As we waited for his band Shellac to play night one of their two-night residency at the Port Chalmers venue, he approached our group of three very middle-aged men and asked if we were the radio interviewers he was waiting for.

On being told no he shot back: "Sorry, you white guys all look the same to me," before vanishing. Soon after he was on stage tearing the place up in a memorable set which can still be found on the internet.

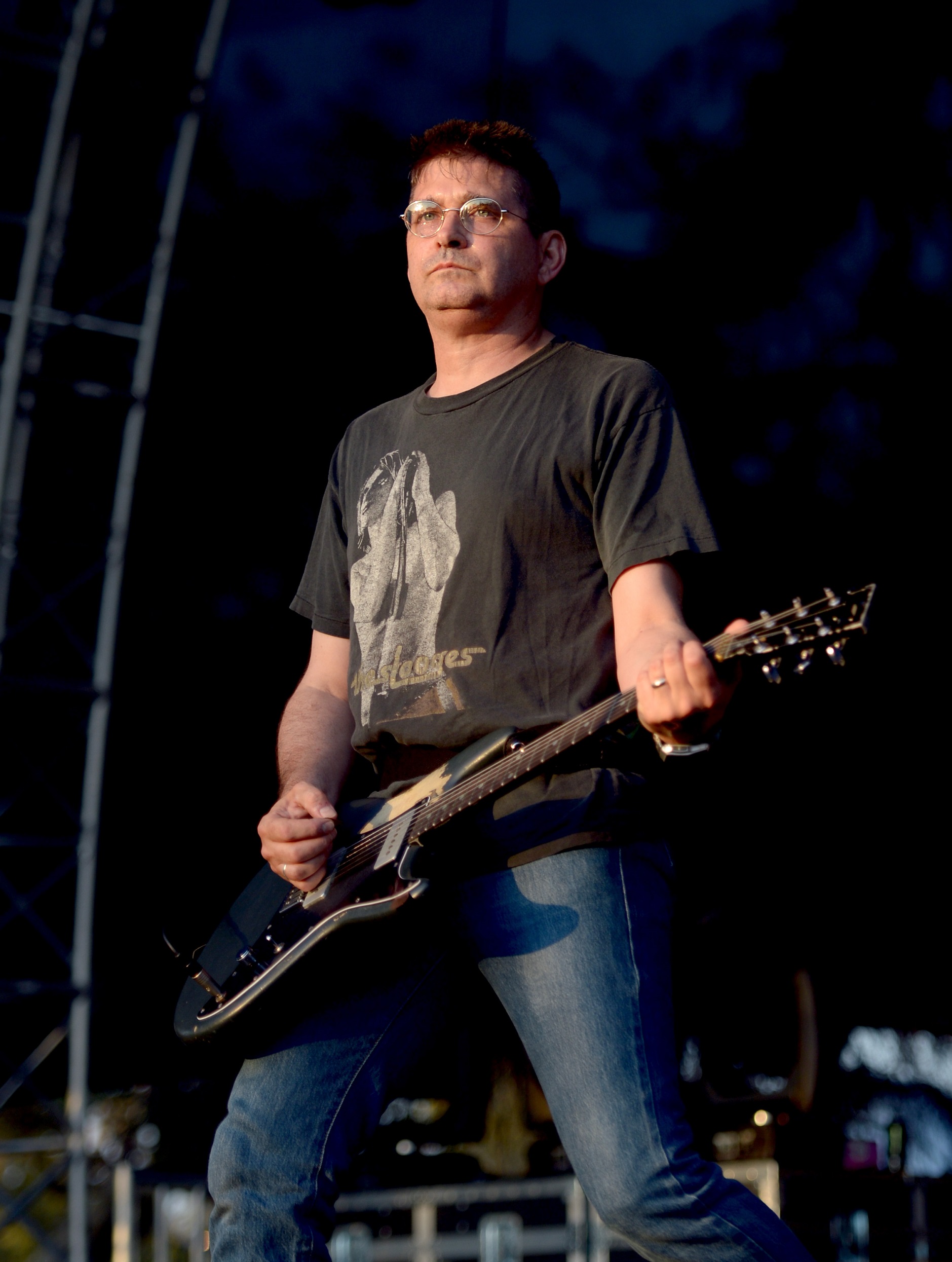

California-born, Montana-raised and Chicago-native Steve Albini thrived on challenging people, both verbally with a mouth which kept him constantly in trouble, and musically with a CV both as a player and engineer on albums which demanded a reaction from the listener.

As a journalism major at Northwestern University, Albini became a leading light in the city’s punk/alternative scene, fronting the brutal assault on the ears that was Big Black. The band’s brief career spawned two albums, the second and best being the utterly uncompromising Songs About F...ing. A controversy magnet, Albini’s next band was called Rapeman: inspired by a manga comic of the same name, Albini later called the name choice "flippant and indefensible".

In 1988 Albini, who had been dabbling with sound engineering for some time, was paired with Boston band Pixies as producer — a term which Albini intensely disliked — on the band’s breakthrough record Surfer Rosa. Instantly hailed a classic, it made Albini someone who musicians — if not necessarily record companies, given his directness and contrariness — wanted to work with.

A year later Rapeman split and Albini went on to form his longest-lasting group, Shellac. More experimental and thoughtful than its predecessors, the noise-rock of Shellac stood the test of time. The trio released six acclaimed albums and was poised to release a seventh this year.

Albini combined working on records — his favoured credit was "Recorded by Steve Albini" — and touring with Shellac for the rest of his working life.

His mixing desk CV was incredible. While the most famous was Nirvana’s final album, In Utero, Albini also helmed records by P J Harvey, Mogwai, The Wedding Present, Slint, The Breeders, the Jesus Lizard, Godspeed You!, Black Emperor and Dirty Three.

In 2001 Albini hosted Dunedin band High Dependency Unit, which had supported Shellac on a New Zealand tour, in the US to record their album Fire Works. In another local connection, in March 2005 Albini spent three days recording and mixing the debut album of Dunedin’s Die! Die! Die!

"The recording part is the part that matters to me — that I’m making a document that records a piece of our culture, the life’s work of the musicians that are hiring me," Albini told The Guardian last year, when asked about some of the well-known and much-loved albums he’s recorded.

"I take that part very seriously. I want the music to outlive all of us."

Albini was a larger-than-life character, known for his forward-thinking, unapologetic irreverence, acerbic sense of humour and criticisms of the music industry’s exploitative practices — as detailed in his 1993 essay The Problem with Music, a piece whose world-weary cynicism has dated little.

With age he became an unlikely but highly skilled poker player, and also more inclined to be apologetic for his past indiscretions.

Steve Albini died from a heart attack on May 7 aged 61. At the time of his death, Albini’s band Shellac were preparing to tour their first new album in a decade, To All Trains. — Mike Houlahan, AP.