Otago, Akaroa, Marlborough, Golden Bay, the West Coast, the Southern Lakes and back to Dunedin. Once upon a time, the South Island road trip was a carefree affair punctuated by the odd mix tape and occasional stops for, in no particular order, pies and petrol.

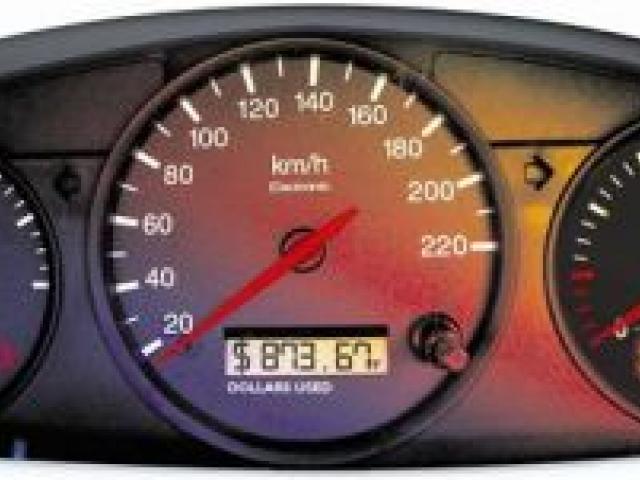

These days, the pies are best avoided, in the interests of the midriff, and the fumes that swirl and shimmer from the petrol pump's curved proboscis are simply a sensory reminder of how far one can't go on 20, 30, 40 bucks worth of gas.

It's a mindset that seems to be spreading: the Ministry of Economic Development's Domestic Travel Survey, which polls the spending and travel patterns of 15,000 New Zealanders, showed a decline in domestic travel in the year to December 2010, including a 3.8% reduction in overnight trips and a 6.5% decrease in day trips.

Dr Roger Wigglesworth, director of tourism, events and consumer affairs at the ministry, says the rising cost of fuel and the GST increase may have played a part in the reduction in travel.

Those 2010 results follow 2008's Domestic Travel Survey, which showed overnight trips had reduced by 2.2% and day trips by 12.5% on the previous year, in part a reaction to the record petrol price of $2.19 a litre of 91 octane set in July 2008.

Oil prices have risen about 25% since the start of this year, resulting in a 10% rise in the cost of petrol and a 20% hike in diesel. As of Thursday this week, prices in Otago hovered between $2.188 and $2.269 per litre of 91 octane (further away from the main centres the price is higher).

Based on calculations provided by the website www.fuelsaver.govt.nz, driving 10,000km (a yearly figure based on daily trips around town and some occasional, slightly longer weekend journeys) in my 1.6-litre manual Nissan Pulsar at $2.239 per litre of 91 octane (the price at some Alexandra pumps) would cost $1750; that's 17.5c per kilometre, meaning that 4km round trip to the supermarket costs roughly 70c.

Let's round it up to $1 to account for the stop-start nature of such a trip and the hill on the way back home. That one loaf of bread, or two-litre bottle of milk - often the reason for such a trip - starts to look more expensive than it already is.

A Parliamentary Library research paper published late last year, "The Next Oil Shock", describes oil demand as "inelastic" - that is, consumers cannot quickly find alternatives to oil. Forced to pay more not only for fuel but also for products that need oil for their manufacture and transportation, consumers have little alternative but to cut down on other expenditure.

The impact on a household's spending power is significant, according to Shamubeel Eaqub, New Zealand Institute of Economic Research principal economist.

He says mid-2010 figures revealed 68% of an average weekly household's spending was on necessities (food, fuel, mortgage repayments, rent, electricity, insurances, etc); thus, when fuel and food prices rise, discretionary spending on items such as televisions, furniture and appliances goes down.

"For example, in 2008, retail spending per person was virtually unchanged from the previous year. But within this, food and fuel spending rose very sharply (4.4% and 15.6% respectively). This badly affected other spending, particularly large-ticket items.

"There is also a confidence impact. Spikes in fuel prices, especially when in tandem with food prices, tend to sap confidence and willingness to spend, by both households and businesses," Mr Eaqub says.

"The issue is really quite important. Households could face a period of significant misery. We have the increase in food prices, fuel prices, a reduction in interest income, which is partly offset by reduction in mortgage payments. All up, I reckon the average household is worse off by $17 per week, even with the recent [Reserve Bank] interest rate cut."

Consumers will, over time, change their habits, he says, but that is not straightforward.

Old habits can be hard to break. Sarah Todd, pro-vice-chancellor (International) at the University of Otago and a professor of marketing, says the latest round of fuel-price rises might prompt people to review their driving habits, but significant, lasting change will take some time.

"You might get some people who try something short-term but that doesn't necessarily mean their behaviour is going to change.

"That's probably what we saw in 2008 when petrol prices last spiked. There was anecdotal evidence that petrol consumption went down over that time, but that doesn't mean attitudes towards driving cars changed," Prof Todd says.

Well-versed in the area of consumer behaviour trends, Prof Todd was co-author of the university Consumer Research Group's 2005-06 consumer lifestyles segmentation study. The fifth major survey of its type carried out by the group since 1979, it included questions about people's transport habits.

"Where we really saw it being different was in cities like Wellington, where there were very good alternatives to driving or where parking was impossible. If people don't see public transport to be at least as convenient - if not more so - than driving a car, it is going to be extremely difficult to get them to change their behaviour."

Deciding not to drive to Oamaru, Invercargill or further afield could be a relatively easy decision to make. Calculate the distance, apply the cost of petrol and, hey presto, suddenly that overnighter or weekend away looks pretty pricey. Such spending is discretionary, easier to defer or drop than those routine trips during the week.

"There is a price driver but there is also that convenience factor," Prof Todd says.

"A lot of people might drive to work and their car sits there all day, but they are also dropping off kids to school on the way to work, all those other things, so you are actually asking for a more significant change than just leaving the car at home.

"Many people will struggle to see what they can do about it.

"There have been things like the AA and other organisations giving tips on ways to cut your fuel use, such as stopping short trips where you use a lot of petrol. But a lot of those short trips are ingrained in people's lives. They are actually the hard ones to stop."

Green Party transport spokesman Gareth Hughes laments our reliance on oil.

"Oil is such a huge part of our economy. When it comes to our transport, we are 99.9% dependent on oil to move our products to market and to get to work," he commented earlier this week by phone from Wellington.

"The situation we are in at present is not an accident. It has come about by deliberate planning by both local and central government and investment in roads and motorways."

Mr Hughes points to the Government's $11 billion "roads of national significance" programme. Announced in 2009 by Transport Minister Steven Joyce, it is part of a 10-year state highway network plan to reduce congestion, improve safety and support economic growth in New Zealand.

"When you build a new motorway, more people use it. It will increase our reliance on oil for freight and the use of cars to get to work and for leisure.

"We are one of the few countries that doesn't have a plan to reduce our reliance on oil ... all around the world, from militaries to businesses to insurance companies to central governments, they've all started planning to reduce their dependence on oil.

"In New Zealand, as a response to the oil shocks of the 1970s, we have quite comprehensive supply disruption plans - stuff like car-less days and lowering the speed limit. All that legislation is sitting there waiting to be enacted in an emergency, but we've got no oil dependency reduction plans."

Research released by Colmar Brunton in August last year found 72% of New Zealanders wanted the Government to prepare for future oil-price rises by investing in alternative fuels and public transport.

Those polled were informed that the Government expects oil prices to rise steadily in the future as cheaper, easy-to-reach oil supplies decline around the world, and that increased oil production in New Zealand will have no impact on this trend because the price is fixed to international oil prices. Just because there is drilling off the Otago Coast, does not mean petrol will be cheaper in St Kilda.

Significantly, that study was conducted a month after the Government announced its draft energy strategy, which maintained a target of achieving 90% of energy production from renewable fuels by 2025 while placing a new accent on the exploration and development of fossil fuels.

Organisations including the International Energy Agency and the United States military have warned another supply crunch is likely to occur soon after 2012.

Closer to home, the Dunedin City Council last year commissioned a "Peak Oil Vulnerability Analysis Report", which included surveys on residents' travel habits, private fuel consumption and vehicle dependence and the effect of petrol prices.

Consultants recommended Dunedin should work on the following objectives:

• Plan to reduce oil consumption by 50% by 2050.

• Encourage central city lifestyle development and urban villages, accessed by 100km of cycleways and pedestrian zones and served by public transport.

• Improve the average vehicle fleet efficiency to 5 litres per 100km by 2030.

• Audit and track fuel use in all sectors, organisations and households and develop action plans.

• Build an electric trolley bus system spanning at least 50km.

On the latter subject, the report claims converting to electric buses or trolleys would lead to a direct reduction in fuel demand and provide an increasingly affordable alternative when fuel price spikes hurt.

However, given previous studies have shown it would cost about $8 million to have light rail from the Dunedin Botanic Garden to the Exchange area, such a plan would not be cheap. And, critics ask, who foots the bill?

Which brings us to the crux of the matter: when it comes to oil (and the alternatives), how deep are we prepared to dig?

PEDAL POWER

Ben Williscroft, a senior lecturer in marketing at the University of Otago and a keen cyclist, is old enough to recall the oil shocks of the 1970s. Living in Christchurch at the time, he witnessed a rapid rise in cyclists - "flocks of them, including people in suits".

Co-author of a 2007 study on ways to improve conditions for cyclists, Dr Williscroft found the cost of petrol to be the second most important factor governing whether people drove or biked, behind drivers' attitudes to cyclists.

"When we sent out our surveys, we put in a petrol price that at the time seemed excessively high - but it has almost been realised now. But the impact of that was still less than the perception of drivers' attitudes to cyclists. From our research, people are going to avoid cycling until they think that other drivers will treat them with respect.

"We need that critical mass of cyclists, which will make it acceptable and safe. We know from overseas research that if the number of cyclists as a proportion doubles - say from 1% to 2% - the safety factor almost doubles as well," says Dr Williscroft.

"I'm sure there is a tipping point: whether it is $2.20 or $2.50 or $3 per litre. We don't know what it is, but it will be a point at which enough people say, 'I have to cut down on my driving' or 'I have to start car-pooling'."

GOING EASY ON THE GAS

HARRIET GEOGHEGAN

Otago University Students Association president

If I didn't have a job as well as studying, I don't think I would drive.

I live in Northeast Valley. Now that I have a job I can afford to drive. I guess if I'm going to take a weekend away anywhere I'd have to think about whether I could afford that.

I think there are a lot of students who would like to drive but know that it is really expensive. Even though I've got a job I've also got a bike and I'll be using that a lot more if prices keep going up.

KATH TUNA

Secretary of Grey Power Otago

Well, I'm noticing it now. I come from Pine Hill to the office in South Dunedin. We are talking about Shank's pony, I think. I've done it before. However, I also have to do a lot of messages.

I have a small car but I've noticed the cost. I fill the tank up periodically and it just goes, down, down, down.

I do think about day trips but I make sure I've got enough money to go there. I don't trip away very much.

DAVE STEDMAN

Owner of Dunedin bookbinding business Dutybound

I'm only a five-minute drive down the motorway from Caversham to work so it's not too bad, but it's when I start going across town to drop my daughter off that I start burning up gas. In fact, we've just bought a diesel car and we are finding we are using half as much fuel and at a lower price. So whenever we decide to go anywhere, we jump in the diesel wagon.

I'm a guy who likes to go and have a drive just because I feel like it, but now I don't do that. Whereas I used to think about going to Outram for a coffee, just for a drive, I have to stop and say 'actually, that's going to cost me big dollars in petrol'. In the past I wouldn't have even thought about it. It's probably one of the most obvious household costs nowadays.