Discovering their mothers worked together in Dunedin and their grandmothers were friends has been a nice surprise for musicians Bridget Douglas and Al Fraser.

‘‘We only found out when we started this duo,’’ Fraser says.

Both musicians grew up in Dunedin but did not meet until many years later when they discovered how well their sounds came together.

It began back in 2018 when Fraser and Douglas performed part-time Otago Peninsula resident Dame Gillian Whitehead’s Hineraukatauri at Government House for the Arts Foundation Awards Ceremony at the request of Dame Gillian, who received an Arts Icon award that evening.

Hineraukatauri was the first piece written for Western flute and nga taonga puoro (a Maori musical instrument) in 1999. It was originally written for the late Richard Nunns, who saved many taonga puoro practices, and flautist Alexa Still — Douglas’ flute teacher at Victoria University.

‘‘At the time it was an unusual and different sound to create. Gillian was the perfect person to bring the instruments together as it brought both worlds together,’’ Douglas says.

In tribute to the piece that brought them together, they have included it on their recently released album Silver Stone Wood Bone.

‘‘When Al and I played that piece together we realised we loved the sound it made and we enjoyed working together and thought ‘wouldn’t it be great to have more than one piece to play, maybe a whole concert of music’.’’

So they talked to composers whose music they admired to create pieces for the instruments.

A mix of established and young composers were commissioned, with the help of Creative New Zealand funding — Rosie Langabeer, Briar Prastiti, John Psathas, Josiah Carr, and Gareth Farr — to each write a piece of between 5 and 10 minutes long.

‘‘We also wanted to think about younger, upcoming composers and we wanted to encourage the next generation. We think there is some incredible talent that deserves to be heard a lot more in the future,’’ Douglas said.

For Fraser, the project is one of a long line of collaborations as he further advances the use of nga taonga puoro, which he describes as a ‘‘revival art’’.

Originally studying jazz guitar in Wellington, Fraser was introduced to taonga puoro in his last year of study through a concert by Nunns and after completing study began researching and making his own taonga puoro instruments.

‘‘It was really how the voices gave me a direct musical connection to Aotearoa and its people and land and all its inhabitants — it has been a great way to learn about Aotearoa by making and playing in lots of different ways. There is always learning to be done.’’

Collaborations, like this one, help him extend his musicality in ways he does not regularly do.

‘‘I often work in a looser song formats, mostly with music I’ve written myself. This is different in that it is music composed by someone else so you really do need to stick to the programme, stick to the music, but there is also that element to play reasonably freely within those confines.’’

Overall, it is a stricter musicality than he is used to, and playing other people’s music is different again.

‘‘I’m getting these ideas from different musical minds and being told how to approach things which is giving me new ideas.’’

Douglas has found the experience of working with Fraser very liberating, having come from a classical music background — she is the section principal flute of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and teaches flute at the New Zealand School of Music, Te Koki.

‘‘This way, as Al says, makes you feel connected to land, our time and our place in a way. As much as I love playing Beethoven and Mozart, all those great composers, there is something really special about doing something that has been completely generated here in Aotearoa.

‘‘I can’t play the instruments Al plays, but I love the traditional flute I play can in some ways blend and weave in with those instruments Al plays that are made from things you find on the beach.’’

She also enjoys the ability to play music not so confined by the music’s direction.

‘‘We have more freedom to express the composers’ wishes in a way that they are different each time we play them.’’

It also enables Douglas to connect with a different type of audience than she might through a chamber or symphony orchestra classical concert.

‘‘I think I yearn to be a bit more down to earth, a bit more connected to real time, real place kind of stuff. It gives great balance of musical output, makes it more musically satisfying and a bit more whole.

Douglas says there is also an element of freedom in the way the instruments combine.

‘‘Al’s taonga puoro does not lend itself to traditional classical notation so for him it feels relatively structured but for me it’s the most freedom I’ve ever been allowed in a concert.’’

Fraser says each composition creates a ‘‘really unique sound world’’ which they are able to realise and honour.

Bringing together the two different worlds is good for both musicians as both gain from it.

Douglas says that musically they come at it from different angles.

‘‘I do love the fact that Al and I are in charge of our musical decisions and I don’t have to do what someone else tells me to do. We get to make all the calls while honouring what the composer’s written.’’

The pieces themselves are living pieces, so they can mutate and change over a series of performances, which is exciting for Douglas.

‘‘Being in charge of your own musical destiny is a great thing I certainly do not take for granted.’’

To ensure the works translated to recordings the pair brought in sound engineer Graham Kennedy whom they both knew, and hired out a small concert hall at Victoria University.

‘‘We had the best in New Zealand for that.’’

They found having performed the works at the Dunedin Festival of Arts and the Festival of Colour in Wanaka helped them prepare for the recording just a few days later.

‘‘It was great to have those live experiences behind us before we recorded. We’d lived with the pieces for a bit first which was great.’’

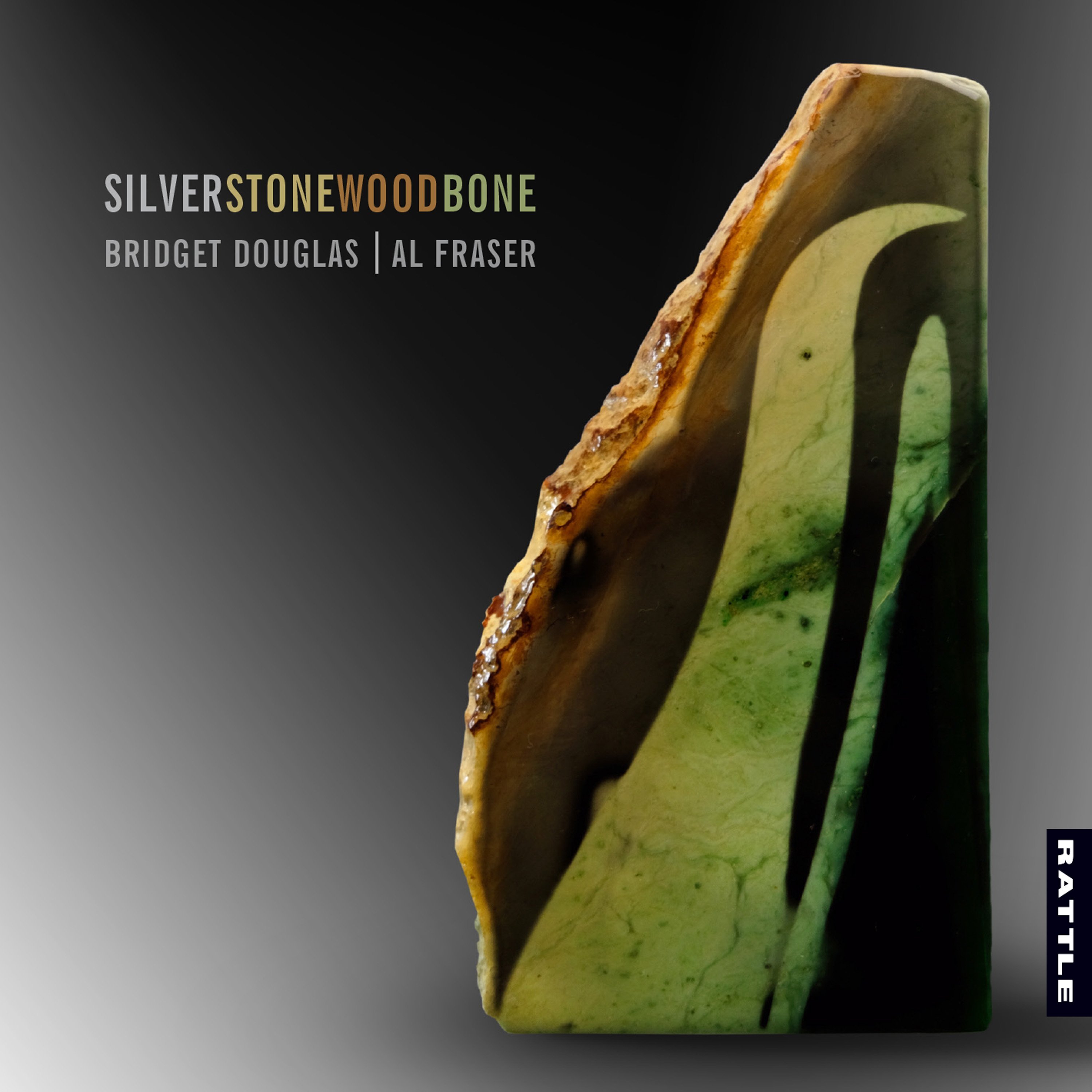

The pair are now touring the works, this time with a specially commissioned one-hour moving image artwork by University of Otago Frances Hodgkins fellow Bridget Reweti to accompany each of the pieces. Her work without skin and flesh also adorns the cover of the album.

‘‘They work really well together,’’ Douglas says.

Douglas and Fraser also have plans to perform at an international conference for composers next year, and both also play in STROMA, which will play one of Fraser’s works this month.

‘‘We want to keep playing as much as we can.’’

Fraser, who quit his day job just before the first Covid-19 lockdown hit, has found the demand for taonga puoro to be growing even with a knock-back from the pandemic.

‘‘Things have bounced back. I can keep playing as much as I can.’’

He is a prolific recording artist, having featured on seven Rattle releases since 2018: Shearwater Drift, Ponguru, Panthalassa, Mixed Messages, Nau Mai E Ka Hua, Exiles and his solo debut, Toitu Te Puoro.

‘‘Music is this magic thing — when you play it it disappears into the ether. So recording is a way of having a permanent record of music that would just vanish.’’

It is especially so with Fraser’s work which is different each time it is played and can involve different instruments being used.

‘‘Hopefully, the music will survive through the recordings. It will be something people can listen to.’’

For the recording, Fraser gave the composers recordings of instruments he uses so they could choose what they wanted to use in their pieces.

‘‘They have been drawn to different instruments. Sometimes they are drawn to similar ones, but usually through pieces I can sometimes change instruments four times, sometimes six times. It’s good to have variety, There are a variety of voices represented through the collection of compositions.

‘‘The composers have been sensitive in their choices so that the voices do not overpower the flute. They have tended to gravitate towards the textural, melodic taonga puoro.’’

Instruments such as the pupo rino or koauau tutu, known to be used in Murihiku (the southern part of the South Island) for musical instruments, and the shell, hoputea used in Carr’s work.

‘‘The voices of the instrument are unique to the instrument. Each one sounds different depending on the materials, how you make the inside and who plays them — it can sound different in someone else’s hands.’’