House of Names, by Colm Toibin, and Bright Air Black, by David Vann offer reworkings of Greek myths. Tragedy, indeed . . .

Two recent novels by male authors offer retellings of two Greek myths centred on powerful, vengeful women.

Both involve similar themes of betrayal and vengeance, guilt and regret. They feature savagery, sacrifice and murder most foul. Gods are invoked, kings are doomed, and families are fair game. The resulting books are brutal bloodbaths.

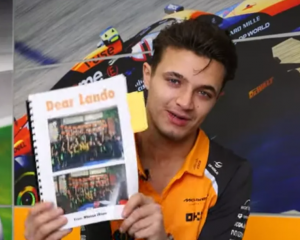

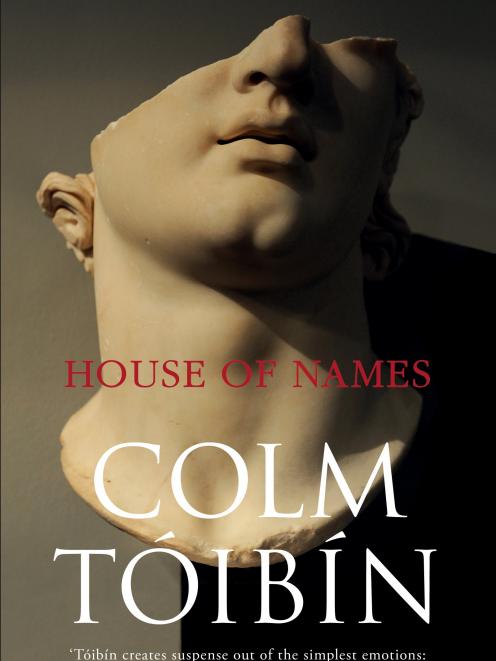

HOUSE OF NAMES

Colm Toibin

Picador/Macmillan

Irish writer Colm Toibin has chosen the story of Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae.

His narrative is shaped by Aeschylus’ The Oresteia, Sophocles’ Electra and three Euripides’ plays Electra, Orestes and Iphigenia at Aulis.

Set at the time of the Trojan campaign, the book goes back and forward in time and is told by several protagonists: Clytemnestra, her son Orestes, and daughter Electra. This is a good device whereby the reader gets to know each character, understands their thoughts and perspectives and feels their pain and loss, which helps us reflect on their actions.

Although the war is (eventually) won, there are no winners in this royal family. Rather, the sins of the father are visited in appalling fashion on his flesh and blood as one by one they seek to avenge each other’s deaths.

Clytemnestra begins the novel with the words ‘‘I have been acquainted with the smell of death ...’’ which sets the tone for the rest of the novel. She goes on to (graphically) recount the ‘‘sacrifice’’ to the gods of her beloved eldest daughter, Iphigenia, by Agamemnon, so the Greek forces will be granted favourable winds to make the passage to Troy (after Helen’s abduction by Paris).

Unable to persuade Agamemnon against the killing, and feeling similarly abandoned by the gods, Clytemnestra takes a lover and plots her revenge on Agamemnon upon his return a decade later.

Orestes - a young boy at the time of his sister’s murder - has been sent away, ostensibly to be protected, but ends up being locked up with a group of kidnapped boys, whose families are deemed a threat to Clytemnestra’s rule. Orestes and two others eventually escape and eke out an existence, living with an old woman. His part of the tale is engaging and makes for some lighter relief. Compared to the goings-on in the palace, life is somewhat idyllic, he falls in love, is content, but is eventually pulled back to confront the reality of his parents’ crimes.

Meanwhile, his other sister, Electra, has been biding her time, coldly watching her mother and her lover, waiting for her brother’s return and for her time to exact revenge.

Despite the graphic content of the story, the more conventional structure and style of Toibin’s tale makes for "easier" reading than Alaskan-born/US writer David Vann’s novel.

David Vann

Text Publishing

Vann - who lives part of the year in New Zealand - is one of my favourite authors. He leans firmly towards the dark side, and water is a common preoccupation for this keen sailor, whose own high seas experiences inform part of this tale (and other works).

His chosen subject, the priestess and sorcerer Medea ("descended from the sun and worshipping darkness") is a good fit, therefore. The story is told in the third person, but from Medea’s perspective. It begins with she and Jason fleeing aboard the Argo from Colchis across the Black Sea to Iolcus. They are in possession of the Golden Fleece and her father, King Aeetes, is in hot pursuit.

As in Toibin’s novel, from the start readers are under no illusions about the bloody content and of Medea’s monstrous actions: ‘‘Her brother dismembered at her feet’’ she tosses his body parts from the Argo into the water knowing her father will stoop to retrieve them. ‘‘Kneeling in her brother, wet against her thighs. Smell of blood and viscera, sacrifice. A smell she’s known all her life.’’Vann’s is an primitive retelling that makes Toibin’s novel seem tame by comparison. Sex and death mingle disturbingly, humans are animalistic in their actions and desires.

We learn that Medea was ‘‘born to destroy kings ... born to horrify and ... born to endure’’. We also learn that her love for Jason (‘‘young and muscled and false, not to be trusted, but he is beautiful and he is all she has’’), and what it has led her to do to her family, is almost instantly a source of regret.

Medea is condescending of the Argonauts, even as they are painted as physically beautiful gods of men. When they finally arrive at the disappointingly small and primitive Iolcus, she realises ‘‘she has given up everything to live with scavengers’’. Despite the fact they have the Golden Fleece, Jason’s uncle King Pelias will not relinquish his crown as promised and the two are cast into slavery - as are their sons, born in ensuing years.

Jason’s weakness is a constant source of misery to Medea. Even when she is able to trick the king’s daughters into killing their own father, Jason will not claim the throne. Forced once again to flee, they head to Korinth, where Jason is welcomed but Medea is enslaved as a sorceress. Jason’s next betrayal will propel her to exact the ultimate revenge.

Vann makes reading a gladiator sport: both compelling and exhausting. His is a monstrous achievement. Rage boils on every page with all the intensity of Medea’s cauldron. He writes in short jagged prose, which echoes the brutality of the content, the harshness and shortness of life, yet his poetic language is simultaneously incandescent.

While hell hath no fury as a woman scorned, the reader - of both novels - is left to contemplate the nature of such violence, of love and loyalty, to what extent we choose our destinies, or whether we are merely victims of fate, at the mercy of the gods, who toy with us and in doing so ‘‘paint the bright air black’’.

- Helen Speirs is former ODT books editor.