It’s approaching midnight on a warm November Friday in central Dunedin.

Usually there would be preened and boisterous queues four-deep and a few metres long outside several of the most popular inner-city bars and clubs.

But tonight, the bouncers have time on their hands. The streets are abnormally orderly.

Here, on the cusp of the 20th anniversary of New Zealand lowering the drinking age, the city’s watering holes are flapping in the doldrums, caught between the late-spring, mass migration of 20,000 tertiary students and the yet-to-be-felt winds of Christmas carousing.

Most weeks of the year, at this time of night, the Octagon and its arteries would be throbbing with intoxicating, youthful excitement fuelled by intoxicated, excited youth.

Unlikely to be found among that throng are three young adults who this evening are at the head of a short queue waiting to ascend the stairs to Carousel Bar, just off the Octagon, on lower Stuart St.

Ella Montgomery is belatedly celebrating the end of her first year of tertiary study. Accompanying her are Courtney Keith-Bourke and Sam Moore.

None of the three students were born when, 20 years ago tomorrow, New Zealand lowered the legal drinking age from 20 to 18.

Her two friends are driving and have work in the morning. Typically, they would drink once a fortnight. Tonight they are strictly on the OJ.

They are happy to describe themselves and their restrained drinking habits as unusual among their peers.

"You have the one percent right here," Keith-Bourke says.

Most young adults they know drink regularly and heavily.

The trio would not, however, support an increase in the legal drinking age.

"It’s good as it is," Moore says. His companions nod their agreement.

But are they right?

Twenty years of 18+ drinking could be the ideal opportunity to reassess and perhaps reverse that decision, restoring the legal drinking age to 20.

Throw a few statistics at it and the case for lifting the drinking age can be made.

Researchers have taken a look at what happened in the months after December 1, 1999. It reveals those who predicted the end of civilisation as we knew it can clearly show the change caused greater harm to young people. More young people had alcohol-related vehicle crashes and more ended up in hospital emergency departments after the drinking age was reduced.

Prof Kypros Kypri published a study in the American Journal of Health in 2006, comparing alcohol-involved crashes before and after the New Zealand law change.

Among men aged 15 to 19, the ratio of the alcohol-involved crash rate after the law change to the period before was 13% larger, relative to 20-24 year olds, Prof Kypri, who is based at the University of Newcastle, Australia, says. Among young women, the equivalent ratios were 51% larger for 18 to 19 year olds and 24% larger for 15 to 17 year olds.

In plain English: "Significantly more alcohol-involved crashes occurred among 15- to 19-year olds than would have occurred had the alcohol purchase age not been lowered," Prof Kypri says.

A Ministry of Health (MOH) survey of New Zealanders, released this month, points to a youth drinking culture still bent on regular benders.

The annual Health of New Zealand Survey reveals more than 20% of young adults are regularly drinking heavily.

"More than one in five young adults are now drinking heavily at least weekly," an Alcohol Healthwatch spokesperson who released the data a fortnight ago said.

"Our drinking culture is continuing to move in the wrong direction."

The only logical conclusion, therefore, would appear to be to pass a law lifting the legal drinking age back to 20. Or higher.

But, that would be to miss the detail, the complexity, the real picture and, consequently, the best way forward.

Here’s the warp and woof.

Surprisingly, since the new millennium, fewer young people in New Zealand are drinking.

In fact, between 2007 and 2012 there was a significant decrease in the number of secondary school pupils consuming alcohol.

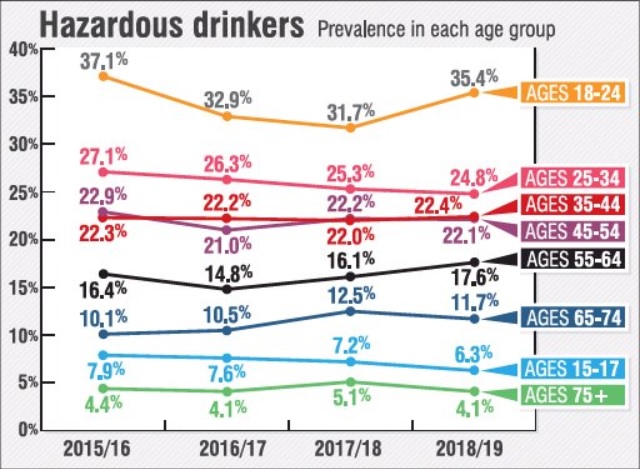

That downward trend includes hazardous drinkers. And it has persisted. Four years ago, 7.9% of all 15 to 17 year olds in New Zealand — 15,000 high schoolers — were hazardous drinkers, according to the MOH. That has declined each year, to reach 6.3%, or 13,000 youngsters, this year.

This is part of a global sea change.

Many studies reveal that in developed countries, young people aged 15 to 24 have been drinking less alcohol since 2000.

That is not to say the picture is all rosy.

Worldwide, including here, there are still young people drinking to excess.

In New Zealand, in 2019, one in five young people are heavy drinkers.

Globally there is a socio-economic component to hazardous drinking trends. Some of the most disadvantaged subgroups of youth haven’t followed the downward course.

Here too, it has been shown, for instance, that decreases in the number of under-16 females drinking were significantly greater among higher income households.

If you are poor, male or Maori, you have a higher than average chance of being a heavy drinking young person.

That, though, does not take away from this astonishing, widespread, long-term decline in youth drinking.

The reasons for the decline are not yet well understood.

There are plenty of theories.

Some argue it is linked to more time spent on social media; others that it’s about young people being more health conscious, or parents being more vigilant, or a statistical reflection of greater ethnic diversity.

Whatever the reason, the end-point is the same — more young people are making smarter choices about their drinking.

And less drinking is a subset of a wider cultural shift. Young people are also smoking less, abusing other substances less and having less early sex. More of them are choosing not to engage in risky behaviours, across the board.

Beth Lynch and her friends typify this new attitude to drinking.

The Dunedin year 13 pupil says she has never bothered with alcohol because it has "never seemed necessary".

"I’ve seen how the [drinking] culture operates," the savvy 17-year-old says.

"I don’t need it in order to have a good time."

Cameron Monteath, who can legally have a drink, says he does not even think about it.

"I don’t tend to be around people who drink," he says.

"I had parents who promoted a sensible way of approaching alcohol. It contributed to that way of thinking."

Monteath can foresee, however, a possible adjustment.

"That could easily change at university," he adds.

Interesting comment. Because, despite this swing to global youth enlightenment, there is one age group subset, in one country, that is bucking the trend — 18 to 24 year olds in New Zealand.

Four years ago, more than 37% of Kiwis aged 18 to 24 were classified as hazardous drinkers. Those 178,000 people — including binge drinkers, who drink more than six drinks on one occasion at least weekly — dropped to 157,000 the following year and shrank to 151,000 the next.

But in this past year it has surged back. There are now 158,000 young people aged 18 to 24 drinking regularly and heavily.

It is a puzzle and a worry, Dr Nicki Jackson says.

"We would have hoped they would have maintained the cultural change once they had reached the legal drinking age, but we haven’t seen those big drop offs," Dr Jackson, executive director of research and lobby charity Alcohol Healthwatch, says.

"In latest data, the 18 to 24 year olds have increased their frequency of heavy drinking."

What can be done to stem the flow of teetotaling youngsters becoming weekly bingers?

Several things, Dr Jackson says.

It is curious that the age to which drinking was lowered also marks the boundary beyond which problem youth drinking has increased. But, apparently, there is no direct correlation. Several countries have legal drinking ages similar to New Zealand but haven’t experienced the increase in hazardous drinking seen here.

So, while raising the drinking age is on Dr Jackson’s agenda, it is not in the top three on her to-do list.

"The drinking age is still an issue. We had our opportunity in 2011 to put the age back up and MPs decided against it."

A key to tackling the harm alcohol does to young lives is reducing the advertising and sponsorship of alcohol, Dr Jackson says.

"In New Zealand, 50% of all persons who go on to abuse alcohol or become dependent on alcohol do so by the age of 20, and 70% by the age of 25," she says.

"Alcohol advertising is a key driver of consumption in these age groups."

Dr Jackson says successive governments have been dragging their feet on this for at least a decade.

"We’ve had the Law Commission[report Alcohol in Our Lives], the Ministerial Forum on Alcohol Advertising and Sponsorship and now, this year, the [Government] Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction, all calling for action on alcohol advertising and sponsorship.

"But we still have an environment saturated with alcohol advertising."

In addition to advertising, Dr Jackson says ready access to alcohol is an important factor.

Compared with other countries, it is easy in New Zealand to get alcohol from sellers that are not bars and restaurants.

Up to 80% of all alcohol purchased in New Zealand is from off-licences — bottle stores and supermarkets.

"We are a country that predominately buys cheap alcohol and consumes it in unsupervised settings," Dr Jackson says.

"That is absolutely something that needs to change."

But it is the price of alcohol that most worries and angers Dr Jackson.

"Alcohol is our most harmful drug, and it is far more affordable today than ever before."

Many alcohol products are sold for less than $1per standard drink. Research shows this fuels heavy and frequent drinking, especially among young adults.

The opposite is also true, she says.

"Price is one of the biggest drivers of consumption we continue to not address.

"It is also the strongest evidence we have for reducing consumption.

"First and foremost the price needs to change."

Dr Jackson draws breath and sums up.

"Cheap alcohol, the high numbers of alcohol outlets in our neighbourhoods and the saturation of alcohol advertising and sponsorship is preventing our country from making a meaningful difference to our mental health and wellbeing."

He believes things will not improve unless there is "a significant change in attitude across our communities".

Dr Clark says the Government is investing $56 million over four years to bolster access to alcohol and other drug addiction services, including detoxification services and residential care.

At the top of the cliff, he says MOH staff are still developing plans in response to alcohol recommendations that came from the mental health and addiction inquiry.

Perhaps signalling what that plan might include, Dr Clark specifies "the inquiry’s recommendations on alcohol include making changes to our approach to the sale and supply of alcohol".

Sipping their soft drinks and iced-coffee, the three Dunedin high schoolers have words of caution and advice for the Minister and his policy advisers if they want to develop effective strategies.

Twenty years on, the teenagers are not in favour of raising the drinking age.

Lynch says a supermarket chain’s move this year to restrict energy drink sales to those aged over 16 should be a lesson to the Government in how not to deal with young people and alcohol.

"I know 15 year olds who are furious just because they are no longer allowed to buy the energy drinks. So, they get others to buy them for them," she says.

"I think the same would happen with alcohol."

Do not demonise alcohol, Souquet warns.

Harm should be tackled through education, he says.

"Help people to understand it without glorifying it."

This could include requiring film-makers to change how alcohol is presented in movies and advertising.

Monteath nods.

Yes, he says, a change of culture is needed.

"Especially in Dunedin where there is such a drinking culture, so it’s easy to get in to it."