Today, almost everyone has a pocket-sized version that also takes photos, shoots video, sends e-mail and surfs the Internet. About the only thing it doesn't do is protect your feet.

Get Smart comes to the big screen next week, along with a spate of new spy gadgets to help Maxwell Smart, Agent 99 and the other spies at CONTROL. The gadgets are just as goofy as they were in the original TV series, but because technology has caught up with the writers' imaginations, there's a big difference: many of the movie's doodads actually exist.

"Our favorite thing is to take something that does sort of exist and just exaggerate it a little bit," said Matt Ember, who co-wrote the script.

The film shows a tiny iPod alongside spy-worthy stuff such as a two-way tooth radio and a digital "spy fly" - all of which are available now.

"It's pushed to a level of success that perhaps it hasn't achieved in the real world, but it's real, it's out there, so that's fun" added co-writer Tom J. Astle, a self-described science nut.

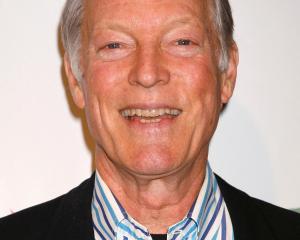

Director Peter Segal said he originally couldn't believe such devices were real.

"I said, 'That's too silly. I don't think people will buy it,'" he recalled telling the writers. "Then they Googled it and it came up as an actual thing."

Astle and Ember saw the tooth radio in a magazine and thought it was a perfect fit for the film.

"That's an example of taking inspiration from the old series in spirit," Astle said. "The inherent comedy of having a microphone in your mouth - it's really close to your voice and it's easy to yell and be too loud."

The inextricable link between gadgets and spy movies began with James Bond in 1962, said TV historian Tim Brooks, author of The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows. The often-preposterous devices Bond used added levity to a genre that "had always been deadly serious" during the early years of the Cold War, Brooks said.

Back in the day, Get Smart ratcheted up the goofiness level with bulletproof pyjamas, a Bunsen-burner phone and other wacky gadgets that often didn't work. When the show debuted in 1965, the nation was future-focused and obsessed with the promise of technology.

The show played on that obsession, Brooks said, introducing dozens of covert gadgets and props designed to make life easier for Cold War-era secret agents.

A cigarette lighter doubled as a .22-calibre gun. A lipstick could record conversations or release poisonous gas. Then there was the famous shoe phone and the always-dysfunctional "cone of silence" that could (theoretically) keep conversations private, even in a crowded room.

"It's nothing that you would expect to find or would even make sense in real life, and that's the gag," Brooks said. "It was part of what the show was about. You'd watch wondering what's next, where's the phone going to be next time. ... It was like a satire of our fixation with gadgets."

The movie also takes liberties with some familiar devices, such as portable lasers, retinal scanners and a tricked-out Swiss Army Knife equipped with a flame-thrower and a mini crossbow.

Despite living in a high-tech world, movie fans still love spy gadgets, the filmmakers said: Just look at the success of the Bond franchise, which will soon introduce its 22nd installment, and spy spoofs such as Austin Powers.

Part of it is the undercover element, part of it is a cultural love for technology, and part of it is wishful thinking.

"Human beings are tool-users," Astle said. "We would like to believe that our government - the good guys - have within their power tools and electronic gadgets that will protect us that are beyond what we could do."

"There is some reality to it," Ember said. "We do have facial-recognition software, but on the other hand, I'm not allowed to bring shampoo on an airplane."