The sun provides all the energy we'll ever need. We just need to plug into its current output, writes Colin Campbell-Hunt.

One of the great things about working in a university research centre is the steady flow of international visitors and the stimulating ideas they bring with them. The University of Otago's Centre for Sustainability is a real magnet for these people, hosting no less than eight international visitors this year, among them Dr Martin Hohmann-Mariott from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Martin is interested in photosynthesis, the process by which plants convert energy from the sun to create living matter - matter that in time decays into all of the various fossil fuels; coal, oil, and gas. I am very grateful for his guidance in writing this column.

In fact, photosynthesis captures only a tiny fraction of the energy that bombards our planet from the sun. Taking a 75 watt light bulb as a bundle of energy we all know, the sun radiates something more than 2000 trillion light-bulb equivalents to the earth. (A trillion is a big number: 1 followed by 12 zeros. Famously, if I were to pay you $1 every second, it would take me about 32,000 years to pay you $1 trillion). If we were to give the sun a watt-rating, it would come in at 162,000 trillion watts. Of all of that energy, only 90 trillion watts are stored by plants and algae in biomass through photosynthesis. And yet, more than 90% of the energy we now use to power our lives comes to us via this very limited channel and we have yet to learn how to tap into the far, far greater flows of energy that surround us.

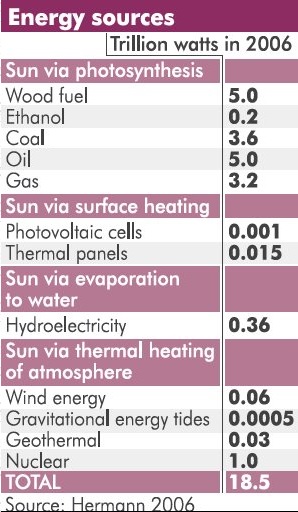

A 2006 paper by Weston Hermann in the journal Energy offers what I would call an accounting of the flows of energy through our planet.

As of 2006, human energy use added up to 18.5 trillion watts. Where does it come from? A big contribution does indeed come from biomass by burning living trees for heating - about 5 trillion watts - no wonder the world's forests are shrinking. We also gain another 0.2 trillion by producing ethanol from biomass.

If we were to look to the very limited flow of 90 million watts via photosynthesis to support all of our energy needs, that would use up about 20% of all of the energy stored in biomass across the whole planet. And we need plants for other reasons too; food, fibres and buildings.

There are of course many sources of energy apart from photosynthesis and plants. Roughly a quarter of the sun's radiative energy is absorbed as heat in the atmosphere, driving wind and waves. Another quarter hits the earth's surface, driving evaporation, clouds, rain and rivers. We humans have learned to make some use of these energy sources. In 2006, one-third of a trillion (360 billion) watts came from hydroelectricity, 60 billion from wind, and 16 billion from photovoltaic cells and thermal panels. And there are other sources of energy apart from the sun: gravitational forces create tides and drive rivers; the earth itself is a source of thermal energy. In 2006, geothermal energy was contributing 30 billion watts of energy.

Of course, these renewable sources of energy have been greatly expanded since 2006 - wind energy by more than 50% - but together they probably now come to no more than half a trillion watts. Last but not least is nuclear power, providing 1 trillion watts of energy in 2006.

But the energy source that has really made our lifestyles possible is the 12 trillion watts of energy we dig out of the ground in the form of coal, gas and oil: energy that has taken plants millennia to put there. In accounting terms, we are financing two-thirds of our annual energy spending from past energy savings. We have been lazy and done the easiest and cheapest thing and just dug up carbon to burn. Getting fossil fuels out of our lives will require us to find a much more sustainable balance between energy coming in and our energy use.

Hermann's paper also begs some tantalising questions about where we might get the energy we believe we need. For example, winds around the planet produce 870 trillion watts of energy, from which we were producing just 60 billion watts in 2006, perhaps 90 billion watts now. A phenomenal 43,000 trillion watts of the sun's energy heats the surface of the planet, from which we garner only one-hundredth of one trillion watts. Hermann is careful to point out that our current use of these energy sources is limited by current technologies and economic feasibility (which means they are more expensive than the cheap and dangerous use of fossil fuels).

So the bottom line of this accounting is that we have barely dipped our toes into the hugely powerful flows of energy that hum around us. If there are limits on our use of energy they are not ones imposed by the planet, but by our technological imagination and our determination not to ruin the only planet we have.

Colin Campbell-Hunt is an emeritus professor at the CSAFE Centre for Sustainability, University of Otago. Each week in this column, one of a panel of writers addresses issues of sustainability.