There are many reports based on scientific research that talk about the long-term impacts of climate change — such as rising levels of greenhouse gases, temperatures and sea levels — by the year 2100. The Paris Agreement, for example, requires us to limit warming to under 2degC above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century.

Every few years since 1990, we have evaluated our progress through the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) scientific assessment reports and related special reports. IPCC reports assess existing research to show us where we are and what we need to do before 2100 to meet our goals, and what could happen if we don’t.

The recently published United Nations assessment of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) warns that current promises from governments set us up for a very dangerous 2.7degC warming by 2100: this means unprecedented fires, storms, droughts, floods and heat, and profound land and aquatic ecosystem change.

While some climate projections do look past 2100, these longer-term projections aren’t being factored into mainstream climate adaptation and environmental decision-making today. This is surprising because people born now will only be in their 70s by 2100. What will the world look like for their children and grandchildren?

AFTER 2100

In 2100, will the climate stop warming? If not, what does this mean for humans now and in the future? In our recent open-access article in Global Change Biology, we begin to answer these questions.

We ran global climate model projections based on Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP), which are ‘‘time-dependent projections of atmospheric greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations’’. Our projections modelled low (RCP6.0), medium (RCP4.5) and high mitigation scenarios (RCP2.6, which corresponds to the ‘‘well-below 2 degrees Celsius’’ Paris Agreement goal) up to the year 2500.

We also modelled vegetation distribution, heat stress and growing conditions for our current major crop plants, to get a sense of the kind of environmental challenges today’s children and their descendants might have to adapt to from the 22nd century onward.

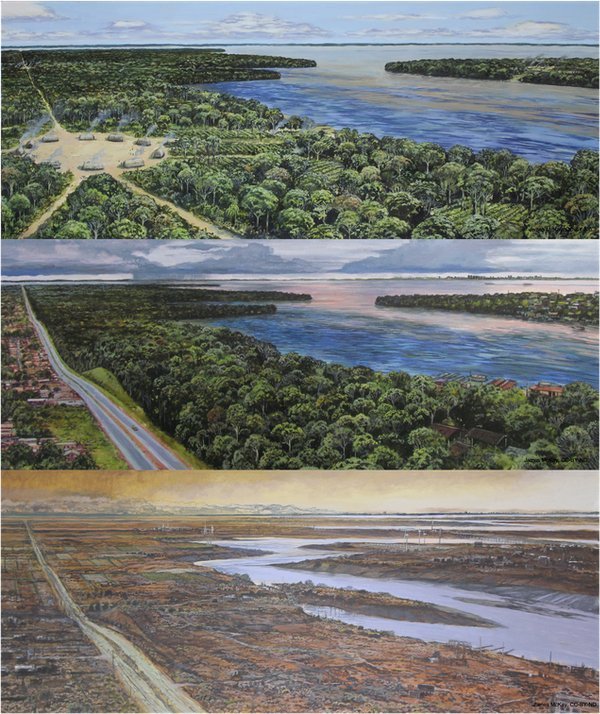

In our model, we found that global average temperatures keep increasing beyond 2100 under RCP4.5 and 6.0. Under those scenarios, vegetation and the best crop-growing areas move towards the poles, and the area suitable for some crops is reduced. Places with long histories of cultural and ecosystem richness, such as the Amazon Basin, may become barren.

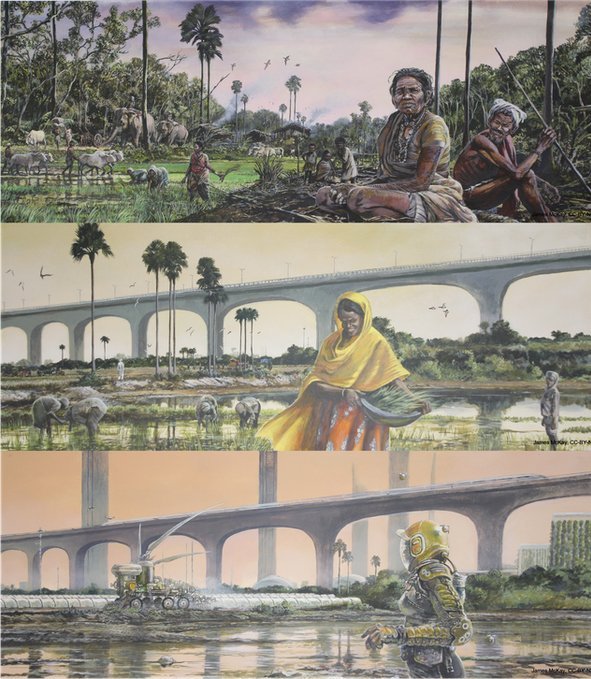

Further, we found heat stress may reach fatal levels for humans in tropical regions that are currently highly populated. Such areas might become uninhabitable. Even under high-mitigation scenarios, we found that sea level keeps rising due to expanding and mixing water in warming oceans.

Although our findings are based on one climate model, they fall within the range of projections from others, and help to reveal the potential magnitude of climate upheaval on longer time scales.

To really portray what a low-mitigation/high-heat world could look like compared to what we’ve experienced until now, we used our projections and diverse research expertise to inform a series of nine paintings covering a thousand years (1500, 2020, and 2500CE) in three major regional landscapes (the Amazon, the Midwest United States and the Indian subcontinent). The images for the year 2500 centre on the RCP6.0 projections, and include slightly advanced but recognisable versions of today’s technologies.

AN ALIEN FUTURE?

Between 1500 and today, we have witnessed colonisation and the Industrial Revolution, the birth of modern states, identities and institutions, the mass combustion of fossil fuels and the associated rise in global temperatures. If we fail to halt climate warming, the next 500 years and beyond will change the Earth in ways that challenge our ability to maintain many essentials for survival — particularly in the historically and geographically rooted cultures that give us meaning and identity.

The Earth of our high-end projections is alien to humans. The choice we face is to urgently reduce emissions, while continuing to adapt to the warming we cannot escape as a result of emissions up to now, or begin to consider life on an Earth very different from this one. — theconversation.com

- Contributors are Christopher Lyon, McGill University; Alex Dunhill, University of Leeds; Andrew P. Beckerman, University of Sheffield; Ariane Burke, Université de Montréal; Bethany Allen, University of Leeds; Chris Smith, University of Leeds; Daniel J. Hill, University of Leeds; Erin Saupe, University of Oxford; James McKay, University of Leeds; Julien Riel-Salvatore, Universite de Montreal; Lindsay C. Stringer, University of York; Rob Marchant, University of York; Tracy Aze, University of Leeds.

Comments

It is the deepest of moral failures to casually saddle today’s young people with a critical task that may prove unfeasible by orders of magnitude – and expecting them to somehow accomplish this amid worsening heatwaves, fires, storms and floods that will pummel financial, insurance, infrastructure, water, food, health and political systems. - Peter Kalmus, Climate Scientist.

The population of the planet has increased from around one billion to eight billion over the last 200 years. The consequences of this can be seen in climate change. The population is expected to continue to increase. Most of this will occur in resource poor countries. Unless the population of the planet is reduced or at least does not increase, any efforts to reduce the effects of human activity will be futile. If you are serious about reducing the effects of humans on the environment the biggest contribution you can make is to have no children. This will have the two fold benefit of freeing you from guilt and if not yours, at least giving the polar bear a chance to pass on its DNA.

This is the type of ill-informed logic that makes my skin crawl!

Most countries already have below replacement birth rates

Japan has already passed peak population (228m in 2017) and is projected to fall to 53m by 2100

China will drop from 1400m to 732m, India will remain about the same and Bangladesh will drop from 157 to 81

Western countries will most likely increase even though their birth rate is sub replacement because they will accept skilled migrants and skilled people will want to live there

Africa is where there will still be a birth rate driven increase because they are still mostly poor

Current UN projection is that we will reach 11 billion but the medical journal, Lancet project "world population will likely peak in 2064 at around 9.7 billion" & be "about 8.8 billion by 2100"

The key is to increase the wealth of Africa, not the voluntary genocide of developed countries

The best way to do that is to develop LIMITLESS CHEAP ENERGY in a functional democracy

The best way to do that is to have children in a stable family, instill in them a passion for the planet and humanity, then educate them in physics, chemistry and engineering

The real problem is that we have lots of wishful thinkers who ignore reality. The United Nations Population Division (2019) projects “peak human” reaching 11 billion by 2075, 3.2 billion more than today.This of course assuming everyone cooperates. History has shown that this does not tend to happen. Unfortunately the reality is that the world isn’t all motherhood and apple pie.

Sirius, you need to embrace factfullness

Most of the projected population growth is currently locked in as increased life expectancy

I imagine you are part of that growth

Hans Rosling did a lot of good work on this topic before his death

I'd suggest to watch some of his presentations or get his book Factfullness

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FACK2knC08E

Climate change isn’t caused by population growth. It’s caused by greenhouse gas emissions primarily from burning fossil fuels and the destruction of carbon sinks.

A small minority of wealthy people produce the majority of global greenhouse gas emissions — their consumption habits have a much greater impact than overall population numbers. It’s true that the planet can’t support unlimited population growth but if people can figure out how to moderate our consumption and meet our needs without fossil fuels and protect/restore the natural environment including biodiversity, experts say, it is possible for all of us to live sustainably and well — even if there are more of us.