Flying a lot undermines our collective commitments to the Paris Agreement, and personal efforts to decarbonise our lifestyles.

A rapid return to pre-Covid levels of international tourism when borders reopen is a priority for industry organisations such as the UN World Tourism Organisation and the World Travel and Tourism Council. Yet decarbonising air travel is impossible in the absence of technology innovations that do not exist as a solution to high aviation emissions.

A critical question for aviation is whether people could, or should, fly less. This question received global attention when it was raised by the Fridays for Future movement and the mainstream media’s reporting on ‘‘flight shame’’ in early 2019.

The Guardian newspaper summarised the dilemma:

‘‘When scientists say that we must make ‘rapid, unprecedented change’ to our lifestyles to avoid climate catastrophe, and pinpoint flying as the most destructive form of travel, the questions mount: Is there such a thing as a right to fly? Is self-sacrifice necessary? Can you fly with a conscience? Are ‘love miles’ to see family or friends OK?’’

At present, the necessity of air travel and the importance of flights taken are questions that are ignored or resisted by the majority of air travellers. In fact, the dominant neoliberal economic system actually encourages excessive air travel. But the need to fly cannot remain unquestioned when we need to act urgently to decarbonise our economy and society.

Our research asked study participants in Europe confronting questions about their air-travel behaviours over the past six years, and the necessity of flights they had taken. All our study participants conceded they had taken flights that in hindsight they considered to be unnecessary or, in some cases, completely wasteful. They were easily able to distinguish between flights they considered ‘‘important’’ or ‘‘necessary’’, and flights that were ‘‘spontaneous’’ and ‘‘superfluous’’.

Their honest responses to our questions revealed diverse views on the perceived necessity of air travel, revealing that different types and purposes of air travel are not equal. Rather, the importance of air travel depends on a wide variety of factors that include the reasons for travel, the distance and availability of alternative travel modes and social factors, including prestige and social media status.

It emerged that a lot of air travel is triggered by irresistibly cheap seats that are bought spontaneously with little consideration given to the actual purpose or need to travel. This suggests that steps can be taken to reduce or eliminate superfluous flights. Ensuring that the environmental costs of flying are built in to the cost of flights is one such step. This is exactly what Simon Upton, the Parliamentary Commissioner for Environment, recommends in his recent report on sustainable tourism.

We found that that flying for social purposes such as visiting friends and relatives, or visits home, and for educational reasons, are likely to endure while unimportant flights may gradually ‘‘disappear’’ in the context of stronger policies to mollify aviation demand.

Every part of our society and economy must be accountable to climate action. Air travel is no exception. Covid-19 has presented a unique opportunity to restructure the airline industry, to achieve a climate-safe alternative to high-volume, high-carbon tourism. Within this context, our recent research has investigated the role that airline marketing communications play in driving high demand for air travel.

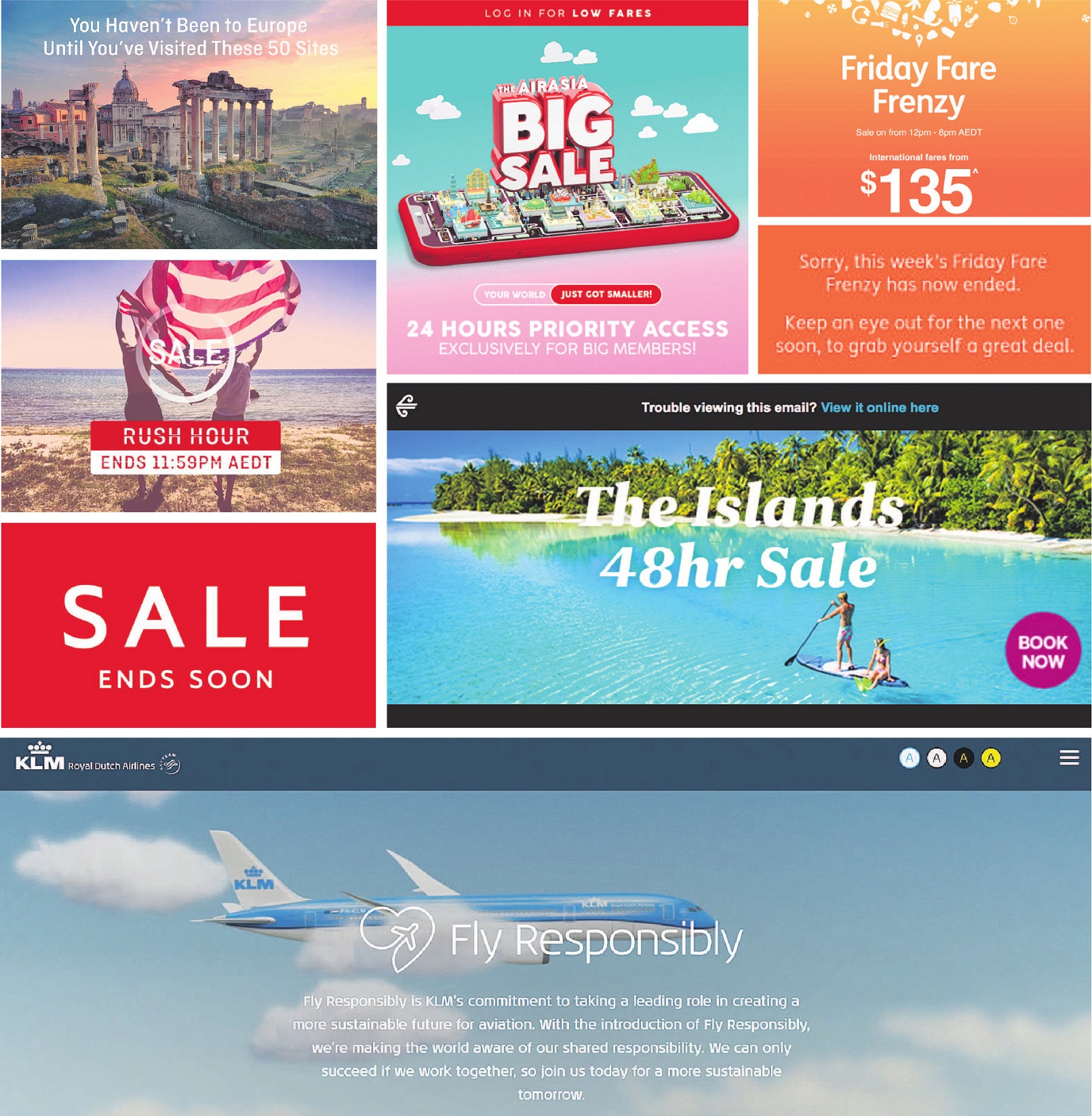

Analysis of the online marketing communications of selected national carriers and low-cost airlines revealed three prominent tropes. We found that airlines use privilege and exclusivity to construct cultural capital by conferring prestige and class distinction. Airline marketing communications also use strategies to create a sense of urgency and fear of missing out on cheap flights. Time is deployed artificially through explicit references to closing flight sales and limited seat availability to create a sense of supply disruption and give the impression of resource scarcity.

Beyond stimulating demand, airline marketing communications encourage moral disengagement by promoting the personal benefits of air travel, while downplaying or suppressing the ethical elements of consumption. From a consumer perspective, persuasive airline advertisements activate the desire for carbon-intensive lifestyles, which actually contradict the environmental values of most consumers.

Recent developments in Europe offer the first signs of post-Covid aviation regime change. The French Government has attached ‘‘green conditions’’ to bailout terms for Air France requiring an end to services on domestic routes that compete with high-speed rail. We also see emerging evidence of ‘‘green shoots’’ in some airline marketing campaigns. The KLM ‘‘Fly Responsibly’’ campaign introduces a social marketing nuance that mirrors efforts to reduce alcohol harm. It suggests that ‘‘...a flight [drink] or two is fine, but moderation is required to avoid flying [drinking] too much’’.

Of course, these questions strike at the heart of consumer culture and freedoms to consume that will be resisted by many. The importance ascribed to flying varies between individuals, between individuals and society, and between societies. But the important question remains: Can we find ways to fly less and to fly more responsibly?

- James Higham is a professor in the department of tourism at the University of Otago, and is a member of the He Kaupapa Hononga advisory group. Each week in this column, one of a panel of writers addresses issues of sustainability.

Comments

There is no point in hand wringing ... the problem is the world is overpopulated with billions of people with material aspirations - all laudable in the individual, but unsustainable in total.

Cheap fares are a distractor - they are offered to fill aircraft that are going to be flying that route anyway. The base carbon cost of flying is trivially increased by having you in an otherwise empty seat.

No problem with flying as soon as it is feasible. I look forward ti being able to visit other parts of the world with a clear conscience. Time to start ignoring these hand wringing, holier than thou, pessimists.

Sally Weintrobe - “Psychological Roots of the Climate Crisis” states its argument in its subtitle: “Neoliberal Exceptionalism and the Culture of Uncare.” Weintrobe writes that people’s psyches are divided into caring and uncaring parts, and the conflict between them “is at the heart of great literature down the ages, and all major religions.” The uncaring part wants to put ourselves first; it’s the narcissistic corners of the brain that persuade each of us that we are uniquely important and deserving, and make us want to except ourselves from the rules that society or morality set so that we can have what we want. “Most people’s caring self is strong enough to hold their inner exception in check,” she notes, but, troublingly, “ours is the Golden Age of Exceptionalism.”