wrote that large volumes of data are being collected from people who are sharing information about themselves "without a clear understanding of the risks and opportunities involved''.

The professors warned that "the availability of large and detailed personally identifiable information ... [means] much more can be inferred from them than seems to be available at first glance''.

They also cautioned against throwing the data baby out with the bathwater. Using syllable-heavy jargon, they said, in essence, that lots of information on lots of people could be helpful.

A couple of phone calls and a few conversations later, I had reorganised the personal data collectors, and the way the information is used, under three headings - the good, the bad and the questionable.

Detailed data about a lot of individuals can improve people's health, fight corruption and help tackle social problems. Some government departments in New Zealand do this. These include an agreement between the ministries of Social Development, Health, Education, Justice and the Police to share information in order to identify and protect vulnerable children and promote the wellbeing of them and their families.

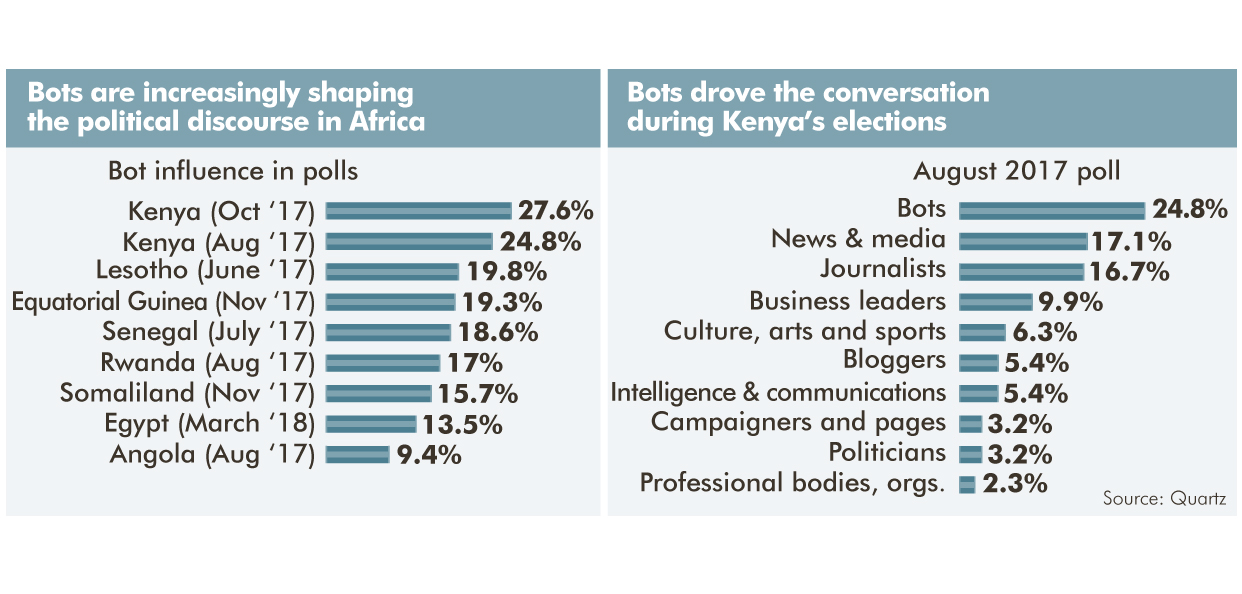

Combining the psychological profiling potential of globally harvested personal data with the AI technology of trigger word-laden chat bots, shadowy, maleficent figures (widely thought to be of mainly Russian origin) are believed to have manipulated the surprising election of Trump in the United States and the crisis-provoking Brexit vote in the United Kingdom. Reports of similar attempts have come from countries as diverse as Egypt, Brazil, Kenya and Germany.

Also likely on Santa's lump of coal list are those behind the Chinese government's attempt to introduce a nightmare version of Facebook. Like a real life episode of Dark Mirror, China is introducing a mandatory social credit ranking scheme for its 1.37 billion people. Due to be fully operational by 2020, it will monitor behaviour and give everyone a credit ranking, with consequences. Drive badly, smoke where you shouldn't, buy too many video games, post fake news online ... and you get a thumbs down, a low rating. Those with low ratings will find their travel, accommodation, education and job opportunities are reduced. Conversely, thumbs up behaviour will be rewarded with power bill discounts, lower bank interest rates and, apparently, more matches on dating websites.

Under the "Questionable'' heading is Police crime prevention and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service.

Police worldwide, including ours, are trying to harness the power of data technologies to predict, and therefore prevent, crime. At the heart of this revolution, is cutting-edge information technology that monitors social media and combines it with police files, personal information from government departments and client data requested from businesses. Police use this potent mix in two ways: to investigate crimes that have been committed and to identify potential problems and deal with them, not after, but before crimes are committed.

The concern about this is that democracy relies on people being willing to rock the boat, but surveillance suffocates that instinct and changes people's behaviour.

Labelling the NZSIS use of personal data questionable is simply because I do not know.

My Official Information Act request to the SIS for my file received a cryptic response. Yes, they did have information on me and copies of articles I'd written. But, no, they could "neither confirm nor deny the existence or non-existence of any information''. Signed, yours sincerely, Rebecca Kitteridge, Director-General of Security.

I appealed to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner. One of their investigators gave me a call, ostensibly, I believe, to ascertain whether I was paranoid. That was the motivation for quite a number of SIS file requests, I was told.

A month later, a letter from the investigator arrived. We can't tell you why, but we agree with the SIS decision, it said.

I'm as dangerous as a rubber knife. The most likely reason my file remains sealed is that one or more articles I've authored, which the SIS has taken a shine to, if that information was made public, could alert someone to the fact that the security agency has them in their sights.

But I don't know for certain. So, questions remain. Which, undoubtedly, is exactly how the SIS likes it.

The vast amount of my personal information out there, sloshing about, is disconcerting. And I am just one of about 4 billion internet users worldwide whose data is constantly being yielded and harvested. Were any steps being taken to address that, I wondered.

Some, it seems.

In May, the Europeans enacted the General Data Protection Regulation. A key aim of the GDPR is to give people greater control over their personal data. This week, the Australian Commerce watchdog has recommended people be able to have their data deleted and be able to opt out of having their information collected at all.

In New Zealand, a Privacy Bill is making its way through Parliament. A spokesman for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner says that although the Bill will introduce mandatory date breach reporting and increased fines, it does not go far enough.

"We believe the Bill does not do enough to account for advances in technology, introduce meaningful consequences for non-compliance and align with international best practice,'' the spokesman says.

We are still largely on our own, I conclude. Stripped naked, often with our naive consent, by the world's all-knowing data harvesters who then turn around and try to sell us underwear.

How do you live in such a world? What are the options?

They seem to range from pulling the plug or playing the ostrich to raging against the machine or gaming the system.

But, I think, there must be another way; a way to be in the world, but not of it.

Here's my three suggestions to myself for dancing with this digital age. You're welcome to any or all of them.

1. Stay thoughtfully engaged. There is plenty about digital technology and what it offers that is interesting, entertaining, informative, time-saving, even life-saving. We need people willing to give their data to create comprehensive pictures on which sound public policy can be built. Just, don't be naive or gullible. Be ever vigilant; aware that people are using the online world to try to distort your perspective and manipulate you for their benefit, not yours.

2. Be honest. There are powerful and legitimate uses of data in the hunt for, and prosecution of, people who have done wrong to others. There is no need to get caught up in that if you keep your nose clean.

3. Be brave. Increasingly, we need thinking, reasoned, informed voices online. We also need people to take principled stands in the real world. These actions will be recorded for posterity in the digital world. And yes, there is no guarantee those in control of the future will look kindly on those principled actions and voices of today. But brave people might prevent that world becoming a reality.

A bit grim?

There's always YouTube and Netflix.

Data Detective: How to get your personal information

GOOGLE

Go online to https://takeout.google.com/settings/takeout

FACEBOOK

Go to the top right of your Facebook page and click the small down-facing arrow.

Click 'Settings'.

Click 'Your Facebook Information'.

Go to `Download Your Information' and click 'View'.

Add or remove categories and select other options.

Click 'Create File' to confirm the download request.

CREDIT RATING COMPANIES

You can ask for your data from the three credit rating companies that operate in New Zealand; Equifax, Centrix and Illion.

You will find links to the application process for each company by going online to the government website www.govt.nz/browse/consumer-rights-and-complaints/debt-and-credit-record...

Comments

very good you woke up and smelled the roses.

The idea of surveillance pleases fatalists: those who believe citizens are powerless in an Authoritarian State. It is, of course, rubbish, as long as Cheryl Gwyn is our spy 'watchdog'. Recent events show that private organizations are the most problematic.