The Tax Working Group has released an interim report on overhauling New Zealand’s tax system, but failed to recommend a land value tax. Here’s why it’s a missed opportunity to make most of us better off, writes Bruce Munro.

It is sadistic that, on the way to passing Go and collecting $200, you have to run the gauntlet of Oxford St, Park Lane and their similarly overpriced siblings. It is Russian roulette, with most barrels loaded with crippling rent.

Unless, of course, you are the owner of these swanky green and navy properties and have built houses on them, or better still, hotels. Then you are as gleeful as a black widow spider sensing prey caught in her web.

That is how Hannah Allan is feeling - like the roulette player, or the moth, not the spider.

In this game of Monopoly, played at the Otago Daily Times offices late on a weekday afternoon, it has not been Allan's fortune to end up with any of the high value properties.

She has canary yellow Piccadilly and friends, as well as mid-priced Marlborough, Vine and Bow Sts. Oh, yes, and humble Whitechapel and Old Kent Rds, plus pocket money-earner Water Works.

Across the table sits her opponent, Mr Monopoly, who owns everything going on the high-value quarter of the board from Regent St to Mayfair, including the Electric Company and Liverpool Station. Mr Monopoly also owns the other three railroads.

At this stage of the game, Allan is extremely unlikely to win. She has about a quarter of the cash of her opponent and once again is poised to round the final bend. At the far end of the straight lies Go, but between her and the much-needed $200 are properties with houses that, if she lands on one, will cost her between $1100 for staying on Regent St and $1400 for a night's kip on Mayfair.

It bears some striking similarities to her life.

Allan (21) grew up in Queenstown, a burgeoning town with all the necessary amenities, surrounded by stunning natural beauty and plenty of enticing outdoor leisure options.

It was special. It was also simply "home'' - the place she lived with her parents and three older siblings, where she went to school, made friends ... lived life. As did four generations of her family before her.

In 2015, Allan shifted to Dunedin to train as a nurse. She graduated at the end of last year and now works at Dunedin Hospital.

She does not foresee a return to Queenstown. Not because she does not want to. But, because she cannot afford to buy a house in her home town.

HOUSING affordability has been declining throughout New Zealand for the past decade.

In July, the median national house price was $550,000. In Auckland it was $835,000. In Queenstown-Lakes it was just over $1 million.

Getting out of the rent trap and on to the property ladder is getting increasingly difficult. In Queenstown-Lakes it is nigh on impossible unless you already own property.

A sizeable portion of those who do own property in the district are wealthy absentee owners. It puts a vice-like squeeze on the market.

Those with capital get more. Those without, bleed. The inequality gap widens.

It is much the same as the world famous board game this young New Zealand nurse is playing. It looks bleak.

Then, suddenly, the rules change.

Allan still has to pay if she lands on someone else's property. But now, she pays the basic rent on the unimproved land into a Public Treasury and pays the remaining rent to the property owner.

As the Public Treasury grows, the money is used to buy back utilities and railway stations, making them free.

All other taxes, except for the unimproved land rent -in effect, a land value tax - are done away with.

As the public coffers continue to be topped up by the players' land value taxes, the money paid to players passing Go also increases.

Quite a different game begins to unfold.

WHO doesn't like a good old fashioned Tax Working Group?

Every decade or so, whichever government is in power sets up a Tax Working Group (TWG) to examine and potentially overhaul New Zealand's tax system. The Labour coalition's TWG, under the chairmanship of Sir Michael Cullen, last week released some interim recommendations.

For most people, talking about tax is a sure-fire cure for insomnia; something best left to pointy heads and bean counters. But tax lies at the heart of deciding what sort of country we want to live in.

Who is taxed, what is not taxed and how much is taxed is a direct extension of a nation's values and world view.

If tax is primarily to finance government, how big or small a role should government play in our lives? Should taxation be used to stop too much wealth accumulating in too few hands? Are taxes the best way to pay for the negative impacts of our consumption? Or, are taxes themselves doing harm, dampening incentives to work, invest and spend?

Taxes come in all shapes and sizes, but can be herded into two large camps, either direct or indirect taxation. Direct taxes include income tax, corporate tax, New Zealand's ACC levy and capital gains tax. Indirect include goods and services taxes (GST), fuel and alcohol taxes.

The TWG's interim report supports the introduction of a capital gains tax, finds a case for environmental taxes and an excise on sugar.

One tax that did not make the cut despite having wide "expert'' support, not to mention a surprising history, is a land value tax (LVT).

An LVT is a tax on the unimproved value of land, that is, the land itself and not anything built on it.

The idea is an old one, but it was given the biggest nudge by 19th century American journalist, Henry George.

Puzzling over the poverty he observed in booming 1860s New York, George realised much of the wealth of the city was ending up in the pockets of landowners, who did nothing to develop the city but were taking most of its riches through rents.

In 1890s America, his book on the subject, Progress and Poverty, was only out-sold by the Bible. George called for a land tax to be the single tax that replaced all other taxes. His cry was picked up by no less than one of the greatest writers of all time, Leo Tolstoy, who championed it in his last novel, Resurrection.

It also inspired the creator of Monopoly.

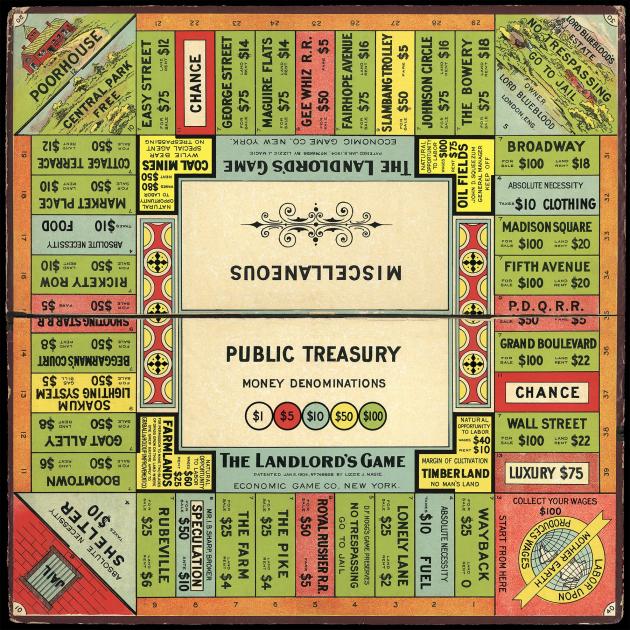

Most people do not know that the original version of the globally recognisable board game had two sets of rules. Nor, that it was devised to illustrate the evils of unfettered property markets and the benefits of a land tax.

At the start of the 20th century, Lizzie Magie, of the United States, dreamt up what was first called The Landlord's Game.

It had roughly the same rules as the game we know today. Except that when it became obvious that the natural end of property markets is a monopoly for one and poverty for the rest, the players could opt for a second set of rules. A key feature of those new rules was a tax on the value of land. This tax was distributed between the players, lifting the wealth of all, rather than just one.

Tolstoy and Magie were not the only ones to embrace a land tax.

Demi-gods in the economists' pantheon, such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo, have extolled the virtues of what has been coined "the perfect tax''.

It even seems to do the impossible, garnering support from opposite ends of economics' philosophical spectrum.

Free market proponent Milton Friedman and globalisation critic Joseph Stiglitz both came out on the side of a land tax.

Examples of that cross-party accord can also be found in New Zealand.

DR Andrew Coleman is an economics lecturer at the University of Otago. He also works half-time for the previous Government's favourite policy research group, the Productivity Commission. He does make it clear, however, that he is speaking as an academic, not on behalf of the commission.

"From an efficiency point of view, land taxes are great,'' Dr Coleman says.

Unlike other things, land doesn't diminish even when you tax it repeatedly.

And land values, especially in urban areas, are influenced primarily by developments such as roads, internet fibre, proximity to schools and shops.

"It reflects everything other than what you [as the owner] do. So, it's the perfect thing to tax.''

Land tax also promotes equity, Dr Coleman says.

"Land is disproportionately owned by wealthy people. So, [through a land tax] you are getting higher income people, who own higher value land, paying higher taxes.''

Well to the left on the political spectrum, is Marxist economist Assoc Prof Brian Roper. He is also willing to give LVT a tick, albeit a qualified one.

"I would be cautiously supportive of a land tax,'' Prof Roper, of the University of Otago, says.

"I'm all for progressive taxes ... [and] this is progressive; it would act as a tax on unearned capital gains. But I suspect the devil would be in the detail.''

If almost everyone thinks a land value tax would be a good idea, why didn't the TWG tell the Government we needed it?

David Snell says it was probably up for discussion.

"I expect it is something the group will have looked at quite seriously as an option,'' Snell, who is Ernst & Young's New Zealand tax policy leader, says.

But he believes the TWG was always more likely to recommend a capital gains tax than a land tax.

The Government, while saying it wanted a more flexible and fair tax system, had already struck several taxes off the TWG menu. That included increasing the rates of GST, income tax or corporate tax.

Inheritance tax and capital gains tax on the family home was also a no-go zone.

A standalone, substantial land value tax, which would replace or reduce other taxes, would have been too radical, too difficult, Snell says.

"I would be surprised if Sir Michael's group is going to be that revolutionary. I think it would be a huge transitional shift, and a step too far to go there now.''

It is the same reason an inheritance tax was not on the agenda.

Prof Roper favours a graduated inheritance tax, with a substantial threshold, for its power to redistribute wealth.

"The wealth that people accrue should be due to their own efforts, not their forebears','' he says.

"In essence, the wealth accumulated by the wealthy is actually produced by workers ... A tax that targets that wealth ameliorates the way capitalism produces inequality.''

That's too radical an approach for this Labour-coalition Government.

But even if a dramatic reworking of our tax system is unlikely, there are respected voices saying an LVT is still worth having.

Dr Coleman says the arguments are there in favour of a capital gains tax.

He says we are out of step with other countries by not having a such a tax.

"My contention would be that we have a system that, inadvertently, probably isn't achieving equity goals nor efficiency goals.

"I suspect that's because of the way we don't tax income from property.''

But Dr Coleman says a land value tax is as important a tool as the capital gains tax.

"It has the potential to raise revenue far more consistently [than a capital gains tax],'' Dr Coleman says.

"You'd get a whole bunch of revenue that you could use to lower other taxes.''

Economics commentator Bernard Hickey has been talking about this for a while.

In 2016, he wrote that a 1% land tax on all property owners would raise $6.7 billion a year. That would allow a 5.5% cut in personal tax rates or a 10% GST rate, he said.

A couple of years later, Hickey is still certain it is a great idea.

The politics of it would be awkward, but not insurmountable, he says. And the benefits are obvious.

"It would finally send the right signals to investors, that capital gains are not completely tax free, that more productive and intensive use of land makes sense, that land banking does not make sense, and that investing in equipment, research and development would be as sensible as a gearing up to buy land.

"It would be the biggest leg up for first home buyers in a couple of generations.''

Dr Zbigniew Dumienski thinks Queenstown would be the ideal place to trial an LVT.

Dr Dumienski has a PhD in international political economy, from the University of Auckland, and teaches economics at Auckland University of Technology.

He believes Queenstown would be perfect because it is a town that is struggling with housing affordability, poverty and property speculation.

Local residents could even be exempted, targeting the tax to "intercept the outflow of rent and return it to local residents'', he says.

"Without finding a way of sharing the community-created land rents, no policy aimed at reducing inequality and poverty can hope to fully succeed.''

HANNAH Allan has been playing Monopoly under the forgotten, land tax rules for 20 minutes. The change is dramatic.

Mr Monopoly still has greater property wealth and a healthy bank balance. But Allan's property wealth has doubled and her cash-in-hand has grown six-fold.

She has landed on the high value properties a couple of times. But because a portion of her rent, a.k.a. land tax, has gone to the Public Treasury for redistribution, and because other taxes have been dropped, she has been able to not only survive but thrive.

Allan is surprised.

"It's made a bigger difference than I thought it would,'' she says.

"If there were more than two players, would the results be just as good?'' she wonders aloud.

Excellent question.

What if the entire population of Queenstown, or the whole of New Zealand, were playing?

What if, instead of a game, it was real life?

Comments

Most of the benefits of a land tax are lost if it doesn't apply to all land, i.e., include the family home. That's why the TWG didn't recommend it.

As for a capital gains tax, Andrew Coleman should know better — just because other countries do dumb things doesn't mean we should emulate them. Any benefits of such a tax will accrue almost entirely to valuers and accountants while taxpayers will face huge bureaucratic costs.

So, you've spent your life working hard, raising a family, paying off the house and saving as best you can for your retirement years.

In the mean time the property you bought and now own continues to grown in value but your income has decreased.

CGT or LVT, either way, where does the money come from to pay this tax?

When I bought my first house it was just after the oil shocks of the 70's and interest rates were 18% and climbing. Unemployment was high and the government had it's finger in nearly everything.

Australia and Canada have CGT and they also face the same housing affordability issue. The US, France, Germany to name a few, do not.

So what is the difference?

Take a mortgage in NZ, Aus, CA you are liable. Not able to pay, sell at a lose, not their problem. They force the money out of you all the way to bankruptcy.

You carry the risk of earning the money and the market!

In the US etc, the bank carries the risk.

That is why we had the GFC. They got too gready, ignored risk and went broke.

If banks carried the risk in NZ, property prices would level, bringing stability.