"I urge you. Find a pathway that will ensure the survival of our kind."

The final words of the mōteatea, an apakura (lament), sung by Paulette Tamati-Elliffe (Kāi Te Pahi, Kāi Te Ruahikihiki (Ōtākou), Kāti Hāwea, Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Mutunga) are a plea from a group of artists who have woven the environmental plight of New Zealand’s freshwater tuna (eels) in the Wakatipu into a contemporary art work.

"We wanted to shine a bit of light, to try this narrative from the perspective of tuna and be a voice for our environment."

The work for Te Atamira, in Queenstown, is a collaboration led by digital and electronic media artist Rachael Rakena (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha, Ngā Puhi), and arose out of a similar film work she and a group of Ngai Tāhu artists created for Dunedin Public Art Gallery’s "Paemanu: Tauraka Toi" exhibition in 2021, Ko te wai, he wai ora, lamenting the degradation and pollution of traditional waterways and wetlands, focusing on the Taieri River.

Rakena wanted that work to have relevance to the younger generation, so asked children what concerned them, and the state of the region’s water was high on their list.

Instead of taking that work to Queenstown when invited to, Rakena proposed creating a work specific to the environmental concerns facing the district.

"So I went back to the team from the Dunedin project and we reconvened to the Atamira project."

As Rakena’s work over the decades has centred around her fascination with water and Tamati-Elliffe’s whanau has been involved in a tuna monitoring project in the district, they are aware of the challenges faced by tuna, the life-cycles of which have been disrupted by hydro stations, so they decided this was an opportunity to highlight the dilemma.

The collaboration saw each artist or creative use their specialist skills to make the story come to life under the artistic direction of Rakena.

She believes 50% of any good installation is in the sound, as it carries the language, knowledge systems, narrative and emotion of a piece.

"All those things are carried through the sound and everything else follows."

So Komene Cassidy (Ngā Puhi, Ngāi Takoto) wrote a lament, with input from Tamati-Elliffe, from the perspective of the female tuna, who understands her inability to take that final journey out to sea to spawn.

"She understands that this time it is not possible so she is lamenting, potentially, that these could be her final days, and she’ll never have the ability to continue her life cycle and have offspring return to that river."

However, while it was originally going to be a lament of extinction, they wanted to express a glimmer of hope.

"So there is a plea from that tuna asking us to find a solution."

Cassidy also wanted not only to encapsulate the perspective of the old female eel as she is dying on the banks of the river lamenting the disruption to her lifestyle, but also that of all the tuna in the lakes whose life cycles are disrupted. So emphasis is given to each stage of tuna’s life cycle to tell that story.

Tūmai Cassidy (Kāi Te Pahi, Kāi Te Ruahikihiki [Ōtākou], Kāti Hāwea, Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Mutunga, Ngā Puhi, Ngāi Takoto), an environmentalist whose first language is te reo Māori, was brought in to translate H.K. Taiaroa’s words recording the mahinga kai (food gathering), place names, activities and landscape of Canterbury and Otago in Māori. His interpretation as a first language speaker is different from those who speak te reo as a second language.

"Tumai’s research has given us a very clear idea of what things might have looked like at that time, particularly the types of birds [and] trees, information which helped inform a lot of the work we are doing in the art space and environmental space and our work to try to revitalise not only our language but our environment — we feel very strongly the work goes hand in hand."

Tamati-Elliffe says the environment of today would be unrecognisable to their ancestors, so it is important to try to protect remanent areas that are left and ensure once abundant populations are protected and preserved so they can be harvested into the future.

Entwining with the lament is the music of Laughton Kora (Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Pūkeko, Ngāti Awa), a former Queenstown resident, who pulled together the lament with his own musical voice, Rakena says.

"He plays a lot of instruments, bird sounds, various things to tell story. It carries, structured around the waiata Paulette and Komene composed, so the soundscape adds to the space, makes it immersive, so you go in there and bliss out."

The lament and music overlays video taken by cinematographer Iain Frengley (Ngāti Pākehā) on journeys with Rakena and Tamati-Elliffe up the river and to the deep lake. Filming underwater, they followed the journey of the mature tuna.

"She starts off in the deep lake and you can see native bush alongside as she travels. She dips her head up and down to look around, a device that we used to locate her specifically, although tuna can’t that see well."

Bringing the tuna alive is Donna Matahaere-Atariki (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Ruanui, Ngā Rauru, Te Ātiawa) who, dressed in a "haute couture" costume by Dunedin designer Amber Bridgman (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha), is filmed swimming through what is actually Dive Otago’s pool.

"I gave Amber a brief to make a haute couture underwater ruahinetanga [older woman] tuna costume, which we think she nailed."

That journey starts in a pristine water environment surrounded by native bush and birds, but then moves into areas with exotic trees like willow and a noticeable degradation in the water quality.

"Then you are confronted by the structure of the dam, and there is this jarring."

When the tuna reaches the concrete wall, the film switches to a bird’s-eye view of the dam, showing the difference between the water levels on each side.

Digital and video art director Michael Bridgman (Tonga, Ngāti Pākehā) post-produced the multi-screen video and soundscape and designed what the team call "the blockage", a long line of screens playing the video and emulating the wall of a hydro dam. It gives its name to the exhibition, "Ārai Awa", referring to the obstruction of the river.

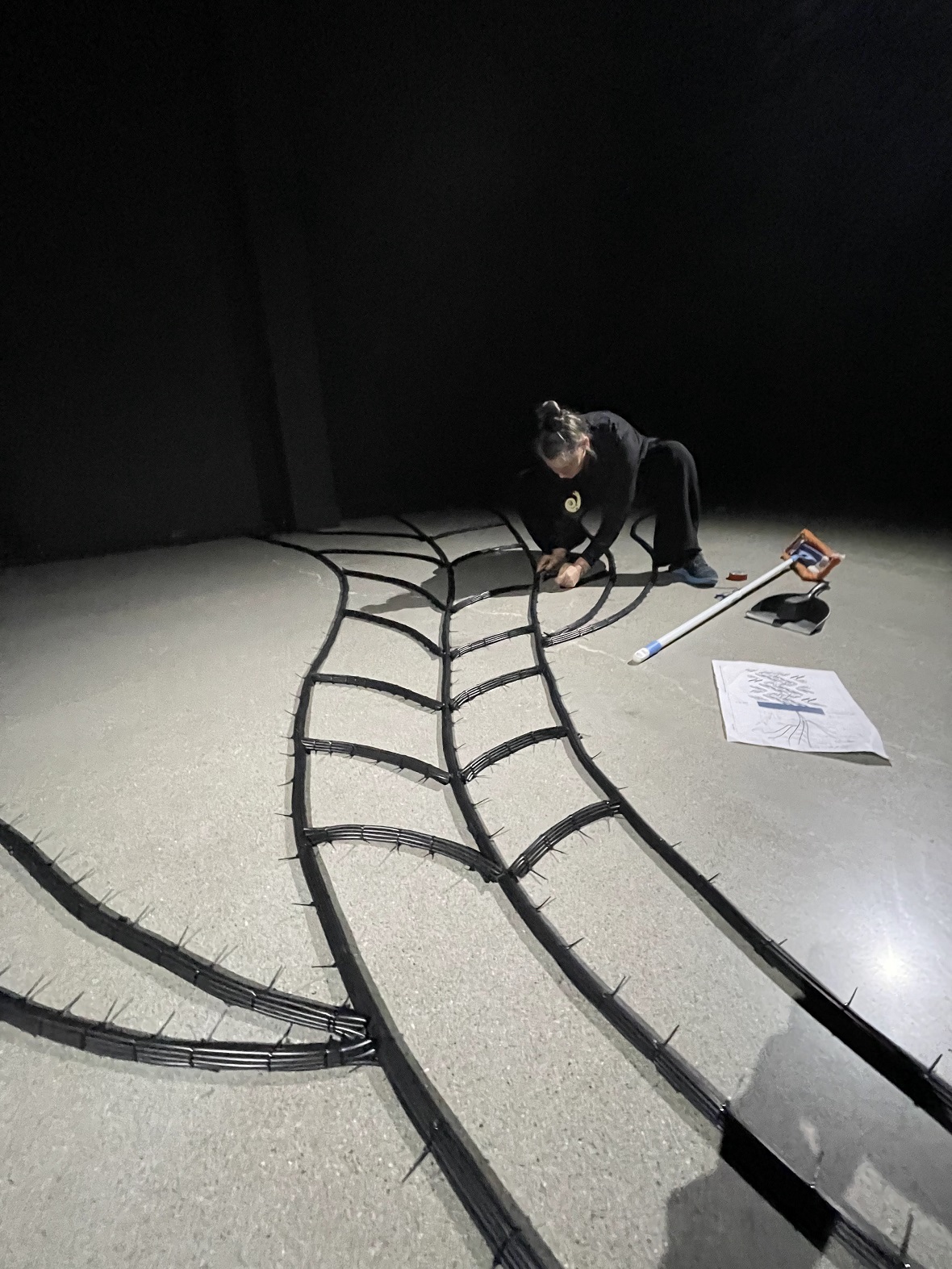

To illustrate the different water levels at the dam, artist Ross Hemera (Waitaha, Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāi Tahu), who has spent most of his life studying and drawing rock art, mostly in the Waitaki Valley, created a series of decals and used power cables and cable ties to create a taniwha work on the wall, giving a sense of freedom.

Rakena says the pattern on the "lake side" could be read in numerous ways, but there is a definite tuna among the ripple pattern, which is "sort of ambiguous".

On the other side the graphics seem to indicate a couple of tuna that have found their way out alongside the pattern representing the downstream power stations.

"Power cables literally plug the whole work into the world."

While various aspects of the work were created at different times and in different places, a small group of the artists came together for two weeks to install it as part of a residency with Te Atamira.

"I really like working with this group of people. This project brings together people who have been passionately engaged in their own practices for decades, this contribution brings together the best of that."

Cassidy agreed. "We have honed our skills and abilities, now to come together and work together, it felt effortless, working together was inspiring in itself."

The work is dedicated to Te Rau Aroha marae chairman William (Bubba) Thompson, who died just prior to the work being unveiled. Thompson was an instrumental figure in the elva trapping programme at Te Anau and had been working towards more research into the effects of the dam on fish passage.

Cassidy said it was very important for the group to acknowledge his work for tuna and the environment.

Te Atamira director Olivia Egerton said it was a wonderful opportunity for the Tahuna, Queenstown region to be able to showcase high-quality, world-class artists in its new arts and cultural space.

“We are delighted to present this installation, which highlights the fragility of our local environment, and the impact humans have on our ecosystems. It is extraordinary to have such an accomplished team of artists collaborating in this way, and if their mahi can provide a spark to bring more attention to this issue and a solution for our tuna, that would be a great thing.”

She described the work as "deeply immersive" and shining a light on a native species that lives in the water literally 250m from the gallery. Feedback has shown it is also drawing attention to other threatened flora and fauna as well.

TO SEE

Ārai Awa, Te Atamira, Queenstown, Until September 22, 2023