In a single paragraph in Liam McIlvanney’s new crime thriller The Heretic, the reader is confronted with "crabbit", "shinty" and "neds".

Elsewhere, there’s "clype" and "teuchter" and "sgudal".

So we’re back in Scotland, Glasgow, familiar territory for the University of Otago Stuart Professor of Scottish Studies, who with The Heretic delivers a sequel to The Quaker, his Scottish Crime Book of the Year from 2018.

Protagonist from that book, detective Duncan McCormack, is back on the mean streets of Scotland’s toughest town, it’s 1975 and terrible deeds are being committed by bad people. Victims are innocent or less so. The "polis" are at least as hard as they need to be.

All that Scots vernacular is not just for show, to lend authenticity’s sake, McIlvanney says.

It’s his language, the one he was born to in Kilmarnock and grew up with.

"These are just my words, to me."

In person, McIlvanney translates much else into a more lyrical tongue. The word "crime", for example, in his telling, seems to emphasis the first three letters, the "cry". Complete with burr, it fills with extra meaning.

Perhaps that was why casting Gordon Jackson as the gaffer in The Professionals worked so well, or why when Mark McManus’ Jim Taggart declared a death to be murder, it was a darker turn of events. There’s veracity in a Scottish accent.

But McIlvanney also says he’s careful not to overdeliver on the Scots.

"It’s a trade-off, isn’t it. You want to try to create an authentic sense of place and in the case of Glasgow I think that really involves the kind of language that people use. At the same time you don’t want to make that element so foreign or dense that readers from elsewhere are all at sea.

"My French translator for The Quaker had footnotes where he would explain some of the cultural references and so on," he says, admitting the idea of a glossary has occurred to him.

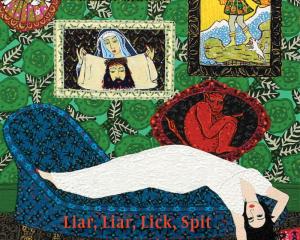

But for fans of his novels — this is his fourth crime story, all previous met with critical approval — the familiar is among the prime reasons for bending back the ambiguous cover art.

Hero of The Quaker, Duncan McCormack, has returned north of the border and is soon beset from all sides.

McIlvanney hadn’t expected to be following McCormack around again, having conceived The Quaker as a standalone. But then his editor suggested a curtain call and now the writer is thinking about further possibilities for him.

There are things to consider when casting a character a second time, he says, particularly when it wasn’t planned and you are stuck with where you left him last time.

"I have come to realise that writing a sequel is not as easy as I thought it would be. You have this idea that you have set up a lot of the machinery in the first book and that you can just pick up where you left off. You are writing the sequel. But it doesn’t really work out like that in practice.

"Even just in practical terms you have to remember what you have committed yourself to in the first book."

Still, it was nice to return to the same character and feel his way back into McCormack’s consciousness and personality.

Not that a biographer’s grasp of the character’s every trait and foible, is required.

"I am a greater believer in a thing the American playwright David Mamet says, that character is action, basically. That you don’t need to worry too much about understanding everything about a character’s backstory, you just give them a dilemma and see which way they jump and that tells you about the character."

Backpedalling just a little, McIlvanney says a deeper understanding of the character does let you know which way they’re likely to jump.

There’s plenty of jumping to be done in the novel’s 500 pages.

It opens with a prologue that sets a grim tone.

"I tend to be quite big on prologues," he says. "The hope with a prologue is that you plunge the reader into a dramatic piece of action, then partly what you are doing in the rest of the book is explaining what and why this happened."

McIlvanney says when writing, his approach is to have the major plot points mapped out, a series of acts all of which lead to their own climax or false victory.

"Then I tend to wing it, in between those points. I sometimes think of it as a series of rafts in a stretch of water and you dive in from one raft and you flounder until to get to the next one and pull yourself aboard."

It’s all in the service of delivering a sufficiently satisfying conclusion, dealing some justice.

"You have art partly to supplement the shortcomings of life. So, partly the point of a crime novel is to supply the kind of closure and happy resolution of a terrible event that you don’t always get in real life.

"You want a novel to do something that life doesn’t. You want a novel to be realistic but, as I say, certainly in the case of a crime novel, I don’t really see the point in leaving things wildly open ended at the end of a novel, because that’s kind of the point of the genre really."

It sounds a lot like a writer on top of his game. But he’s having none of that Sassenach self-congratulation.

"You are talking to someone from the west of Scotland. Enjoying things is not really on our cultural radar," he says with a chuckle.

"You are always starting from scratch in a way, with a novel. You always begin a novel by thinking ‘I can’t do this, why did I ever agree to write this book, I am never going to get to the end of it, I am going to be unveiled as a charlatan’. I think that is just the default position of writers, basically. I don’t know if you ever reach that stage where you think, ‘yeah, I’ve got this, I know exactly what I’m doing’. And I think the stuff you wrote in that frame of mind wouldn’t be as good as you write when you think ‘what the hell am I doing’."

As an aside, he says his wife, "who is always able to bring you down to earth in these situations", read a cover endorsement on the new book, "An absolute master", as "an obsolete roaster".

"Possibly closer to the mark," McIlvanney considers.

Insults and modest demurring aside, McIlvanney admits to being 50,000 words into his next novel already, which offers the prospect of books in consecutive years. It’s what most crime writers regard as minimum required output, he says, but something he has never achieved himself.

Then there’s the 10,000 words of a police procedural set in Dunedin, something he’s been tinkering away at between other projects. But that’s regarded as a longer term prospect.

For now, he remains more comfortable in the old country, where the cultural references are second nature. It’s Fairlie next, on Scotland’s Ayrshire coast, a small-town psychological thriller.

And anyway, with a day job at the university and a home life involving four children, getting through a couple of hours crime writing a day seems better than reasonable productivity.

"You can’t actually do more than two or three hours in a day," he says. "I admire these people who can sit down and write fiction for eight hours a day, but I am certainly not one of them."