It does not matter if Jay Hutchinson is walking the streets of Dunedin or New York — his head will be down looking at the footpath.

"I’m constantly walking around looking at the ground," the Dunedin artist says.

While many artists are inspired by the sights and sounds around them, Hutchinson is only interested in the footpath, gutter or road verge — anywhere where society’s detritus collects.

Yes, Hutchinson is after our rubbish — the chip packets, drink cans, lolly wrappers, cigarette packets and fast food wrappers that float around city streets and country roads.

"We got off the plane in New York and my wife was pointing out the buildings and I was really excited I’d found this bright, colourful piece of American rubbish you wouldn’t get in New Zealand.

"She was like ‘typical, I’m looking at the buildings and you’re looking at your feet’."

And it is not just the item itself he has sought to re-create using his chosen medium — embroidery — but also the area it was found in.

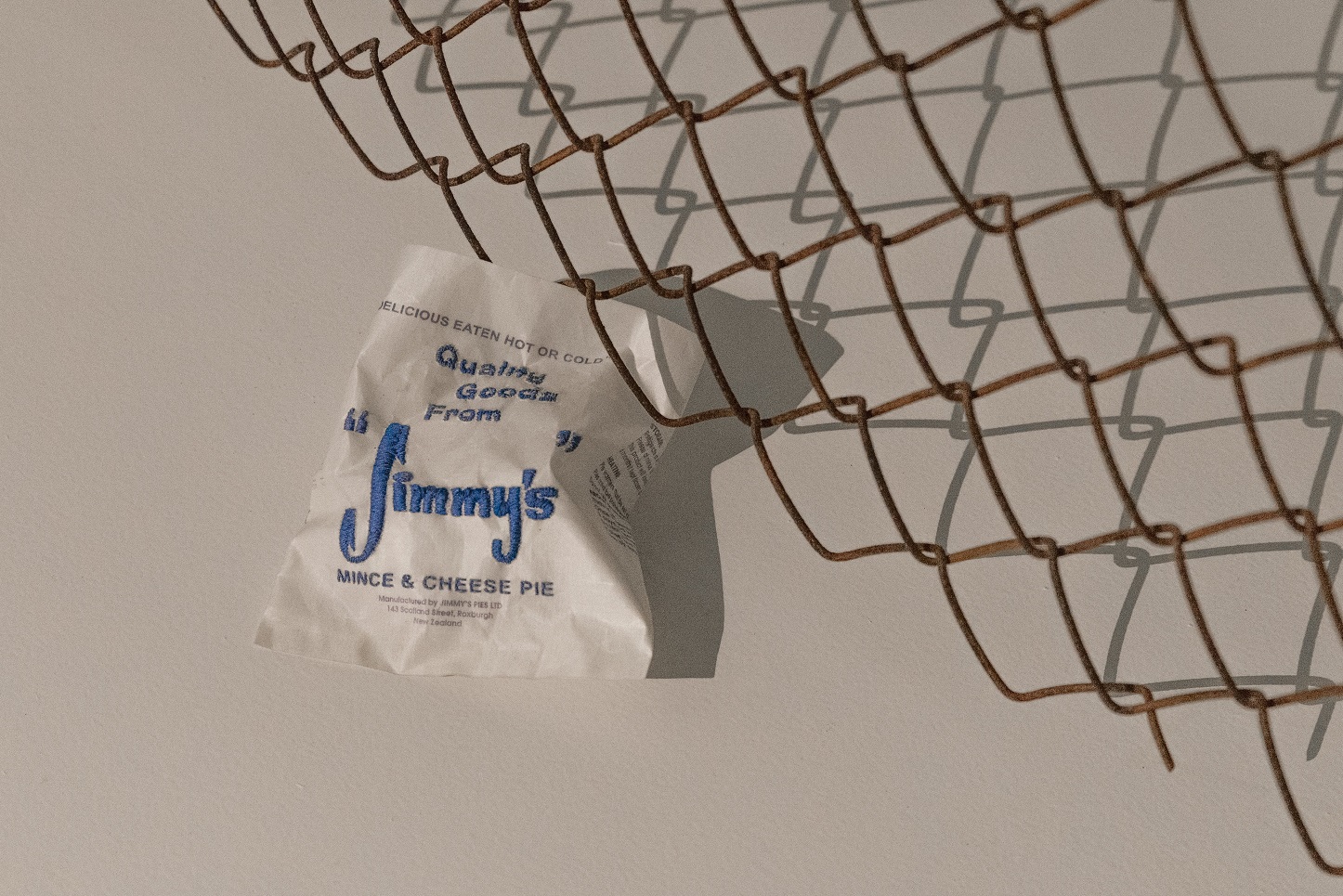

Like a hand-embroidered, digitally printed silk Jimmy’s mince and cheese pie wrapper, inspired by a wrapper of the Dunedin "icon" he found under a fence.

The Dowse Art Museum in Upper Hutt, a gallery known for pushing boundaries in what it displays and collects, purchased the work and the section of fence where it was found.

"Prepare to be enchanted, baffled, and surprised!” Dowse senior curator Chelsea Nichols says.

For Hutchinson, being showcased in the exhibition is pretty special, given he used to work for the Dowse as an exhibition technician. These days he lives in Dunedin and does a similar job for the Dunedin Public Art Gallery.

While admitting embroidery is not a common medium for a bloke, he says it comes with some serious advantages.

"It’s not like being in a cold, damp studio; it’s sitting in front of a fire with an embroidery hoop — a little bit different from some painting studios I’ve visited in Dunedin where you have 20 jackets on in the middle of winter."

He admits a lot of his friends made fun of him in the beginning because he was sitting around sewing.

"But now they generally all have my works on their walls or bother me when they have major birthdays."

Exhibitions of textiles are usually dominated by women, with Hutchinson often finding himself being the "token" male. He was the only male studying textiles in his year — or the one above and the one below him.

"Generally I don’t like to think of genderised things, but I was doing something different from what the women were doing, probably because of my age at that time."

It never really worried him as he started out doing a hairdressing apprenticeship. He had dropped out of school and with his parents urging him to get a trade, he, being a sensible teenage boy, followed the girls into hairdressing. He then decided to give art school a go in the late 1990s.

Hutchinson studied for a jewellery and textile diploma at the Dunedin School of Art, although what he really wanted to do was graffiti-style paintings, as he was still painting on the streets at the time .

"I ended up really liking textiles. I found my work was much stronger in textiles, so I slowly moved away from jewellery.

"That relationship with the street influenced my new work."

So he went on to do a bachelor in fine arts majoring in textiles, with screen printing and dyeing his focus, and making big, street-art-inspired pieces — such as in his first solo show in 2006, "Concrete to Textile" , in which he took graffiti from around Dunedin and re-created it in textiles.

"It was hand-stitching and staining the fabrics to re-create the surfaces."

After his undergraduate degree he had a year off "back washing dishes" and thought he "may as well" go back and do his master’s and take his art a bit more seriously.

"It taught me a really strong work ethic and good studio practice."

That was important for Hutchinson, as his work is mostly very portable, although when he first started he made large, hand-embroidered graffiti works.

"You can take it anywhere with you. I move into various rooms around the house like a cat following the sun."

The works begin with Hutchinson printing his photographs of the rubbish item on to fabric, and then he embroiders chosen details into it before he frames it.

"You’re trying to get them to sit the same way they’d appear on the street. That’s another heavily littered thing in Dunedin, the Jimmy’s Pie wrapper."

While he makes smaller works these days, the principles are the same. It is slow, methodical work, but he has got much faster over the years. Most of his works take between 20 and 100 hours to complete.

"I made a giant hand-embroidery My Little Pony years ago which used 21km of thread, a 1.5m by 1.5m giant My Little Pony.

"When I look back on it, I can’t work out why I decided to make a giant My Little Pony embroidery. For a while I got a lot of ‘brony’ jokes."

In the end he attributed it to his sister’s obsession with the toys when they were children.

"It was the least likely thing to make."

His inspiration comes from the streets he walks down. While in the early days he was on the lookout for graffiti, these days it is what gets left behind — whether in streets overseas, Nelson, or in Dunedin — that inspires him.

"I did one project looking at the rubbish on the streets, then the concrete underneath it.

Hutchinson has found rubbish is the same wherever he goes.

"In a trip to New York, McDonald's and Coca-Cola dominate the litter. Didn’t see any KFC litter in the States, though. You never come across health food; people don’t litter health food packaging. "

On that trip alone he collected 50 pieces of litter, but he had to cull it to 15 pieces to bring it home.

"Going though Customs you’re constantly wondering what they’re going to say about what’s in your bag. I’ve got bags of litter at home. Tidy Kiwi."

He always photographs the litter before he picks it up and showcases those pictures alongside his embroidery.

"So it has that context. I’m not just trying to show the product, but trying to show the dirty, screwed-up torn packaging, flashes of colour in the gutter.

"I’ve started to be interested in everything around them as well. It’s the compositions the streets make."

Canadian author Naomi Klein’s No Logo book, about how products and brands exist in the shop with what packaging surrounds them, and then continue to advertise and promote again — although for more negative reasons — in bins, gutters and streets, resonates with him.

"It relates to the environment and landfills, landfills are just crazy."

"In a lot of ways it rubbed off on us."

As a child of the 1980s he remembers the days before mass production dominated the country’s purchasing.

"Textile work is about time. It takes time to make it, filling in one stitch at a time while people like things fast these days — fast food, fast fashion, everyone is in a hurry, whereas with embroidery or hand stitching it slows everything down."

One of his recent projects is a play on Otago-based literary magazine Landfall. Hutchinson’s magazine is called Landfill, and is a mix of essays by local writers and his own textile and photographic works.

"My phone is full of rubbish photos. You’ve really got to search to find photos of my cat or my wife, who doesn’t like photos. It’s seriously ridiculous."

The other Dunedin artist featured in the Dowse exhibition, McIntosh, is also known for her quirky works, made out of vintage underwear and bits and bobs.

Her work My Handbag, My Choice was created in support of abortion reform in New Zealand, and features beige underwear found in op shops, freshwater cultured pearls, a found clasp, knitting needles and crochet hooks.

"Foundation garments are created with the express purpose to shape and control the body, so there seems no more fitting receptible to create a handbag that discusses bodily autonomy and reproductive rights."

TO SEE

Unhinged: Opening the Doors to the Dowse Collection, Dowse Art Museum, Wellington, until August 13.

!["Flux" featuring Portraits of Geoff Dixon (2021–2025), acrylic on paper [installation view], by...](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/story/2025/07/1_macleod.jpg?itok=ywgJww50)