Glenn Blundell is just back from an exercise class. He is 58 and lives in a modest retirement village in friendly, laid-back Mosgiel. Right now he is standing in his lounge, talking to a friend who has popped over.

It sounds idyllic.

But that is far from reality.

"I’ve got COPD," he says matter-of-factly about the irreversible chronic inflammatory disease that obstructs airflow from his lungs.

On a good day that tank, that tube, ensures enough oxygen is flowing through his failing lungs to keep him mobile and alive. But when cold, calm conditions trap fireplace pollutants in the Mosgiel air, Blundell is in trouble.

"You can smell it when it’s not good," he says.

"That means I can’t go outside because the oxygen levels in my blood go down."

It was like that last week. Mid-week, dropping temperatures encouraged people to light their fires while an inversion layer trapped the minute, smoky, carbon particles in the air that hung in the town basin. On the Wednesday, the pollution pushed above the national air safety guidelines, the fourth time it had done that in Mosgiel during the past two months. The next day it almost breached again.

Blundell had not noticed and had gone out for some of the regular exercise vital for people with COPD.

"I walked to the car but had to stop and take a breather," he says.

He is not the only one concerned.

Local and national experts in air quality, domestic heating and public health are shocked by the Otago Regional Council’s decision to halt its air quality improvement work for four years. They are dismayed the council has made that decision despite the fact that some Otago towns rank among the worst for air quality in New Zealand, the region is already lagging behind on air quality improvements and some citizens’ health will suffer (perhaps resulting in hospitalisation, if not worse).

Otago is regularly "top of the pops" for poor air quality, Dr Ian Longley says.

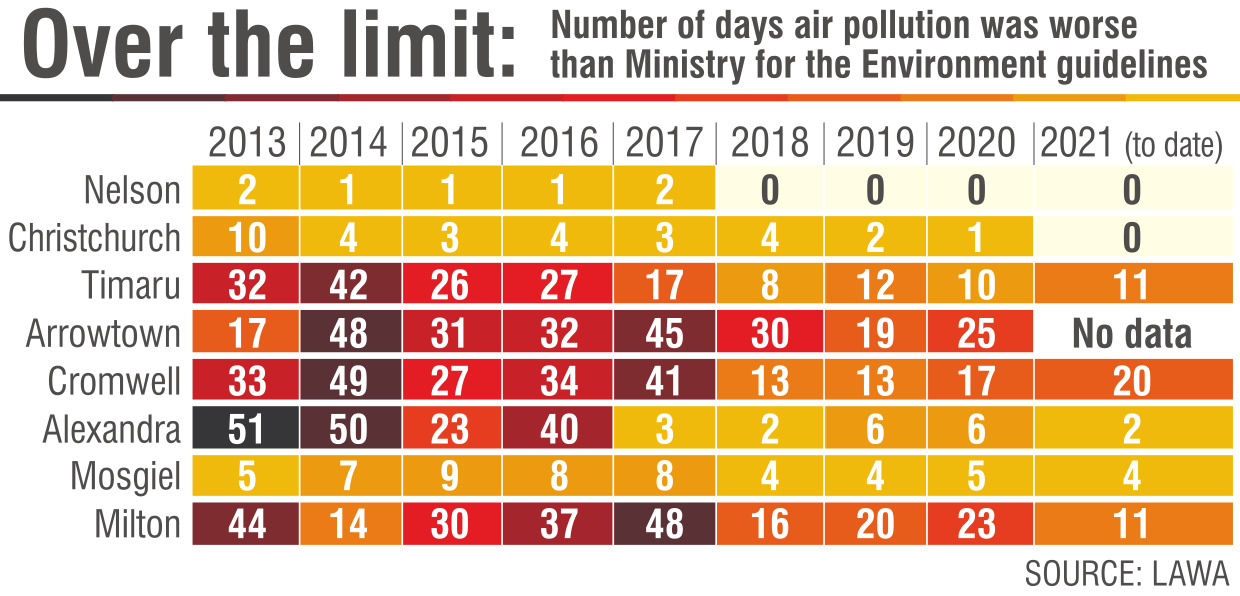

Last year, Arrowtown exceeded the air pollution safety guidelines 25 times, Alexandra six times, Mosgiel five, and Milton 23. This year Cromwell has exceeded it 20 times, with a third of winter still to come.

Almost all of that air pollution is coming from domestic solid fuel burners, household fires.

"When you look at the most polluted towns in the country, they are consistently from South Canterbury down," Dr Longley says.

"Over the last 10 years, the further north you go, air quality has generally improved in a way that it hasn’t really in Otago."

Otago’s track record of trying to improve air quality in towns susceptible to inversion layers is chequered. There have been improvements. A decade ago, a number of those towns were having 30, 40, 50 breaches a year. Now they are occurring between four and 25 times a year. Less positively, during the past couple of years, "exceedences" have been holding stubbornly steady or tracking upwards.

The ORC’s efforts to implement the 2005 national air quality guidelines were embodied in its 2009 Air Plan. That air plan has been updated. In 2017, the council also had a go at developing an air strategy. But that only reached pilot stage before being deemed too expensive and shelved.

The council has monitored air pollution in 13 Otago towns, not counting Dunedin, but has reduced that to six — Arrowtown, Alexandra, Clyde, Cromwell, Mosgiel and Milton. Until last year, it also operated a Clean Heat Clean Air subsidy programme that helped homeowners replace non-compliant burners with low-emission appliances. But that stopped at the end of last year.

Then, at the start of this month, as part of its 2021-31 Long Term Plan, while affirming that its top priorities were water, biosecurity, biodiversity, transport and air, the council confirmed that because of "budgetary pressures" it would be "pausing most of our air quality work".

The response has been a mix of surprise, anger, ironic laughter and a little bit of understanding.

Dr Longley says the ORC’s air plan has not made much headway, so it makes sense for it to revise its plan. But the news that on-the-ground improvement work would halt in the meantime was unexpected.

"We were all a bit shocked when we heard that," he says.

Dr Jeremy Baker calls the decision "a shocking abrogation of their duties under the RMA".

"It is alarming that the ORC seems to view its duties around air quality as optional," Dr Baker, who is the executive director of Cosy Homes Trust, says.

The trust, which promotes healthier housing in Otago, previously had a contract with the ORC and has one with the Energy Efficiency & Conservation Authority.

"Funding pressure is not an acceptable excuse for failing to carry out one of its principal responsibilities — one that was put in place to protect human health," Dr Baker adds.

"Did they really use the word ‘pausing’?" the Wellington-based University of Otago housing and health researcher asks.

"It’s like saying you can pause breathing after you’ve passed out.

"Just saying we don’t have the capacity is unacceptable from a public health point of view."

Health impacts are at the heart of the concern.

The tiny carbon particles from wood and coal fires, when inhaled, lodge in airways or end up deep in people’s lungs.

The effect builds with time, Dr Longley explains.

"For as long as nothing is done, people are exposed to this poor air quality. It has a cumulative effect, particularly on people with compromised lungs, the young, pregnant women — they’re all at risk. The longer that goes on, the more health problems stack up."

Those problems can include decreased lung function, heart attack and death.

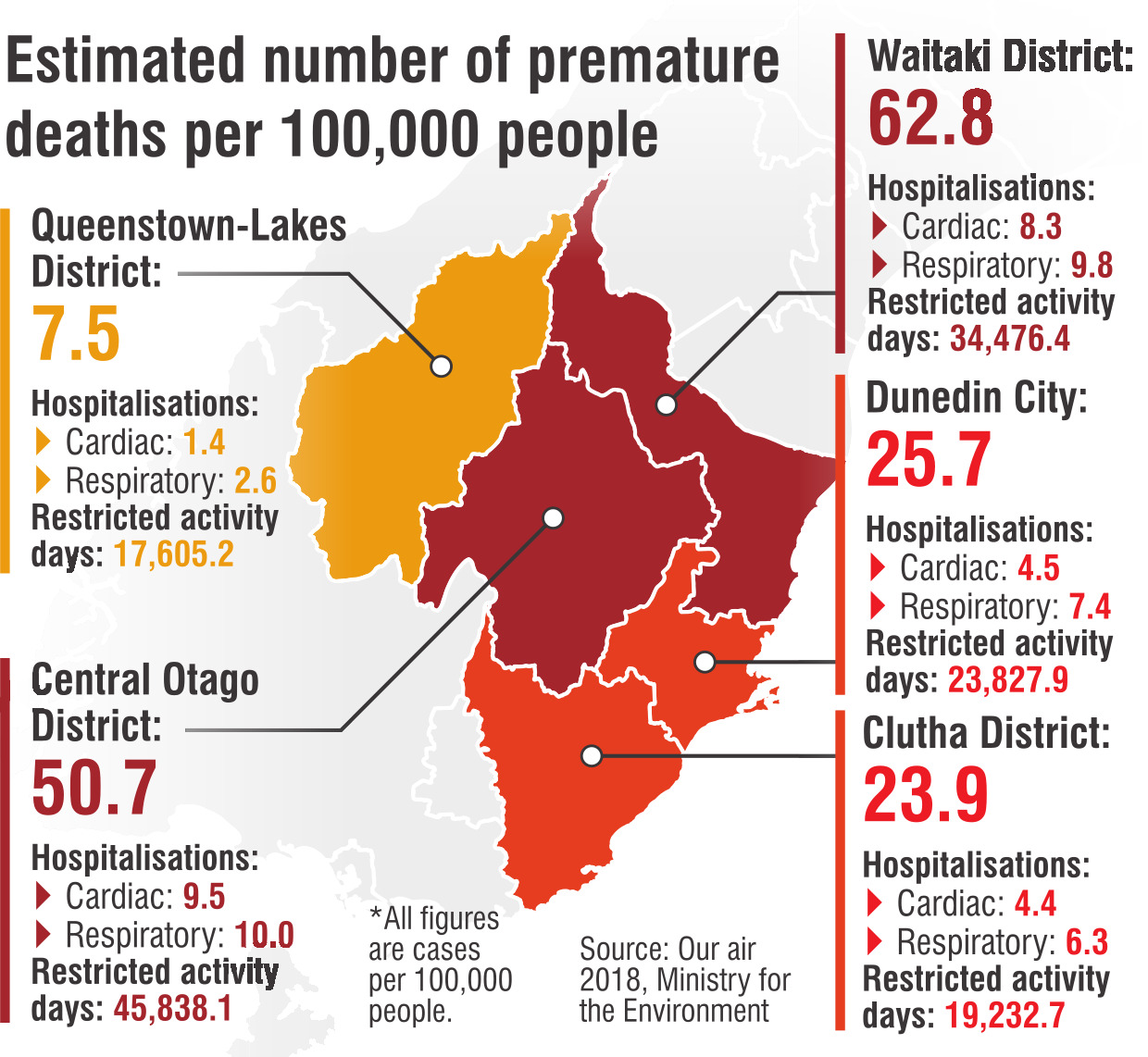

The latest figures available, compiled by the Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand, estimate that in New Zealand, in 2016, air pollution from human-made PM10 particles resulted in 1.49 million restricted activity days, 440 respiratory hospitalisations, 236 cardiac hospitalisations and 1277 premature deaths.

Nationally, PM10 pollution prematurely kills 27.2 people per 100,000 people. In Central Otago it is 50.7 per 100,000 and in Waitaki District it is 62.8 per 100,000, more than double the national average.

"If you aren’t going to take proactive steps to fix it, then that’s one of the consequences you are going to have," Prof Borman, who heads up Environment Health Intelligence New Zealand, which provides data and analysis to the Ministry of Health, says.

"Obviously, it is not as high a priority as some other things in their [ORC’s] area. That’s their decision, but the fact of the matter is that bad air quality is related to adverse health outcomes."

Blundell now knows that only too well.

He grew up breathing the smoggy air of 1960s Christchurch. On top of that, the former restaurant cook smoked for 30 years.

He gave up cigarettes seven years ago; not long after his condition was diagnosed.

"About 25 years ago I was told I had asthma," Blundell recalls.

"I’d never heard of COPD until I came to Dunedin.

"I was getting breathless ... They x-rayed my lungs and said you’ve got COPD."

Blundell has had to stop working. He has been told that without a double lung transplant he has less than two years to live.

The ORC agrees "the link between air quality and human health has been well established".

That is a quote from its 2021-31 Long Term Plan. It is the same sentiment that has been in ORC annual plans for years. It is the same freshly-minted Long Term Plan that also states "due to funding pressures, we are pausing most of our air quality work".

Asked by The Weekend Mix whether pausing this work was acceptable, ORC chair Andrew Noone acknowledged in an emailed response that air quality had not been prioritised since the subsidy ran out and that water management was the current priority.

Cr Noone says the new air plan will include air quality implementation funding that increases from $1 million per year in 2024-25 to $3.5 million per year from 2026-27 onwards.

On the question of whether the council had been proactive enough over the years, Cr Noone said lots had been done but there was room for improvement.

"ORC has undertaken considerable investment in air quality, including through stringent rules, involvement in the Cosy Homes Trust, and provision of subsidies," he says.

"Despite this, we acknowledge that more is needed and this is reflected in the review of the Air Plan commencing in Year Two of the Long Term Plan.

"More can be done, and ORC will be looking into a multi-agency, multi-pronged approach rather than just relying on regulations."

Gwyneth Elsum, the ORC’s general manager of strategy, policy and science, expands on that.

"ORC recognises that a multi-pronged approach is needed to address more of these factors," Elsum says.

"As part of the air plan review, ORC will be drawing from the success of other regional councils’ approaches, such as Environment Canterbury."

Canterbury has done well on some fronts - Christchurch is certainly much improved - but Nelson is the star performer, air quality experts say.

"Nelson used to have 78 exceedences a year, now it’s zero. It’s so great," Lou Wickham says with enthusiasm.

Wickham, who is senior air quality specialist with consultancy Emission Impossible, has some sympathy for ORC’s situation.

Firstly, the climate, terrain, and meteorology of Otago makes air pollution more of a problem in some towns. Then there is the task of getting homeowners to stop using coal and install new burners or electric alternatives.

"It’s hard-going because ... nobody likes to be told what to do, particularly in their own home."

But at the same time, the secret ingredient for councils throughout New Zealand is "hard graft", Auckland-based Wickham says.

That is what Nelson has been so good at, Wickham says.

"The council did a lot of work on changing out burners, putting in timelines, assisting people to insulate homes and providing grants for efficient burners or to change to heat pumps."

Nelson did not spend more money than others, but it did a lot of education and advocacy work.

"Mostly it was hard graft."

It is an area where the ORC has perhaps let itself down, Dr Longley suggests.

"You know, really reaching out to the public, making sure they are aware of what is available, making sure the installers are doing their job properly ... that whole sort of marketing push is what I think Nelson did pretty well," Dr Longley says.

"Sometimes, talking to people in places like Arrowtown, Cromwell and Alexandra, they say, ‘Well we’ve never seen people from the regional council, they don’t come over from Dunedin’."

For Blundell, change might come too late.

He is in line for a double lung transplant. But absence of family to help immediately after the operation might mean that never happens.

Without a transplant, exercise might keep his lungs going for a couple more years.

But getting out and about is impossible when air quality is poor.

"Walking is prolonging my life a little bit. It might give me two years rather than one," he says.

"Better air would make a heck of a difference."

bruce.,munro@odt.co.nz

Comments

I just got my second 'fixed' power bill increase a couple of weeks ago for this winter. Up now to a total of 5c/kW or 29% year on year- but the government says inflation is only 2-3%. I wonder if there is a correlation? where people are using wood to keep warm instead of electricity because of the cost?

Bad as this is, the ORC is not the only only to blame. People know their fires are smoking, they know when an inversion layer has formed and they still light it up. Its been years since the link between bad air and bad health was established. Even around here, people bank up there fires and let it smoke out the neighborhood. Coming up Brockville Rd, its not unusual to walk into a plume of smoke from one or two homes that has drifted a few hundred meters down the hill. It's not ignorance at this point, its indifference.

Poor education, poor air monitoring and poor people. But most of all a poor regional council.

So what do they want to happen?, people quitting their wood burners and going electric heating when electricity costs are ever rising and people putting off food buying to pay the electric bill.....

Millions of dollars have been spent by councils to improve the microbiological quality of Otago rivers for bathing and exploring new office buildings. Bathing is a consensual pursuit that involves some risk of a stomach upset to the relatively small number of people brave enough to venture into Otago’s “freezing “ rivers. Breathing is involuntary, everyone does it. Poor air quality affects everyone without exception and can be life threatening to people with asthma, heart or breathing issues. The healthy are also affected as breathing of poor air can cause a range of serious life threatening diseases to develop. We need councils that are capable of prioritising serious environmental issues and making sensible decisions. Unfortunately Otago have non of them. I wonder what the $20,000,000 spent so far on offices and the hundreds of million of dollars spent on stadiums etc could have done for the health and safety of Otago’s people?

Good comment.

This and a 49% increase in rates? So what are we getting for our money?