Artist, feminist, environmentalist and activist — Marilynn Webb wrapped up all her passions in her art.

Her works are a record of a New Zealand that is no longer, of environments that have been irrevocably changed.

"She encapsulates so many really important concerns — from the 1950s until she died," art historian Dr Bridie Lonie says.

But even though her print-making work is internationally renowned, Webb (Ngāpuhi, Te Roroa and Ngāti Kahu) is less recognised in New Zealand for her contribution to the country’s art and culture — something Dunedin Public Art Gallery curators Lucy Hammonds and Lauren Gutsell and artist Bridget Reweti hope will change with a major retrospective exhibition and book Folded in the Hills.

"All of us felt it was long overdue to make an exhibition that celebrated the scope of Marilynn’s career in art and celebrate that. To redress the oversight in historical records to this point," Hammonds says.

The curators say even though Webb’s work is well known in the Dunedin artistic community, the exhibition is a way of raising awareness of Webb’s practice at a national level.

"To highlight and honour the value she has in New Zealand art and make a stand or point of it," Reweti says.

Lonie, who wrote a book with Webb in 2003, agrees, describing Webb as something of a "prophet" for want of a better word.

"She argued fiercely for what she believed in. She wanted her work to be useful and valuable, to speak of everyday concerns and values."

However, some acknowledgement of her work came in her later years. She was awarded an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for her services to Art and Education in 2000 and in 2010 Webb received a University of Otago Doctor of Laws Honoris Causa for her contribution to Art and Art Education, followed in 2011 by a Ngā Tohu a Tā Kīngi Ihaka from Te Waka Toi in recognition of a lifetime contribution to nga toi Māori.

It looks at her early works in the 1960s —when she was based in Auckland and travelling around Northland as a specialist arts adviser in schools, while also developing her own practice — to the early 2000s, when she was deeply immersed in the history of place, and water began to feature more strongly in her work.

"There is a real continuity of thinking and relationship of what it means to be an artist — what it means to be an artist in Aotearoa and have a relationship to that place in which you are working through your practice," Hammonds says.

"It is totally consistent, despite it taking radically different forms and expressions throughout the exhibition."

Reweti says it is important to be able to position Webb, who was born in Auckland and raised in Ōpōtiki, Bay of Plenty, alongside her contemporaries of her era.

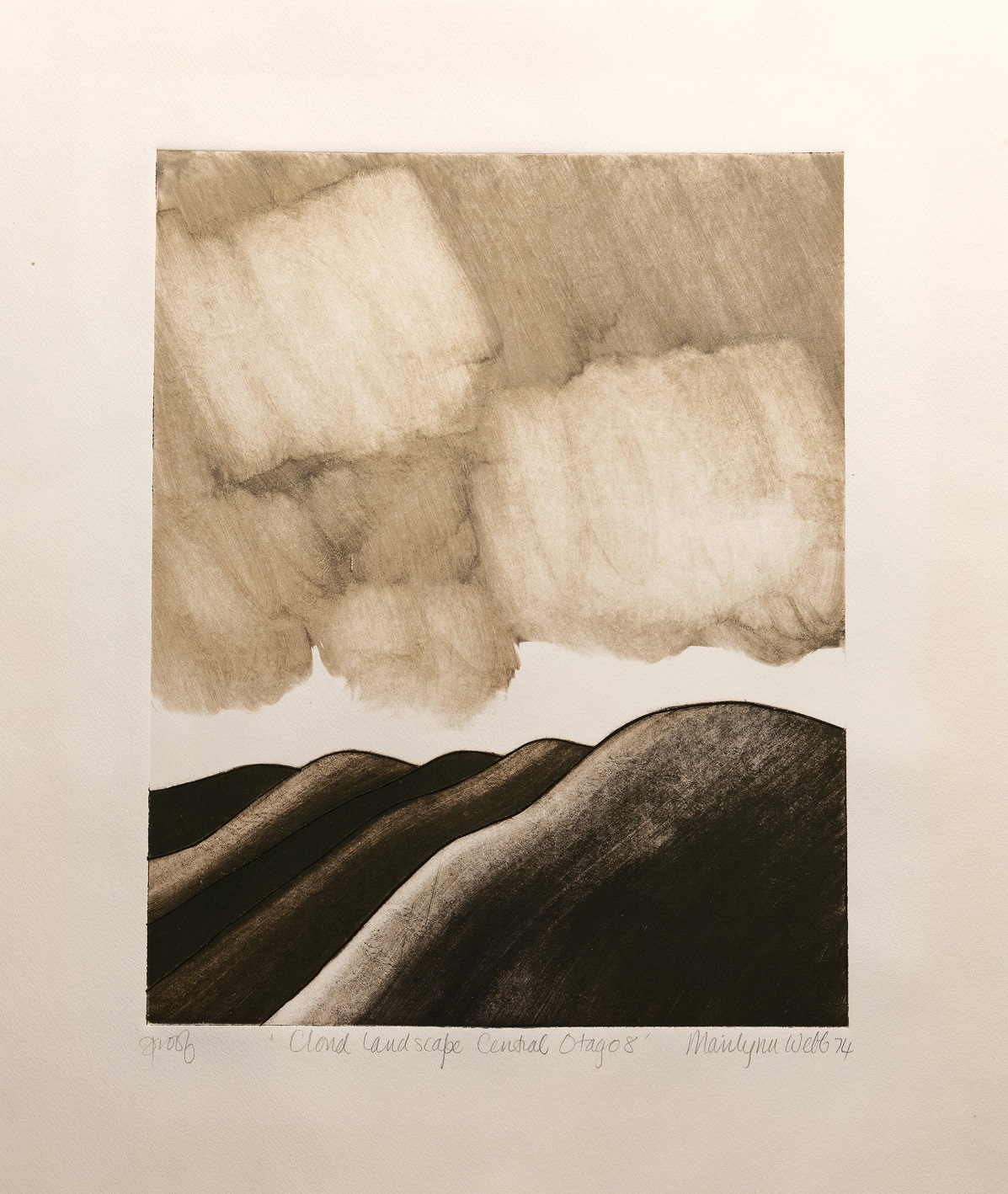

The exhibition marks important milestones in her career such as being awarded the Frances Hodgkins’ Fellowship in 1974 — the first Māori woman and first and only print maker to do so.

"She made the decision from then on she was going to pursue life as an artist, fully committed, largely driven from a studio practice from that point on," Hammonds says.

Gutsell says it brought Webb back to Dunedin where she trained at teachers college as part of the Gordon Tovey’s art and craft scheme in the 1950s and she began to develop a deep relationship with the South that continued throughout her life.

"You see her coming to know [the area] and gradually developing this commitment to basing her life here."

Her first exhibition was in 1957 at Stewart’s Coffee House in Dunedin. It was of paintings, as she did not delve deeply into print making until the 1960s, when through her work in education, she had access to printing presses.

"In the ’60s everybody didn’t have a printing press in their studio. The equipment was hard to come by, so she had that opportunity. I suppose she found space to be experimental, to find a way of making imagery that she found creatively stimulating."

"It is interesting from an art historical point of view — how many things collided in the ’60s and ’70s that cemented that commitment to print making."

Part of that was the huge international interest in print making in the ’70s. A lot of different initiatives were established which raised the profile of print making and gave more opportunities to artists and print makers.

"Over her career she found a community and an audience who supported her practice over decades."

Another was what Webb called her "accidental" discovery of what became known as the Lino Intaglio process. She carved a plate too deep and then over-inked it, so when it went through the press, the paper was pushed deep into the cuts on the block and the paper became raised.

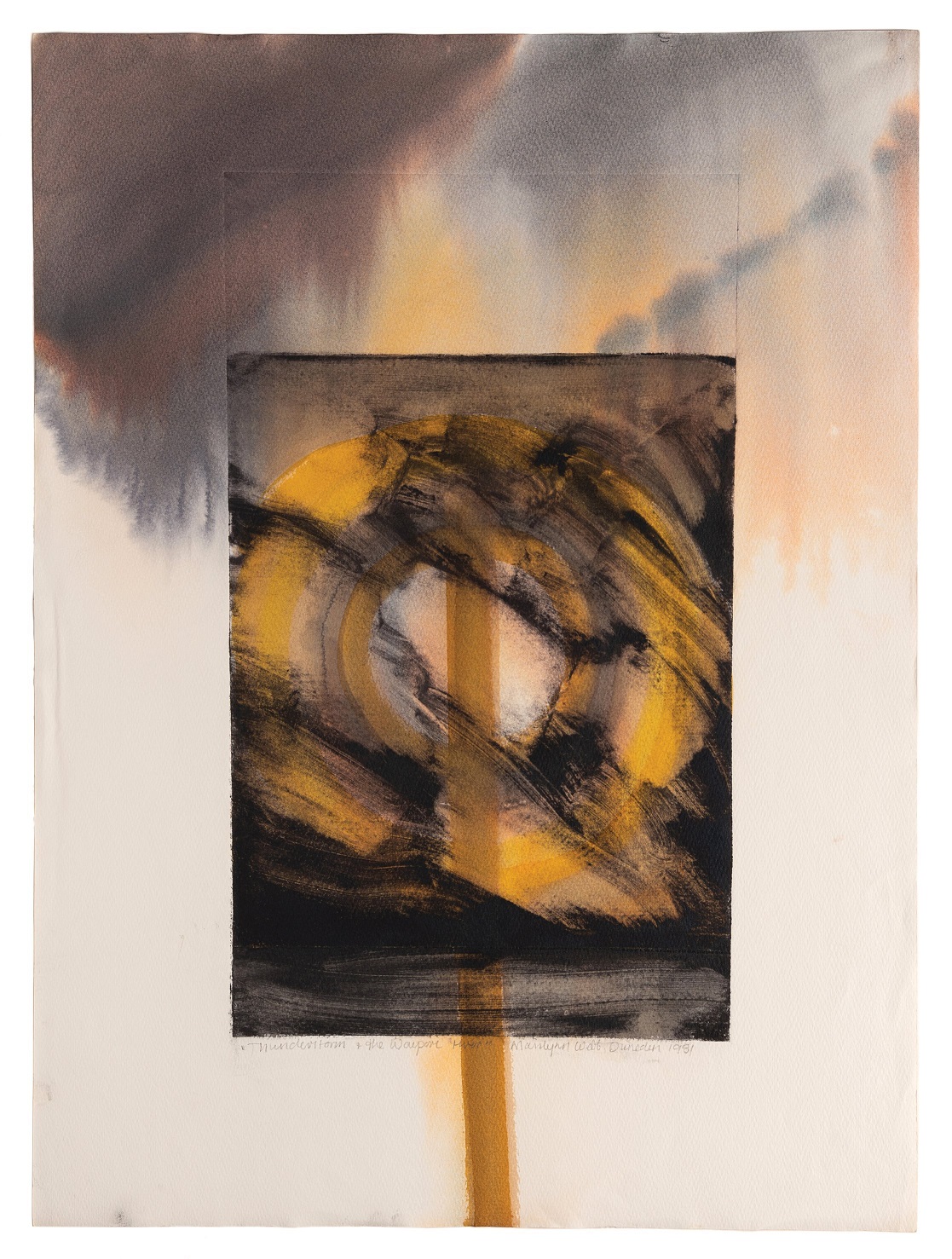

"For Marilynn that was a light bulb moment — an opportunity in how she could come to an art form, which developed into a Lino Intaglio printing process. Over time she blended the technique with mono printing, etching and hand colouring."

Webb, who continued teaching for much of her career producing some of New Zealand’s top print makers, also challenged the perceptions of print making. At the time it was considered a craft practice or minor art form as works were reproducible.

Lonie says Webb argued against that to the New Zealand Print Council and ultimately shifted her practice to make it unique by combining printing with hand painting.

Hammonds says understanding the innovation in Webb’s work was important as it played a major part in her commitment to the form.

Webb was widely travelled and exhibited throughout the world.

"She had a deep commitment to her practice as a printmaker, and disrupting it at the same time, which is what was recognised in those communities throughout the world. There was something unique in character about her practice."

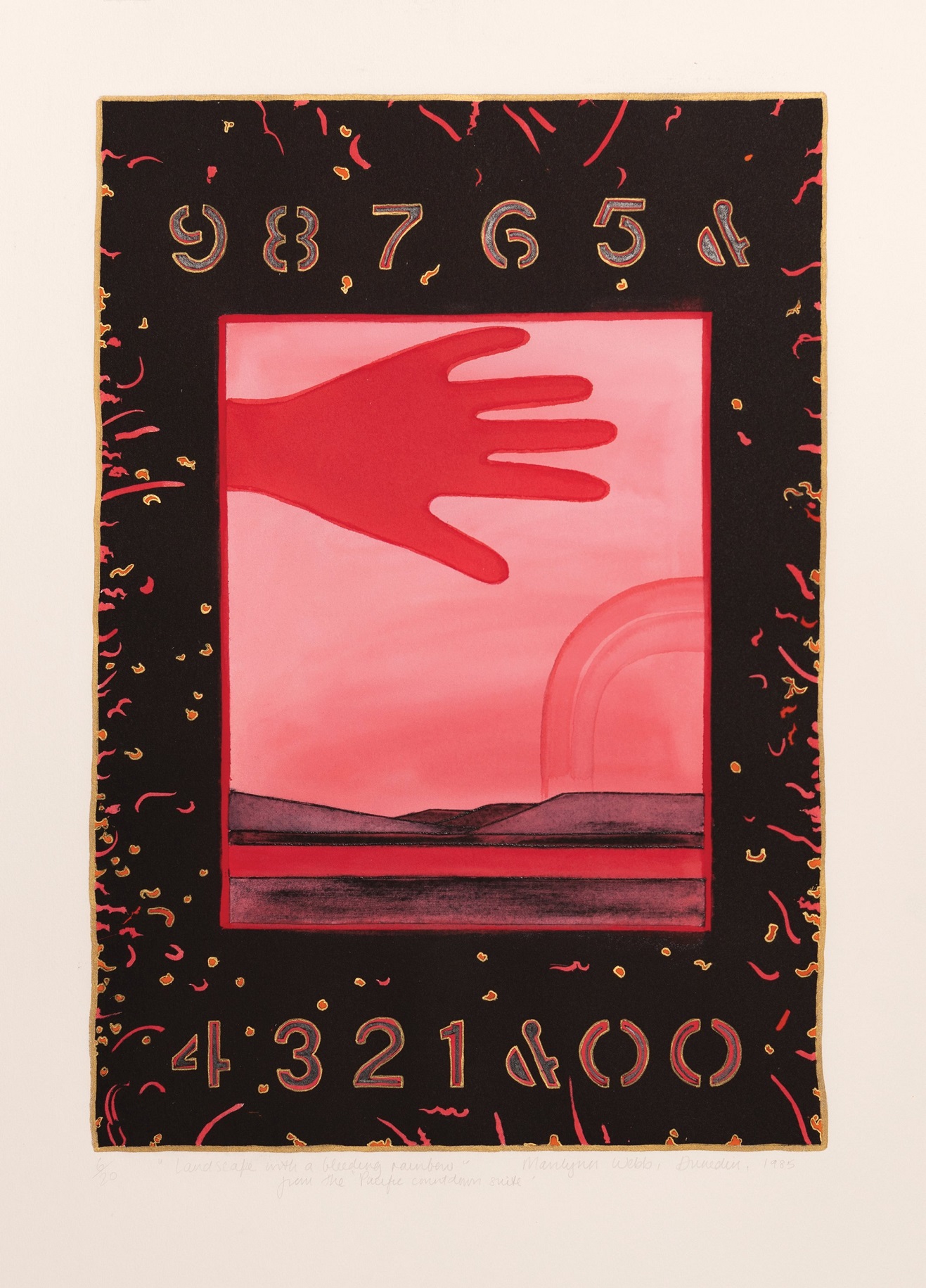

"The coalescing of different issues in the community, and that were high profile in Aotearoa — specifically infrastructure of the Think Big era and, for Otago, the aluminium smelter at Aramoana — was a pressure point for many in the community. Also hydro electric schemes, things that impacted or made incursions on to the environment. Nuclear testing in the South Pacific was another."

Lonie says Webb, whom she describes as "funny, feisty and clever", was often at the "margins shouting" taking often "unfashionable positions" at the time.

Hammonds says the exhibition looks in particular at what it means to stand in defence of something throughout an artistic practice.

"She often talked about how important it was to make her voice heard."

In parallel to those works are her "protection works" which move in and out of those issues often with references to her Celtic history.

"There is a holistic gesture of protection of specific places or points in time that she felt were important to her. Her commitment to activism, the environment, politics or feminism was deeply important to her as a person."

The exhibition also has a break-out focused on Lake Mahinerangi, a place Webb returned to repeatedly over her lifetime and included in her work, allowing a look at the place and how important it was to her.

Gutsell says the exhibition also focuses on the later phases of Webb’s work, in particular her journey of exploration across the landscapes of the lower South Island such as the Mataura River and Fiordland where she spent a lot of time in later years.

"They’re very beautiful and profound works."

Lonie says Webb’s work mapping the environment in Eastern Southland and similar work in Dusky Sound and Stewart Island all consistently involved the local community.

"She built community."

"There is a lot of symbolism, emotion and energy — you can track the use of red, pinks and greens."

Again, looking at the works from early in her career to later in her career, they are very connected, but also could not be further apart in terms of visual language.

Hammonds says Webb’s consistency of vision tracked so much of Aotearoa’s social, political and culture development from the 1960s until she died.

"Making the exhibition ... gives sense to the things she railed about.

"She talked openly about barriers and frustrations and it became quite apparent when you look at the scope of work — from the inability to recognise print making for full worth to difficulties pursuing an artistic career as a woman and mother."

The exhibition provides an "amazing opportunity to show all of these important things her work carries".

She says recording women’s art history is crucial.

"It is still lacking in Aotearoa, there are still huge gaps and Marilynn is one of those."

Her work leaves a legacy of "hugely salient points" for the current moment, she says.

To see

"Marilynn Webb: Folded in the Hills", Dunedin Public Art Gallery, December 9-April 7.

Exhibition tour: Curators Lauren Gutsell, Lucy Hammonds and Bridget Reweti with special guests Jim Geddes, Bridie Lonie and Cilla McQueen, Saturday 11am-noon.

Lino Intaglio engraving workshop: Introduction to linoleum engraving by print maker Faith McManus, Saturday 11am-1pm.