A quarter of a century ago, Dunedin City Council elected members were told they should put aside $3million a year to renew the city's ageing water pipes. There was no consistent follow-through. It is now estimated that by 2029 it will cost ratepayers $35million a year to get the job done.

Farsighted. Adjective. Having or showing imagination or foresight. Prudent, discerning, judicious, canny.

In 1995, Murray Petrie was an engineer working in the DCC water department. The city's drinking water was graded "E".

"It was pretty bad," says Petrie, who has recently retired after a 42-year engineering career, including three decades at the city council.

"It was highly coloured water from up at Deep Stream. It was only chlorinated. It smelt a lot and tasted terrible."

Ironically, captains docking passenger liners at Port Chalmers in those early days of the cruise ship boom were commenting on the excellent quality of the water with which they could refill tanks.

"Now if you asked the people in Port Chalmers about the quality of their water, they would have said it's terrible," Petrie recalls.

"Their water was going through nearly 100-year-old pipes that hadn't been maintained, had bio-film and everything else. So, their water was disgusting."

City water engineer at the time, Nigel Harwood, conducted a strategic study of the issue. He insisted that water treatment was not the only problem; that reticulation, supply, the whole of the city's water infrastructure, needed attention. It was Harwood, Petrie says, who told councillors they needed to be spending $3million a year to sort things before they got worse.

"It was a good, farsighted decision - had it been maintained," Petrie says.

"You do look at the planning and wonder about some of the decisions.

"There have been a lot of decisions made that now will be very costly."

That is just one example, from one local government body.

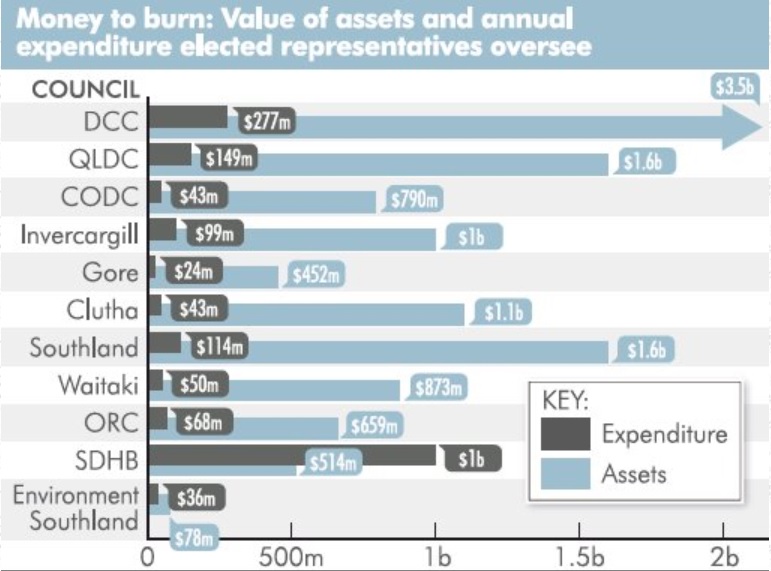

South of the Waitaki River there are two regional councils, nine territorial authorities, one district health board, three licensing trusts and dozens of community boards comprised of hundreds of elected representatives of the people. Every three years, all positions are up for grabs. In less than a fortnight, when postal voting papers start to be delivered throughout the South, cumulatively they will bear the names of almost 500 candidates vying for 304 positions. Almost 60% will not previously have been an elected representative of the seat they are seeking. Whether incumbent or newbie, they will have widely differing backgrounds, opinions, levels of experience. And together they will be managing assets with a combined value of more than $12billion and handling budgets that add up to almost $2billion a year of spending.

Whether it's infrastructure renewal, climate change and the future of South Dunedin, managing debt, cancer treatment waiting times, air quality, the housing crisis, growing inequality, Maori representation, water rights, water quality, airport locations or the Dunedin Hospital build ... there is no shortage of important, far-reaching decisions to get right.

As Local Government New Zealand (LGNZ) principal policy adviser Mike Reid puts it: "Elected members are responsible for the direction of councils that control billions of dollars' worth of community owned assets, so it's vital that they have good decision-making and governance skills".

But how capable are our elected representatives of making these crucial calls?

How well trained are they in the skills of quality decision-making?

Jinty MacTavish was a young influential councillor during her two terms on the Dunedin City Council. Since she chose not to stand for re-election, in 2016, she has been a DCC Second Generation District Plan commissioner and a kakapo recovery team ranger on Whenua Hou (Codfish) Island.

MacTavish believes there has been an improvement in decision-making compared with when she was first elected in 2010. Key to that was the development of the council's strategic framework, which gave "a really solid framework for holistic decision-making".

"Before council adopted its strategic framework, my observation is that decision-making seemed to be reactive and ad-hoc," MacTavish says.

"There did not seem to be a cohesive vision, and councillors did not seem to be considering the intersection of different issues, or all the potential ramifications of each decision."

To help their elected representatives, most councils run their own induction programmes to try to ensure knowledge and skills are up to speed.

DCC civic team leader Sharon Bodeker, for example, says the council runs a "comprehensive" induction programme, including decision-making, as well as optional additional ongoing training.

An Otago Regional Council spokesman says that organisation also has an induction programme and offers optional courses, including a Making Good Decisions Programme organised by the Ministry for the Environment.

In addition, LGNZ has induction and training modules that many councils offer to their members.

Ryan Jones, however, sees some gaping holes. Jones was the youngest community board member in New Zealand when elected to Dunedin's West Harbour Community Board, in 2016. During that time he has also been on the LGNZ community board national executive. He will graduate in December with a master's degree in politics and is stepping down to work "in the public housing space".

"Too often in local government, the training is pretty sub-par, because councils do not allocate sufficient resources for training and professional development," Jones says.

"That's not just a Dunedin problem; that's generally the case for all councils across the country."

He says the public is not happy with the state of local government.

"Satisfaction levels for local government are even lower than voter turnout.

"I think better training for our members is a big part of answering that issue."

If Jones sees skills gaps, Petrie sees some of the negative impacts that have come from mis-handled decisions around council tables.

By way of example, he returns to the issue of water infrastructure renewal. It was too easy, he says, for successive councils to defer the work in order to cut costs. The result; "Now we're landed with quite a large infrastructure replacement cost".

That seems to be putting it rather mildly.

What had been $3million a year in 1995 had, by 2012, become a projection that $26million a year would need to be spent for the decade from 2025. By 2016, the government auditor was warning the DCC's "three waters" (drinking, storm and waste water) renewal spending was $60million behind schedule. Those chickens are now coming home to roost - $37 of every $100 of Dunedin ratepayers' money goes to three-waters spending. But they also appear to be being shooed into the future. The latest forecast is that three-waters renewal expenditure will need to be $35million a year for 16 years from 2029 and then just under $30million a year for a further 20 years.

"Most of our long-term decisions are the same sort of thinking as `What will I have for breakfast?', rather than `This needs a lot of thought. I'd better really think about this one'."

What, then, is solid, long-term decision-making?

Petrie is keen on the approach of best-selling author Steven Johnson, presented in his 2018 book Farsighted: How we make the decisions that matter most.

In the book, Johnson presents what he calls the "full spectrum" analysis process that he says is used by successful decision-makers. That process involves mapping (identifying variables and plotting possible paths), predicting (using a variety of techniques to explore likely outcomes of the possible paths) and deciding (aided by a scenario-scoring approach based on maximising value and minimising harm).

MacTavish says good decision making relies on "really good information flow between council and the community".

"Good decision-making happens when councillors are able to take a holistic, strategic approach to their decisions, considering environmental, social, cultural and economic wellbeing together.

"[It] also requires that councillors have the information, the organisational support and the moral courage to assess and address any given issue within a longer-term vision for the city - a vision that is developed democratically and held collectively."

That, however, does not mean elected representatives will not make mistakes - and they need to be allowed to make them, Justine Gilliland says.

Gilliland is chief executive of Venture Taranaki, the province's regional development agency. She spearheaded Taranaki 2050, the first local government initiative worldwide to co-create, with its community, a roadmap for a transition to a low-carbon economy.

Gilliland does not want to mention bad decisions she has witnessed, but has some personal observations on how elected representatives can make important decisions well.

But ultimately, says Gilliland, the way to learn how to make decisions is to make them.

"We are a bit quick to jump on people when they make a mistake.

"The best way we learn is by making mistakes and then learning from them."

Making important decisions is exactly what our hundreds of elected representatives will have to do, once the dust settles after polling day on October 12.

Jones says resourcing the development of good decision-making skills is "fundamental if we are to make the big decisions which are required of us in the near future".

"As a member of the community board executive committee, I have really stressed the need for better training for our members.

"I hope there will be more success in the next triennium to allocate more resources towards training and professional development."

Twenty-first century issues are "messy and complex" and will require bold decisions, MacTavish says.

"There are so many huge issues that require urgent attention, and all of them rub up against each other in difficult ways.

"For me, climate change and rising inequality are the two stand-out issues, both locally and nationally. They are cross-cutting problems that affect every aspect of society, and that will have significant ramifications for this wonderful place we call home over the coming decades.

"While local government can not solve them alone, bold, proactive and creative local responses are absolutely critical in ensuring we do solve them."

Petrie also looks at the daunting task elected representatives face. He wonders how effectively they are going to manage.

"How are they going to make their minds up, and where are they going to get the information from?

"These people need to ... be told how difficult it is to make good long-term decisions; that there are ways to make them but that it takes a long time, you have to get a lot of information and a lot of people working on it and have true consultation with a diversity of input.

"In a lot of cases the decisions you originally think you might go to, something completely left-field comes out and that's the way you'll go.

"We need to have these people think about this a bit more; about how do they make decisions."

Giving more power to the people

"Political donations are badly regulated, official information laws are being circumvented, and opportunities for deep citizen engagement with politics are limited," Rashbrooke says.

In a report Bridges Both Ways : Transforming the openness of New Zealand government Rashbrooke says the country needs to join the global push for greater openness.

"As the legal philosopher Jeremy Waldron has argued, `There is such a degree of substantive disagreement among us about the merits of particular proposals ... that any claim that law makes on our respect and our compliance is going to have to be rooted in the fairness and openness of the democratic process by which it was made'."

In the 2017 report, Rashbrooke sets out five options for making New Zealand's government "profoundly more open to public scrutiny, accountability and input".

•Participatory budgeting: Building on successful models overseas, local councils could set aside 10% (or more) of their annual budget to be decided directly by citizens. Councils would work with residents throughout the year, holding multiple meetings at neighbourhood and ward level, as a build-up to a major end-of-year meeting in which residents would vote on how to allocate the funds. Such processes are increasingly used overseas, and have proved highly effective in engaging citizens.

•Crowd-sourced Bills: Also copying successful models overseas, the public could be allowed to submit proposals for Bills via a secure online platform, giving detailed reasons and evidence to support their proposed law. Those receiving enough signatures - more than 35,000, say - would have to be debated and voted on by Parliament, having first gone through the Office of the Clerk to be drafted and improved. This would open up law-making to direct public involvement, while retaining vital checks and balances.

•A "Public Opinion" Budget: At the start of each year a group of representatively chosen citizens, advised by experts, could draw up a rough budget, indicating areas of funding priority - such as whether they want to see more or less spending in broadly defined categories such as health, education and defence - and what tax increases or reductions would be needed in consequence. This would help inform official budget decisions and allow public scrutiny of where the official budget diverges from citizens' expressed preferences.

•A "Korero Politics" Day: Two to three months before every general election, there could be a public holiday dedicated to discussing politics and the coming vote. This "Korero Politics" Day would be marked by community events, town hall meetings, festivals that combine music and politics, and other gatherings designed to foster discussion. This would underline the importance of politics, give people time and space to think about issues, and encourage a more reflective citizenship.

•Democratising party funding: To improve the integrity of political party funding, donations could be capped at $1500 per person per year, as is done in Canada. The shortfall could then be made up with democratic public funding: a $20 "electoral funding voucher" giving every citizen a small amount of money to give to the political party of their choice, once every electoral cycle. This could create a strong incentive for parties to engage with the public, while spreading influence more widely.