High-flying women in science are in Dunedin for the New Zealand International Science Festival. Bruce Munro talks to influential coder Ally Watson and aeronautics professor Karen Willcox about life in male-dominated worlds and how to create a better one.

Paying close attention is just something you do when listening to Ally Watson. It's that working-class Scottish accent, filtered through four years of living in Melbourne. It can be tricky.

For several minutes, she repeatedly uses a word that, after some hesitation, is written on the journalist notepad as "ghettoes''.

"One thing we are trying to do with the ghettoes ...''

"We're building a classroom for [something] ghettoes ...''

Then the penny drops. Not "ghettoes'', but "ghurrils''. Girls.

But, it is not just the accent. Listening to the enthusiastic information technology (IT) entrepreneur is a compelling thought-roller-coaster, regularly twisting and dropping into surprising, revealing territory. It is best to hold on tight and listen up.

She is talking about the predominance of white middle-class males in the IT industry.

What comes out of the profession is not surprising considering what goes into it, Watson says.

"I guess what you end up with when you have a privileged workforce is Uber and apps for ... laundry services. You are not really tackling important problems. Because, to be honest, maybe the workforce isn't thinking about those problems.''

Watson is among several high-flying women on the bill for the 10-day, 2018 New Zealand International Science Festival, which opened yesterday, in Dunedin.

Last year, Watson was named one of Australia's nine most influential female entrepreneurs. She is in town to talk about her highly acclaimed social enterprise, Code Like a Girl, and explain why it is vital we encourage more girls into this sector.

It is a long way, however, and not just geographically, from where Watson was raised in the plateaued, 1990s, industrial township of Airdrie, between Glasgow and Edinburgh.

She was the youngest of four girls, raised by a solo mum. The Spice Girls were her role models. Becoming an artist was the dream. Nothing, really, that would hint at a future as a computer programmer.

But in 2007, having twice missed out on art school, she spotted an advertisement for a software engineering course.

"I thought, well, why not.''

The first time Watson walked into a computer science class she was shocked by how few girls there were.

"But that didn't deter me. It was difficult being in a minority as well as not having grown up with tech - it was a real learning curve - but I enjoyed the challenge.''

And when she realised design and psychology were important ingredients in successful software engineering, the enjoyment deepened.

"Once I figured out my niche and that I had a passion in that area, I fell in love with it.''

Whether Watson was already an outsider or her experience in the male-dominated IT industry channelled her towards that persona is moot. Either way, she has embraced the role.

"The tattoos started when I was 23,'' says Watson, who is colourfully tattooed on her arms and shoulders with emblems of the natural world.

"I see my tattoos, like my clothes, as part of who I am and a way of expressing my personality. I like challenging stereotypes and stigmas.''

Not that being a woman in tech has been an easy or painless road, she admits.

"For me, it was the subtle things,'' she says.

You start a new job. You're terrified already. You just want everyone to like you and you want to make some friends. But it is harder because you don't know anything about football and you don't drink much beer. So, finding common ground can be difficult.

"Where it may take a man a day to build those bonds, it might take me several months.''

She also found it difficult to speak up in meetings.

"You're in a room full of men. They are comfortable in their space because they've been there longer and there's more of them.''

The competitiveness in programmer culture was also alien.

"I prefer to be in a learning environment that is nurturing and welcoming, instead of a real sense of bragging and competition and scoffing at people for things they don't know.''

Feeling like an outsider sometimes stopped her putting herself forward for projects and dented her confidence.

"I also found I had managers who didn't know how to interact with me and would feel a bit awkward around me ... So, I would find myself excluded from a lot of casual, and sometimes important, conversation.''

It is a worldwide issue. In the United States, estimates put the number of women in professional IT jobs at about 25%. In New Zealand, less than one computer programmer in five is female.

There is no question that in virtually every industry women still have ground to gain in the employment equality stakes.

Recent weeks have provided two glaring examples.

In mid-June, Equal Opportunities Commissioner Jackie Blue blew the whistle on her colleague, State Services Commissioner Peter Hughes.

Hughes had announced the new chief executives of five public service sectors. All were existing public service chief executives who had been reshuffled without the positions being advertised. All were men.

That came a week after the head of global aviation said only a man could do his job.

Akbar Al Baker, who is Qatar Airways chief executive, made the comments in Sydney when he was appointed chairman of the International Air Transport Association.

Asked what could be done to tackle the lack of women in Middle East aviation, Al Baker replied this was not the case at Qatar Airways. He then added, "Of course, it has to be led by a man, because it is a very challenging position.''

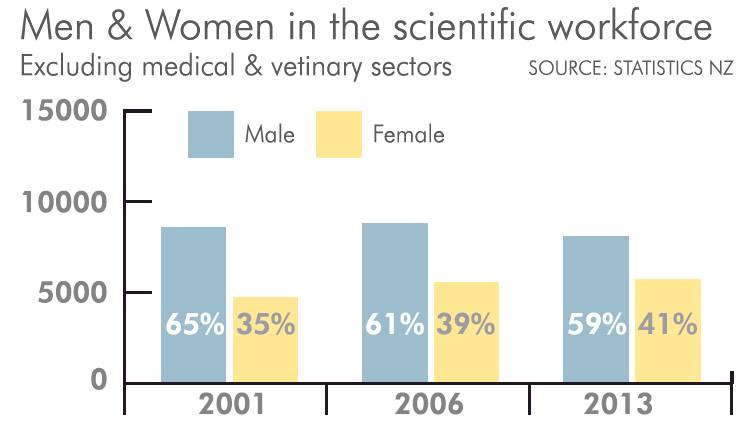

In the scientific workforce in New Zealand, women are closing the gap, slowly.

Statistics New Zealand figures show that since the new millennium, women have increased their share of the non-medical, non-veterinary, scientific workforce by six percentage points. They now occupy 41% of jobs such as physicist, mathematician, geologist, computer programmer and horticultural scientist.

Things are more positive in the total scientific workforce, which includes medical and veterinary professions, where women have been employed in greater numbers for longer. Women have grown from 55% of the total scientific workforce in 2001 to 60% in 2013.

But in non-medical scientific jobs, based on the rate of increase since 2001, it will be 2032 before women are on an equal footing.

Sharing the spotlight with Watson at the New Zealand International Science Festival will be expatriate New Zealander Prof Karen Willcox.

Another successful woman in science, Prof Willcox says that while her own story illustrates the power of reaching for the impossible, specific steps must be taken to encourage more girls into science.

Prof Willcox left New Zealand for the United States 24 years ago, propelled by the dream of becoming this country's first astronaut.

"Certainly, that was the goal that led me in to aerospace engineering and led me to the US,'' Prof Watson says on the phone from Austin, Texas.

"I made it to the final round of astronaut selection in 2009 and then again in 2013. In 2013, I know I came super close, but didn't quite make it.''

That dream has now slipped beyond reach. At 46, Prof Willcox is too old to go into space. That realisation has not been easy.

"The hard part is to have come so close and to have not made it, and to wonder what I could have done differently.''

But good things have come from it, she says.

"I feel I had this dream that was completely impossible. Following that dream to the US, it was the first time I had left New Zealand. Without that passion, it is hard to believe I would have taken that big step.''

It was in the US that she met her husband, a South African academic, when both were playing for Massachusetts Institute of Technology rugby teams. They now have two children.

And taking the leap, although it has not landed her on the moon, has led to an exciting, fulfilling career.

"I love being a professor, and I love my research and I love teaching.

"I think it is a perfect blend of research and teaching, working with young people and industry and government.''

A hint that her career is stratospheric comes in a most unusual way. During the interview, the phone goes silent, without disconnecting, right at the moment Prof Willcox is talking about advanced military technologies. Was someone listening in, concerned she might divulge a state secret or two?

She is now professor of aeronautics and astronautics and co-director of the Centre for Computational Engineering at MIT. She is also on a plethora of MIT and US government panels.

Her research, much of it for the United States Air Force, is at the intersection of aerospace engineering and esoteric mathematics.

"It takes a long time to develop the technologies to the point they are really well understood and you can get the sort of performance and safety that is essential,'' she explains.

On the way there, aircraft designers and engineers are faced with myriad crucial questions.

"The work that I do is to create computer models and computer methods that help designers identify those uncertainties and analyse their effects so they can ultimately make good decisions.''

Deep pools of knowledge about aircraft, physics, probability and statistics all have to be available to be drawn on and their waters combined in innovative ways.

"I love it. I really enjoy the part that's about aircraft and aircraft design, working with Boeing and the air force on actual vehicles. But I also really enjoy the abstract mathematics.''

To reach this point, Prof Willcox says she has had some great support.

"For the most part, in terms of professors and mentors, I feel I've been incredibly lucky.

"I've had people who have helped me and made sure I've had great opportunities in my career.''

As a woman in science, however, there have certainly been times when she has felt out of place, "like you don't belong''.

"That obviously happened as a student, when the numbers [of women] were low. But it still happens now.

"Even now, when I am very senior and well-versed in the field, I still go to industry meetings where there are one or two women in a room of more than 100.

"I don't think anybody likes to feel different. We've come a long way, but we still have a long way to go, that's for sure.''

Prof Willcox believes a better job needs to be done of helping young people, and especially young women, understand what a career in science in general, and technology and engineering in particular, can mean.

"I think there is a widespread belief that engineers are people who fix things. Engineering is so much more than that. Engineers create and design things that make the world a better place for all of us.

"That understanding is important for all young people. But it is particularly important for young women who may not be so excited by the prospect of fixing something mechanical but who like the idea of making the world a better place.''

That is surprisingly close to Watson's vision for the power of computer code and her social enterprise Code Like a Girl.

After several years working as a software engineer in boutique, design and marketing agencies, and feeling the need to connect with more female programmers, Watson advertised what she thought would be a small gathering of colleagues.

One hundred women in the Melbourne IT industry turned up. Then, as word got out, more women wanting to get into IT started turning up.

Eighteen months ago, Watson quit her day job and started Code Like a Girl. The social enterprise runs workshops and camps for girls and women wanting to get into the world of tech. It also runs code-based events for corporate clients, has a job platform and hooks talented young tech-savvy women up with businesses looking for interns. Workshops and events have been held in Adelaide and Sydney, as well as Melbourne.

Some of the enterprise's profits will be ploughed into pop-up coding workshops for girls in disadvantaged parts of Australia. A trial has already been held, with good success.

The overall aim, Watson says, is to change the shape of tomorrow.

"I think there is a huge problem with technology. Predominantly it is white, male, privileged programmers.

"A big thing we are trying to tackle at Code Like a Girl is not just continuing that churning out of more privileged people getting into technology.''

The future is being built by coders, she says. As the Internet Of Things becomes more pervasive, it is their world we will have to live in, for better or worse.

"We believe women should be equal creators in building the future.''

Women techies might bring something other than Tinder to the table. Disadvantaged girls empowered to code might tackle problems more pressing than pizza delivery apps.

Women in science

Opportunities to hear some of the New Zealand International Science Festival’s special women guests this week.

• Monday, July 9, 11am to 2pm.

A rocket-making workshop with a difference; your teacher is professor of aeronautics and astronautics Karen Willcox. For children 8+ years.

• Monday, July 9, 5pm.

A pizza Q&A dinner with space experts Karen Willcox, Oleg Abramov and Sian Cleaver. Aimed at high school-aged

girls, but all welcome.

• Monday, July 9, 6pm.

US professor of aeronautics and astronautics Karen Willcox joins UK space systems engineer Sian Cleaver and Planetary Science Institute scientist Dr Oleg Abramov for an evening on the latest advances in space technology.

• Tuesday, July 10, 11am to 2pm.

A rocket-making workshop with a difference; your teacher is professor of aeronautics and astronautics Karen Willcox. For children 8+ years.

• Tuesday, July 10, 2pm to 3.30pm.

A coding workshop for 8 to 16-year-olds led by Ally Watson, of Code Like a Girl. Sold out, sorry.

• Tuesday, July 10, 6pm to 7.30pm.

Hear from Ally Watson, CEO of Code Like A Girl, and Dunedin’s own Kylie Robinson, of Igtimi, about what it means to be a woman in tech and why it’s important to encourage more girls into this often male-dominated sector. Hosted by Helen Anderson, QSO.

• Wednesday, July 11, 4.45pm to 6pm.

A chat with Sian Cleaver, principal mission systems engineer at Airbus UK, who is working on the design and development of future European Space Agency exploration missions. The talk will be about her work and about achieving gender balance in STEM sectors.

• Friday, July 13, 6pm to 8pm.

Enjoy a three-course feast while hearing from award-winning film-maker Kristin Pichaske about conspiracy theories and what leads rational people to believe irrational things.

• During the next nine days, the 2018 New Zealand International Science Festival brings together more than 20 global science leaders and dozens of other local and national practitioners for 230 science-focused events spanning a dozen disciplines in 24 locations throughout Dunedin.

• For more information, more speakers and ticketing details, visit www.scifest.org.nz.