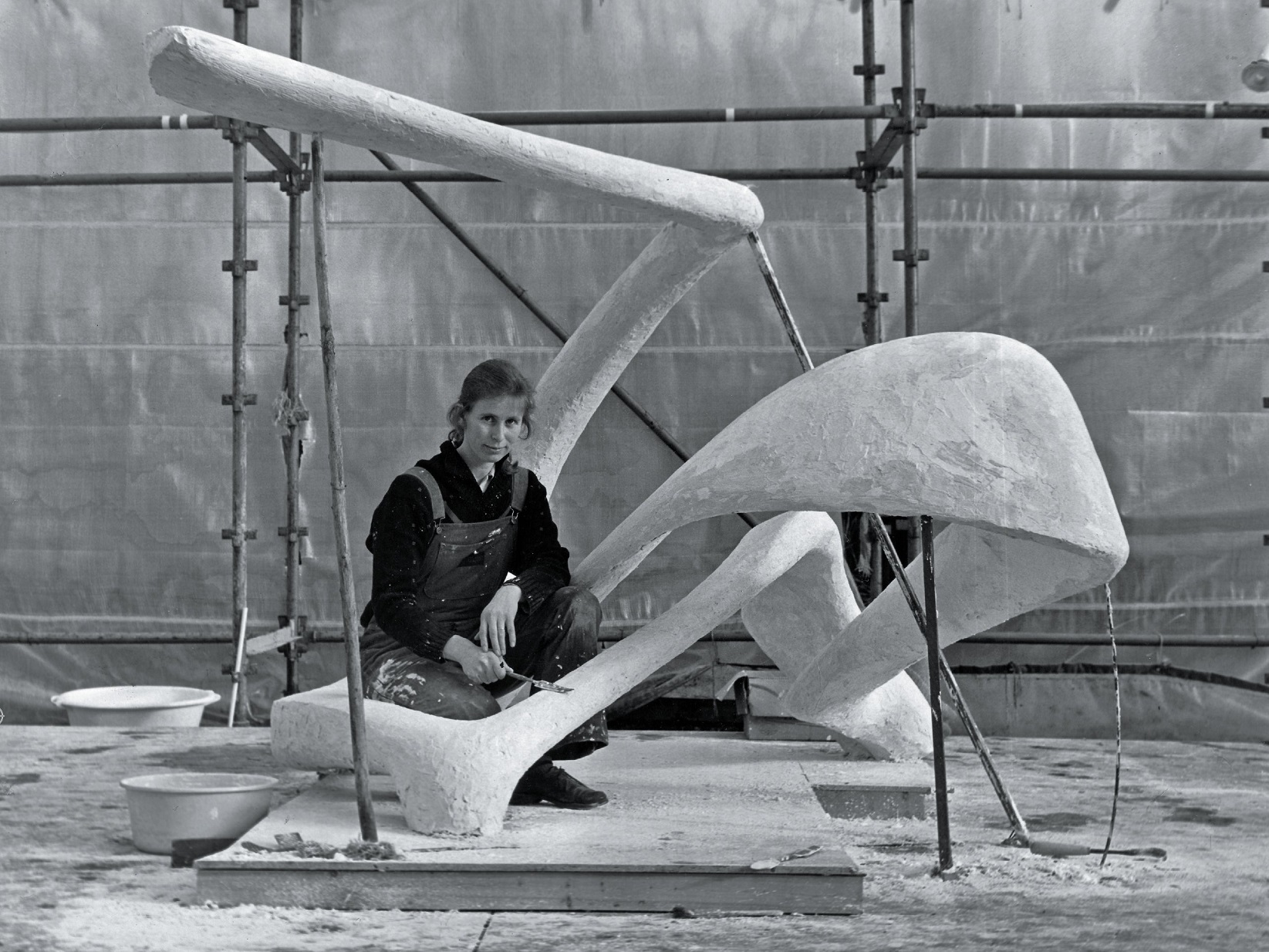

A large block of Carrara marble Tanya Ashken bought in Dunedin in 1967 is only now taking its final shape.

Called Gaia, when finished, the sculpture is the last to be made from three blocks of marble Ashken bought from a stone mason when living in Dunedin as the Frances Hodgkins Fellow in 1967.

Ashken, who was English, had come to New Zealand three years prior with her New Zealand husband and artist, the late John Drawbridge, and settled in Wellington.

"It was very different from my life in England and very dull."

Luckily she found Dunedin to be a lot more exciting, partly because of the people who lived there. As Drawbridge had spent this third year of teacher training in Dunedin, he had many friends who still lived in the city.

"They became my ready-made friends, especially Rodney Kennedy and Charles Brasch. James K. Baxter was into his second year as Burns Fellow and a good friend of John’s and introduced me to Patrick and Roselle Carey and the Globe Theatre. That led on to many other great connections. "

She also found a connection with Philip Smithells, the professor of physical education at the University of Otago at the time. He had attended the same school in the United Kingdom as she had, only 30 years earlier.

"We became instant friends."

"Mr Buchanan, the head of the School of Mines, rushed up the stairs and said ‘it was like a herd of heffalumps dancing up there’."

She ended up in the semi-basement area of the building which went on to house the department of geology.

There she started "building up a large shape" using wire and plaster which she eventually called Seabird II. Then she got her three blocks of marble from a local stone mason and worked on one of them for the rest of her fellowship year.

It became Aphrodite (1967), which is now in the collection of the Auckland Art Gallery. The second marble sculpture, Apollo (1973), was completed after her first son was born and bought by Aratoi art gallery and museum in Masterton.

Her time in Dunedin proved to be very influential on her work and reinforced her love of birds. Always a keen birdwatcher, when she and Drawbridge settled in Island Bay in Wellington opposite the beach, it took her fascination to another level.

"The big seagulls outside my studio window were a revelation and I saw the way they fitted their wings into the back of their bodies. This was the inspiration for my first seabird sculpture and even more so when I saw albatrosses off the coast from Portobello during my year in Dunedin."

Ashken’s most recognisable work is the landmark Albatross (1985-86), a 3.5m-high water sculpture overlooking the lagoon on Wellington’s waterfront. It became the catalyst for the birth of the Wellington Sculpture Trust and Hone Tuwhare wrote a poem to mark the occasion.

"It is always a thrill to see Albatross on the waterfront, especially when the water is flowing. Somehow I’ve always known about albatross, even when I was very young. Maybe I was one in my last life."

It was her early life though that set her on a creative path, though one quite different from where she has ended up.

Ashken was born hearing impaired after her mother contracted rubella while pregnant.

At the age of 7, Ashken was sent to a progressive school, Bedales, in Hampshire, where alongside academic subjects she had the opportunity to learn art and craft skills, including metalwork.

"Because Bedales is a co-educational boarding school, there are opportunities for any subjects for every pupil."

At 13, she became the youngest person to acquire her own hallmark after she used silver, rather than the usual copper or gilding metal used in metalwork, to make a present for her parents’ silver wedding anniversary in 1953.

She admits not being able to hear affected her life "completely", but says she was fortunate in her education at Bedales and her family and friends.

"It’s difficult to imagine normal hearing as I am not aware of a lot of what goes on around me. I think my sense of touch is the sense that has developed most.

"My sculptures have many sides to them, [they] ask to be touched and explored by hand and eye."

After finishing school, Ashken went to the Central School of Arts and Crafts (as it was then), where she did a three-year course that included life drawing, design and silversmithing techniques. It was there she met Drawbridge.

"It was love at first sight!" she says.

"I hardly knew anything about art before I met him, as I went to the art school to continue with silversmithing. My life changed completely then."

The couple travelled around Europe, going to many art galleries and visiting churches. Creating church silver was a central part of silversmithing and Ashken went on to create a number of pieces for churches in England and New Zealand.

After their marriage in 1960, the couple lived in Paris for a year. She decided to switch to sculpting and found a studio-workshop with a tutor who specialised in stone carving. She studied at Atelier de Del Debbio, Impasse Rosin in Paris.

"The great sculptor, Constantin Brancusi, had died three years before but his work was still in his atelier. I could see it by climbing up on a mound of marble blocks and peering down from a skylight on to all his works still in there. Brancusi is my only inspiration, with a little from Jean Arp also."

She prefers to work in hard materials such as marble and wood.

"This carries on from working in silversmithing where silver is beaten into shape with a hammer over a metal stake. These sculptures become what they are, solely from my subconscious."

Sometimes, as she did on her first sculpture in Dunedin, she builds on her ideas using wire and other materials before adding plaster of Paris.

These sculptures are cast in bronze and aluminium and become editions.

"My wood and marble sculptures become editions too and cast also in bronze or aluminium."

She has continued to create jewellery and silver pieces for churches over the years, including a silver and greenstone bishop’s crosier for Nelson Cathedral and a New Zealand Arts Council gift of a silver and amethyst pendant, which was presented to Princess Anne in 1970.

Five pendants showcasing her work as a jewellery maker and silversmith are on display at Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Toi Art alongside her Kotuku, a carved kauri sculpture she made shortly after arriving in New Zealand. A scale model of Albatross is also on display.

She is also finishing Gaia and has other small projects on the go. "I’ll never stop working on something."

Ashken says looking back over the 60 years she has been making sculpture, from the first sale of a black marble sculpture from the Redfern Gallery in London in 1963, the response to her work has been uneven.

"I came here at a time when New Zealand was trying to establish a particular style of art that was anti outside influence."

Yet Ashken’s background was heavily influenced by having lived in France and her time in Europe.

"That didn’t go down well here with the art critics. There have always been a few people who have understood what I’m about and have bought my work. But it was not mainstream and in favour."

However, Ashken believes things are changing.

"It is only in the last two or three years that people have become aware of the subtle meaning of my work."

TO SEE:

Tanya Ashken, Fe29, December 2 to January 15.