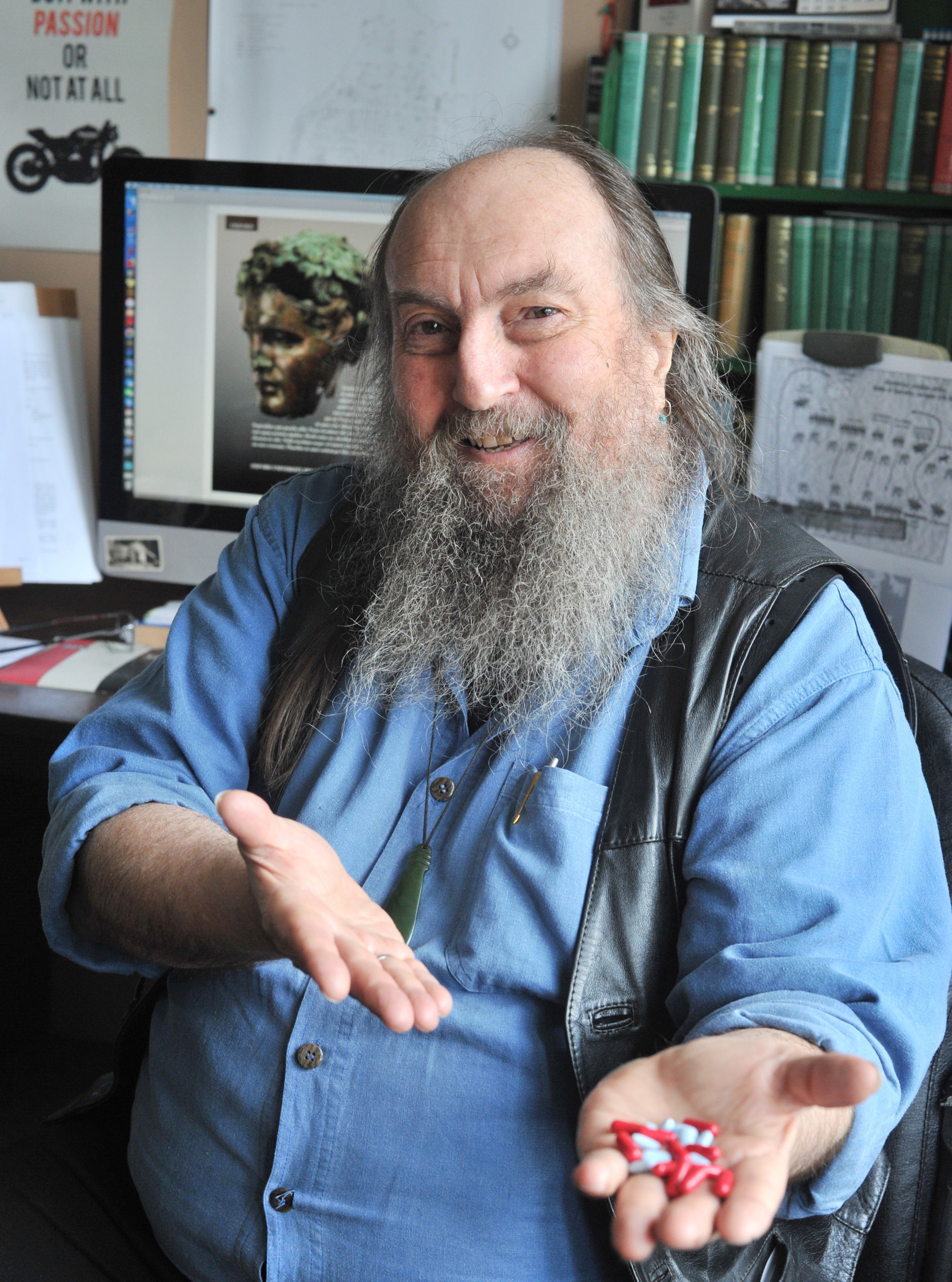

There is something discombobulating about Pat Wheatley.

Sitting there in bulging denim shirt and black leather vest, a broad smile on his bearded face, he is the epitome of the congenial, ageing biker.

But the walls of his St Leonards, Dunedin, home office are lined with textbooks and two enormous maps of the ancient Mediterranean world. On the desktop computer screen is the front cover of his new tome on Alexander the Great. Signs consistent with being an associate professor of ancient history at the University of Otago.

His back-story, like his speech, is an exuberant mishmash of low and high-brow. Raised in the Canterbury high country, he has been a truck driver and a historian, a wandering hippy and an accomplished academic.

"I went to university for a brief moment when I left school," he says with a smile.

"But I chucked it in and went travelling and did a lot of jobs ... And then, at the age of 36, I went back to university."

Prof Wheatley is a maverick.

And that, apparently, is what is required to help rid New Zealand of the stigma and scourge of hepatitis C.

Two years ago, Prof Wheatley had no idea that for decades he had been host to the virus that was slowly, steadily killing him.

He was still carrying a full-time academic workload; lecturing, researching, publishing articles and supervising students. Looking back, however, he knows all was not well.

"I now realise things can creep up on you," Prof Wheatley says.

"You think it's normal to be not feeling so good, to be a bit foggy in the brain.

"Your general wellbeing is a bit down."

Unseen, his liver was scarred to the point of cirrhosis by its fight with the HepC virus that was stealing his body's energy in order to attack him. Unwittingly, 64-year-old Prof Wheatley was well on his way to liver cancer and an untimely death.

"Then, I got a new doctor. A young bloke, of Indian descent, Rahul.

"And I'll tell you what, this guy saved my life."

HepC is a virus that is spread by blood-to-blood contact. You can only catch it if the blood in your body comes into contact with blood contaminated with HepC. Injecting drugs, getting tattooed with unsterilised equipment and rough sex are all the stereotypical "risk factors".

So, too, is having had a blood transfusion pre-1992.

It was during the 1980s that the mysterious non-Hep A and non-Hep B virus was properly identified and labelled "C". Until blood banks then began screening donors in the early-1990s, contaminated blood was being given to unsuspecting patients worldwide.

For up to 20% of those who contract HepC, their body's immune system will successfully get rid of it.

But for most, the internal viral war will slowly cause fibrosis (scarring) of their liver. Two to four decades down the track, it will have caused enough tissue thickening, cell degeneration and inflammation to earn the label cirrhosis.

Symptoms of HepC can take decades to make themselves felt. They include a sore liver, some nausea, depression and fatigue.

Fatigue is a big issue because the HepC virus digs right in to the mitochondria - the body's cellular-level energy factories - steals the energy and uses it to replicate itself, repeatedly, causing inflammation, cell death and tissue damage.

Cognitive dysfunction, a "mind fog", is another progressive and debilitating symptom.

A further 15 years on, untreated, 60% of those with cirrhosis will have developed liver cancer, Margaret Fraser, a hepatology clinical nurse specialist with the Southern District Health Board (SDHB), says.

"If not diagnosed they will get decompensated liver disease and die," Fraser, who has been treating HepC patients for 17 years, says.

Globally, it is estimated that 71million people have chronic HepC. In New Zealand the estimate is 50,000, half of whom do not know they have it.

That is a lot of people unaware they are already making down-payments to the ferryman; unaware an almost-guaranteed cure is now available; and who, if untreated, will precipitate skyrocketing health costs in a few years, Dr Steven Johnson says.

"In about 10 or 20 years, eight or ten thousand people are going to show up with hepatocellular carcinoma or liver failure," the consultant gastroenterologist at the SDHB says.

"So, that will be a huge burden on the health system.

"If we can find those people before that happens we save a lot of money."

New Zealand has signed up to the World Health Organisation's goal of eliminating HepC worldwide by 2030. That makes it important to understand the multiple reasons why so many people are infected but undiagnosed.

Firstly, only 10% of people with HepC have symptoms soon after they contract it. So they do not necessarily relate symptoms that show up, possibly decades later, with the infection event and therefore with the virus.

Secondly, most of those who were obviously at risk have been found, tested and treated.

"All the low-hanging fruit has been picked," Dr Johnson says.

That leaves the 25,000 who don't fit the risk profile.

"We've got to find these people," Fraser says.

"They are the living, working well, who somewhere in their past have been infected with HepC."

"I have a patient who was the first responder to a car accident where there was a lot of blood," Fraser says.

"He reckons that was his only risk factor for getting HepC."

General Practitioners (GPs) under-estimating the prevalence of HepC is another reason so many cases remain undetected.

People with HepC visit their local doctor 30% more often than the general population, Dr Johnson says. But too often, HepC is not considered a possible cause.

Fraser had a female patient who was treated by her GP for a decade for "viral malaise" without working out it was HepC.

Dr Johnson did a nationwide survey of GPs in New Zealand.

"Nearly all the GPs underestimated the number of patients in their practice that might have HepC by between two and tenfold."

The terrifying side-effects, and the 10% to 60% cure rate, of earlier HepC treatments has also made some people reluctant to get tested or, even if they knew they had the disease, get treated.

"It wasn't until this year that we've got a treatment that works, that has minimal side effects and has a 99% cure rate," Fraser says.

"It was a treatment that you `Went to hell to get well'.

"People heard stories and so they'd never want to come forward for treatment because it was so hideous.

"Some people had to give up their jobs. It was just awful."

The largest obstacle, however, is stigma.

The stigma surrounding HepC is "huge", Fraser says.

"People perceive those with HepC to be dirty."

Fraser has numerous examples.

One patient had given Fraser permission to use his name and details in a presentation she made yesterday at the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners national conference being held in Dunedin this weekend. But the ostracisim he experienced after telling workmates he had been cured of HepC made him withdraw his consent.

Another patient thought telling his boss that he was being treated for HepC was the right thing to do. Not long after, in a workplace restructuring, he was let go.

It is not right, Fraser says forcefully.

"When people get the 'flu we don't ask how they got it.

"We've been so fixated on how people got HepC. It's just a virus. We just need to get on and treat them."

HepC stigma is still so strong that, of the more than 150 people treated for the virus at Dunedin Hospital during the past 18 months, only one is willing to talk about it; only one feels able to take an open stand to help reduce the stigma and encourage others to get tested - Prof Wheatley.

As with so many others who have had the virus, he is not sure when he contracted HepC.

It could have been somewhere along the famed Hippie Trail stretching from Southeast Asia to Europe.

"It was amazing. But the trouble is, along the way I may have picked up HepC somewhere."

Or it could have been as a result of a motorbike accident.

"I've knocked myself around a bit. I'm a biker. You fall off from time to time and break things."

The most likely contender is a bad crash he had in 1972, in which his friend was killed and Prof Wheatley ended up in hospital, badly injured and needing a blood transfusion.

But he does know when he got cured.

The first time his new doctor suggested a HepC blood test, Prof Wheatley did nothing. Six months later, his GP repeated the request and he complied. The presence of HepC antibodies meant a follow-up test was needed to see if he was actually infected.

His doctor delivered the bad news. Treatment began immediately. It was December, 2016.

The side-effects were nasty but the drug, Viekira Pak, seemed to be doing the job. By the five-week mark the viral load, the measure of how much HepC was present, had dropped from 1.4million to just 27.

But unknown to Prof Wheatley and his health team, the virus had mutated and was no longer susceptible to the drug. When he was tested at the end of the 12-week treatment, the viral load was a whopping 2.4-million.

Prof Wheatley went ahead with research leave in 2017, spending the year in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom.

By the time he and his wife returned he was feeling "pretty shit-house".

No other suitable drugs were being funded by the Government's drug-buying agency, Pharmac. Fraser suggested he could join a Tasmania-based HepC drug buyers group importing Epclusa, a potentially effective drug from India.

For $3000, Dr Wheatley got a 24-week course of pills.

"There were some pretty tough drugs ... Last year was a prick of a thing ... But this treatment, mate, it smashed it."

By the middle of last year, he was cured of HepC.

Dr Wheatley's treatment ordeal, however, can now be consigned to history.

When Dr Johnson started treating HepC patients 25 years ago, doctors were happy if they got a 50% cure rate, but rarely achieved that. Maverit has a 99% cure rate.

For most people, three tablets a day with food for eight weeks does the trick.

Everyone got side-effects with earlier treatments. Between 3% and 10% get side-effects with Maviret.

The $25,000 cost of treatment is fully funded by Pharmac.

Fraser says she used to hate her job.

"All these people over the last few years who have been dying of liver cancer. It was just so depressing."

Now, she and Dr Johnson are excited by the prospect of finding the Southern portion of the country's missing 25,000 and getting them cured.

Nationwide, since Maviret was made available, 2054 people have been treated. About 170 of those are in the SDHB region.

The effect of being cured is dramatic.

"If you can treat the HepC before the liver develops cirrohsis, the liver can repair itself, and the patients' `all-cause morbidity' will return to normal; there won't be any lasting impact," Fraser says.

Just as impressive is the restoration of cognitive function.

"I had a guy who started treatment at the same time he started polytech," she says.

"Within a month they said, you're not in the right class, we've got to put you up a class."

Looking back, Prof Wheatley recognises a similar transformation.

"Over summer I completed a very long-term project I've been working on for 15 years."

It is his book on Alexander the Great, co-written with one of his former students.

"To get this to the publisher on time we worked like 15 hours a day for a couple of months.

"I know [with HepC] it would have been practically impossible to maintain such an intense period of focus."

Now the race is on to find everyone else.

The country's medical laboratories have been doing a "look back" programme to identify people with HepC who did not get, or did not complete, treatment, and track them down.

Dr Johnson is working towards getting approval for a simple HepC test, based on mouth swabs or finger prick blood samples, that can give a result in 20 minutes and can be administered by GPs or other community-based health professionals.

"The key to these 25,000 people running around out there is to identify them," Dr Johnson says.

"Treatment is now not the issue, it's easy. But finding these people is tough because no-one wants to talk about it."

Get tested, that is Prof Wheatley's message.

"The sole reason I agreed to this interview ... is maybe some good would come of it.

"If you think for any reason whatever, even a very faint one, you might be at risk, just get a blood test. It's as easy as anything."

Yesterday, Sunday, July 28, was World Hepatitis Day.