Some of the rawest stuff didn’t make the final cut of the King Loser documentary.

Which is saying something. This music doc shines a light just as hard on the ragged scars as it does on the wide sly smiles below.

For example, we do witness the angry mid-tour claustrophobia of a small hotel room in which no-one is talking below shouting. But, what we’re shown of that could have been worse too.

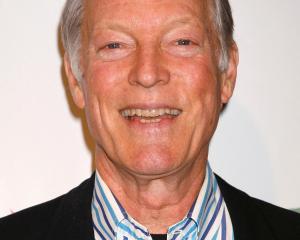

"Like I would be filming for a while and they would be going at each other," co-director Andrew Moore says.

"I would just stop filming them and go for a walk, which I suppose is not what D.A. Pennebaker would do, but I am only human, sort of thing.

"And there was a classic one where in Christchurch I was filming them and they were really tetchy with each other, they were just going at each other and it was just getting too much for me, and I was like ‘I’m going for a walk’. I came back and they said ‘where were you? Celia just attacked Chris with her walking stick, you should have been there’," Moore recalls.

"But if I got 30% of the craziness it was still going to be pretty crazy and I got more than that."

Moore’s film, which features in this month’s Whānau Mārama New Zealand International Film Festival, started out as a fly on the wall diary of the band’s 2016 tour, a couple of decades on from its mid-air ’90s disintegration — but became rather more than that.

King Loser was big in the ’90s, if you we were up late enough. They opened for Dinosaur Junior and Sonic Youth and did the Orientation tour.

But there was always trouble in their pharmaceutically-fuelled paradise.

The band’s original drummer, of which they rattled through a large number, Duane Zarakov (aka Pat Faigan) sums it up on screen: "Well, put it this way, we took drugs".

"We had a bit of an us against the world vibe ... but also us against us, too."

And then there were the big personalities.

Writ largest in Moore’s film is Celia Mancini, bassist, keyboardist, vocalist — a maximalist character of her own creation.

She and guitar wizard Chris Heazlewood were the heart of the band and reprise their lead roles for the film.

Heazlewood spun off Dunedin’s roiling ’80s band scene, carrying with him a scratched vinyl collection of influences from Records Records and elsewhere, to form King Loser with Mancini in Auckland in the early ’90s.

They wrapped filmic B-grade sensibilities and carefully curated op-shop wardrobes around a similarly magpie psych-rock blending of surf and lounge with other noisier influences — think a grittier Pulp Fiction, they had a similar penchant for instrumentals.

There was time to build a formidable live reputation and record three albums before the 1997 dissolution.

In its wake, Heazlewood spent time living under a bridge.

Then, an invitation in 2016 to play the Auckland music festival The Others Way — for which they were billed as a "notorious Flying Nun act" — gifted the opportunity to get the band back together.

Moore previously appeared on the Whānau Mārama New Zealand International Film Festival bill with his film No More Heroes, about Aotearoa’s ’70s skateboarding pioneers, and says that five-year project all but exhausted his interest in film-making.

"I said after the skate doco I was never going to make another film because it was just too bloody hard."

But a smouldering ambition to make a music documentary lingered. The question was, about whom?

Enter King Loser.

"When they said they were getting back together it was, ‘OK, that’s perfect’.

"This is my ideal New Zealand band to make a film about because while they may not have been hugely successful, they were the most interesting characters and the most extreme characters," Moore says.

"They were the last scary, dangerous band I think. It’s all pretty sanitised now but they were like the Sex Pistols or something."

Added to which, Moore had first met Heazlewood and Mancini back in their earliest practice room days together and had become their unofficial camera guy at the time.

And, given they planned a short national tour on the back of their Others Way appearance, the project appeared to be neatly and achievably framed.

"I was, like, just film a tour, it will be over in a few weeks and then we can spend a few months editing it and then the film is done.

"Little did I know, seven years later."

The endeavour morphed into something quite different, Moore says. Bigger and messier by far.

"I came back from the tour and it was like, ‘that was bloody hard work’. I didn’t look at the footage for a while because I was a bit traumatised."

Time passed, he broke his ankle and, laid up, got back into the raw material, then battled away, "just trying to keep pushing forward, you know".

Among the reasons for the film’s inflationary trajectory was a wealth of material. Early on Moore put a call out for archival contributions — photographs, videos ... It duly arrived. Mancini herself was a dedicated archivist, Moore notes, consistent with her world-building approach to life.

At about this point, the clock spinning and the film expanding well beyond a musical travelogue, Moore’s co-director Cusha Dillon became involved.

"Cushla had been keeping an eye on things and helping out," he says.

An experienced and widely respected film editor, she disappeared into her home editing suite with Moore’s early efforts, putting Covid lockdowns to good use. Some time later, Moore was presented with the results.

"She’d changed it quite a bit, but it was looking really good."

From that point, it was a team project.

It was a natural pairing as both had been fans of the band back in the ’90s and indeed had each made music videos for them.

Despite both being fans, there was no suggestion of hagiography or sanitisation, she says. The band insisted there be no filtering.

Heazlewood himself sets up the narrative early in the film: "The whole, sort of, ethos of King Loser is you are encouraged to fail because when you fail, there is the measure of how much gas you have got in the tank."

There would be no slowing down for the corners.

"Throw in too many free drinks, pharmaceutical malaise, technical incompetence and you have got the perfect recipe for something that is either going to take off or plummet like a piece of lead to the sea. Yep, rolling the dice with the King Loser," he continues.

Back in the day, interviewed for TV he put it like this: "We’re poor and stupid and music is our life", qualifying that the statement worked equally well backwards.

Moore and Dillon wrestle the camera into a focus on the tales of love, crime, record dealing, double-dealing, determinedly arrested development, inconsistency and notoriety that piled up around the band without choreography.

"There is some tough material in there," Dillon says.

"It is kind of fun and little bit crazy and a little bit whacky but there are some serious themes through that and it was important to not disregard or take that stuff lightly, but to also make it palatable and I guess my skills as an editor helped that."

Moore says there was stuff they left out, that was simply too much, stuff connected with Mancini’s family, members of which appear in the film.

"It was almost like she was having a mental breakdown or something at some times."

Mancini could be pretty tough on people, he says.

For Mancini, the assessments stand as eulogy, as she died in 2017.

Dillon says one of their aims with the film was to document the breadth of her talent — by no means limited to King Loser’s output — without downplaying her struggles with mental health.

Taking editorial control in those situations, as director, allows an audience to be brought into the world, to a place of understanding, she says.

"Because it is not a world that a lot of people know — but these are real musicians who live and breathe music.

"I really hope there is joy in this documentary. It was really important to give the humour and the absolute joy of King Loser and of their gigs."

It is not the documentary you’d make about Dave Dobbyn or Don McGlashan or Tim Finn, the people for whom rock’n’roll ultimately delivered success as conventionally measured, she says. In fact, most people draw a blank when she talks about King Loser, but that shouldn’t matter in terms of the film’s appeal.

"It’s sort of, like, have a watch and get your world widened."

The music documentary genre can be vacuous, overpopulated by the talking heads of famous people talking about other famous people, she says.

"And, quite frankly, those films are boring and there were famous people, famous New Zealand musicians interviewed for this documentary but most of them haven’t made the cut because it is just not that film. Who cares what David Kilgour thinks or Martin Phillipps thinks. Let’s bring the audience in and experience it and make that decision for themselves."

At its core, King Loser is about the life of a jobbing musician, she says.

"In a way sometimes those little, small stories are the most compelling and the most interesting. It is the detail, it is the authenticity, it is the mundane."

It is Heazlewood struggling under the weight of a heavy keyboard that needs to fit in the back seat of a car with too many miles on the clock already. That is the life right there, Dillon says.

In the final analysis, Moore says, the film is about the relationship between Heazlewood and Mancini, around whose shared aesthetic the band built its music and whose friendship and collaborations survived the King Loser split.

"It is about a band, it is about the main two people never giving up and just keeping on going. They were dedicated, you know, there was no backup plan for those guys. That was all they were going to do with their life, it was just play music. There was no plan B."

Heazlewood, is an amazing musician, who has only got better with time, he says.

"The good thing about the 2016 tour is that a lot of people came to the shows who had never seen them. When they got back together and started playing, the old magic was still there. Everyone had gotten better, had been listening to the songs for years and came in hot. The first time I saw them practising, I thought ‘shit this is better than you were back in the day’ kind of thing."

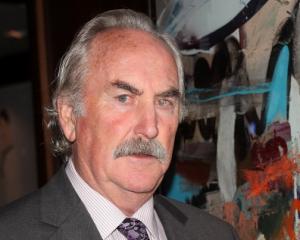

Heazlewood, a defiant, if philosophical, presence in the film, has long been open about struggles with the various demons he summoned, and wears the weathering of the road he chose.

But if he or Mancini ever stopped to wonder whether it was worth it, Moore is confident that they’d have been happy with the ledger.

"I am sure if you had asked both of them, they would have said ‘yeah, it was totally worth it’, you know."

And if it is a question of ledgers, Moore’s content that his film will square things further in their favour.

As far as he is concerned, as a fan then and now, King Loser were never given their due.

"When they were around they were always slightly out of step with what was happening at the time, you know. They forged their own path, created their own thing. I really loved them back then and I was like, ‘we have to show the kids what real rock’n’roll is like’, you know."

For that reason, and others, Moore is pleased he stayed the course with his film.

"It has been long and daunting but I am glad I hung in there because it is going to be an awesome tribute to these guys. I think people are really going to get a kick out of it. I have never seen another New Zealand documentary, music documentary, like this."

The film

- King Loser screens at the Regent Theatre, Saturday August 19 at 8.30pm, as part of Whānau Mārama New Zealand International Film Festival. www.nziff.co.nz

- Cash Guitar, featuring Chris Heazlewood and special guests, will play following the screening.