First the Americans came for British period drama. Now the Brits are getting their mitts on Italy’s heritage. In 2020, the US producer Shonda Rhimes sexed-up Regency England with lusty intrigue, soapy storylines and orchestral covers of pop hits to create Netflix’s smash-hit Bridgerton. This year, British screenwriters Benji Walters and Richard Warlow (The Serpent) and director Tom Shankland (SAS Rogue Heroes) are collaborating with the streamer on a bit of pop cultural colonisation of their own.

You can see why they would want to: The Leopard — the trio’s adaptation of Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s seminal novel, set in 1860s Sicily — is sumptuous, sensuous, emotionally tempestuous and full of nice food; all qualities UK-based costume drama tends to lack. But this sweaty, steamy series is far more than a treat for the senses. Behind the frills and the romantic thrills — at the centre of the action is a captivating young love triangle — is a socio-historically insightful tale of an elite clan’s descent into obsolescence.

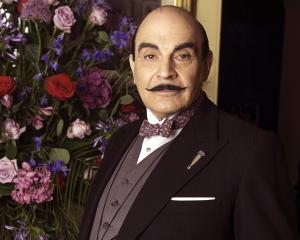

The eponymous Leopard is Don Fabrizio, the Prince of Salina, who got his nickname from the big cat on his family crest. Played by a whiskered Kim Rossi Stuart (the cast is Italian and the show is subtitled), the prince must reluctantly adapt to survive after Garibaldi’s redshirt army wrests control of Sicily from the House of Bourbon as part of their quest to unify Italy. Fabrizio is — obviously — against the revolution; he fears for the safety of his family and the erosion of his wealth and influence. Yet his beloved nephew Tancredi isn’t so shortsighted. He joins the redshirts, not just because he’s a daredevil — he can see which way the wind is blowing. “If we want everything to stay as it is,” he tells his baffled uncle, “then everything must change.”

The Leopard is a meditation on mortality. Fabrizio realises he is ageing out of relevance just as his way of life is becoming a thing of the past. The regime change does not spell annihilation for the nobility, but does require them to learn a different kind of dance: collaboration with the new proletarian overlords and the burgeoning middle class. Until now, our protagonist has been the last word in male, moneyed privilege. His entitlement means he thinks little of having his priest accompany him on a trip to visit his lover (challenged on his infidelity, his excuse is that he has never seen his pious wife’s navel) but all of a sudden he has to sweet talk some upstart colonel in order to visit his country pile. The crumbling of status and power is one of fiction’s most compelling archetypes, and The Leopard elicits its hypnotic combination of schadenfreude and sympathy.

That country pile is the site of the show’s other major storyline. Tancredi has been kind-of courting his cousin Concetta, Fabrizio’s wholesome and besotted daughter. But soon there is a rival for his affections in the form of the newly wealthy mayor’s daughter, Angelica (Deva Cassel, daughter of Monica Bellucci and Vincent Cassel), who seems to have been bred for the task of seducing him.

Before The Leopard was a six-part Netflix show, it was a three-hour film starring Burt Lancaster, released five years after the novel was posthumously published in 1958. On paper, the two are not that different; there are many overlaps between dialogue and scenes. Rossi Stuart’s prince is colder but less cruel, funny and pervy than Lancaster’s, while Saul Nanni’s Tancredi somehow rivals Alain Delon for renegade heart-throb status. In fact, this cast has a notable advantage: Rossi Stuart and Nanni are both Italian; in what must have been a confusing shoot, Lancaster spoke his lines in English while Delon spoke French, then both were dubbed in Italian.

Yet Luchino Visconti’s movie was also steeped in a magical strangeness: a gothic gloom, a frenzy to the family’s Catholicism and a dangerously febrile feeling courses through every scene. The film’s stunning arrangement of bodies is a sight to behold, whether on Palermo’s city centre turned battlefield or the dancefloor in its famous 45-minute ballroom scene. Despite all its aesthetic loveliness, this new Leopard feels visually prosaic in comparison; a pretty streaming series rather than a veritable work of art.

The advantage is that this version is more coherent and watchable, without ever being sugary or simplistic. The great story is intact, posing its evergreen questions — when it comes to tradition, where is the line between evolution and extinction? When it comes to power, where does pragmatism bleed into surrender? — for a new audience. The Leopard’s sultry good looks will make you swoon, but this beady-eyed examination of how the ruling classes navigate regime change has plenty of substance too.

• The Leopard is now available streaming on Netflix. — The Guardian