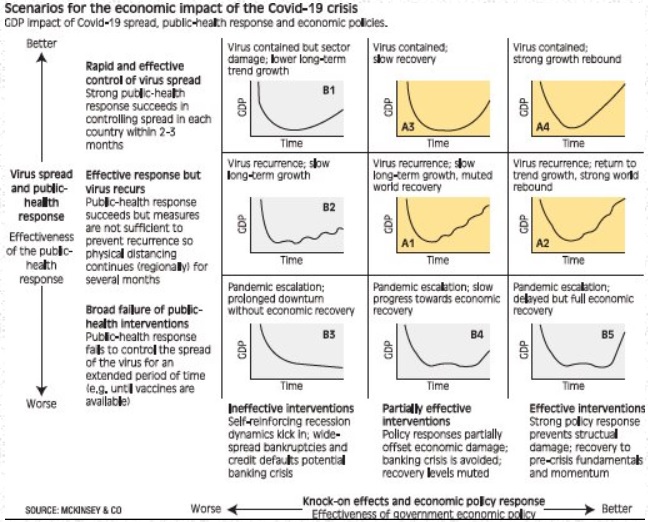

Tens of billions of dollars are being pumped in to the New Zealand economy to save lives, jobs, homes and businesses threatened by the Covid-19 pandemic. Will the country be left crippled by huge, long-term debt? Bruce Munro finds a surprising, heartening answer.

The chance of the All Blacks running on to the paddock at Marvel Stadium, in Melbourne, on Saturday, August 8, for the first Bledisloe Cup match of 2020 looks slim.

Here at the mid-point of the third week of New Zealand’s nationwide pandemic lockdown, with the global number of Covid-19 confirmed cases and deaths heading towards two million and 110,000 respectively, we could do with a distraction to look forward to. A transtasman rugby test would be just the ticket, unlikely as it is.

But just imagine if it did take place, Australian economist Professor Bill Mitchell says.

The national anthems, the haka, the crowd roaring at the kick-off ...

Midway, the All Blacks are trailing by just one point. The two teams come back on for the second half. We settle back on a million couches in a million Kiwi living rooms, eager for another 40 minutes of exciting game time.

Two minutes in to the second half, Beauden Barrett slots a penalty against Australia. But the scoreboard does not change. The players look confused. The referee listens to an unheard voice in his ear, then blows hard on his whistle and throws his arm in the air. The game is over.

Why? Because the electronic scoreboard has run out of numbers, the referee explains.

"That’s crazy", the nation collectively yells at the referee on myriad TV screens.

"It’s an electronic scoreboard. It can’t run out of numbers!"

It is a ludicrous scenario, agrees Prof Mitchell, who then delivers his punchline.

"The Budget is just the Government’s scoreboard. It can put up whatever number it wants," he says.

At the time, it was announced as a $12.1billion response package. The Government said the huge figure was needed "to cushion the impact of Covid-19 in the fight to support Kiwis’ jobs and the domestic economy from the virus" and called it "the most significant peactime economic plan in modern New Zealand history".

The money would be spent on boosting health services, loans to businesses, wage subsidies, mortgage holidays and welfare benefit increases.

A week later, multinational financial services company KPMG said the package had been expanded and was "now expected to cost approximately $17billion to $18billion".

"This Bill will approve capacity for $52billion of spending on our immediate Covid-19 response. It's about the massive economic cost of this exercise," Finance Minister Grant Robertson told Parliament.

"Fifty-two billion dollars, which is about 17% of GDP as it was before the crisis. It might be a higher percentage now, who knows?" Goldsmith replied in support.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern was clear about what was being done and why.

“The Government is pulling out all the stops to protect the health of New Zealanders and the health of our economy,” Ardern said.

Her finance minister framed the cost as enormous but necessary.

"The scale of the spending is the price that we have to pay," Robertson said.

"It's the price of making sure our public health system can operate and support New Zealanders. It's the price of people keeping their jobs and keeping their homes. It's the price of cushioning the blow to businesses and of keeping them afloat, and it's the price of making sure that the core of an economy exists that we can build on to recover in the way that New Zealanders want us to do."

"Generations will be paying for it, that's the truth," he said in a radio interview.

"The massive investment we are making and that other countries are making ... will take many years to deal with. That's why we have to have a plan for what the economy looks like ... [one] that allows us to pay debt back, have taxes at a reasonable level and allows us to maintain living standards."

It will be a big burden, but manageable, he says.

"I [pay] tribute to Bill English and Sir Michael Cullen, in particular, as finance ministers who ensured that we were ready for the rainy day. It's arrived; it's pouring, ladies and gentlemen, and we need to make sure we build off the benefits of that disciplined work that came before us, and indeed that of this Government during our two years."

Others agree.

Goldsmith again: "We can do it because we’ve saved for it; eye-watering figures which New Zealanders can pay because of the careful stewardship of previous governments, both Labour and National."

This is the dominant narrative among politicians and economists.

But it is not the only one.

There are those who say previous governments’ austerity is irrelevant to our current predicament and, if not irrelevant, then harmful. They say good governments need to spend to benefit their citizens and can do so without damaging the economy. They say government deficits are not the arch-enemy of personal prosperity we are constantly told they are, in fact, the opposite is true. They add that we have had the wool pulled over our eyes for too long and need a fundamentally different understanding of the government’s role in the economy; a view that says the "biggest blank cheque in the history of the country" need not give us a single sleepless night.

Do we need to be worried about all that debt?

"Not at all. Why would anybody be worried about it?" he replies.

"The New Zealand Government issues its own currency. So ... financially it never has to default on any of its liabilities as long as they are in that currency.

"We’re always talking about government debt as if it is a bad thing. Whereas, from my perspective, the first thing to understand is that it is just our wealth ... [held] in the non-government sector.

"The last time I heard ... private sector wealth was a good thing."

They are familiar words, combined in an unusual order to create a totally alien meaning.

That is because Prof Mitchell is one of the leading international proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT); a framework that turns conventional economic thinking on its head.

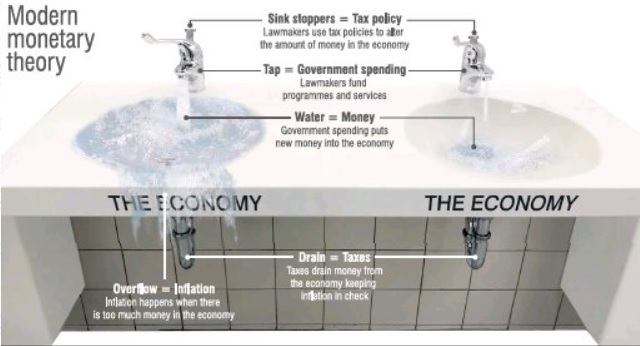

MMT says governments that issue their own currency, such as the New Zealand dollar, can spend freely because they can always create more money to pay off debts that are in their currency.

Most people do not believe that is possible. It is because we have been trained to think of the Government as identical to a household, Prof Mitchell explains.

The crucial and enormous difference, Prof Mitchell says, is that households are currency users who have to earn money to pay debt, whereas the government is the currency issuer who creates money.

That is where the rugby scoreboard analogy comes in. The Government, like a digital scoreboard, can never run out of numbers, that is, currency.

It is a bit of a head-spinner.

But once the key concept is grasped, other important implications fall out.

Government deficits, for instance, are not a problem, says Prof Stephanie Kelton, another leading MMT economist, who is a former chief economist to the United States Senate Budget Committee.

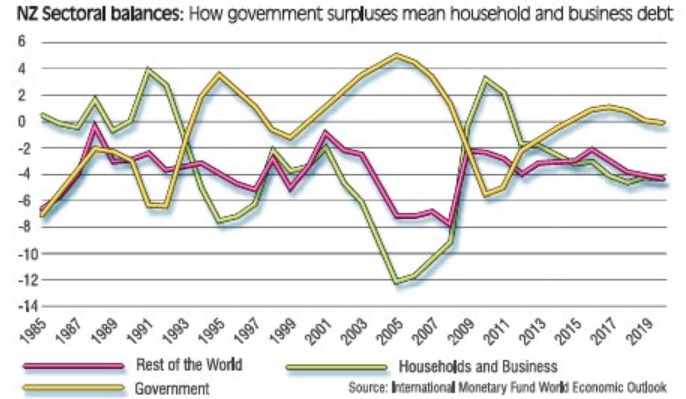

A budget deficit represents government spending that has put money in to the private sector; into households and business. But a government surplus always means greater debt for households and businesses.

That pattern is "very striking" for New Zealand, Prof Mitchell says.

"The push into fiscal surplus has forced the private domestic sector into increased deficits and indebtedness."

MMT also teaches that government spending can grow the economy to its full capacity, eliminating unemployment, adding wealth to individuals and enterprise and funding programmes, such as free healthcare and education.

It is no surprise that traditional economists take issue with MMT.

Earlier this week, I asked the finance minister why the Government was borrowing the response package money rather than just issuing it.

Robertson’s response included typical criticisms of MMT approaches.

"Printing money to fund government expenditure effectively dilutes the value of money, diminishes its purchasing power and leads to high and variable inflation," Robertson said.

"There are a number of examples of this in history, for example, Germany in the 1930s, Venezuela, Argentina and Zimbabwe."

Prof Mitchell says that is a misunderstanding of history and of economics.

In Germany, after World War 1, the Allies insisted on punishing reparation payments, which the country’s shattered economy could not afford, causing hyperinflation, he says.

“Of course, if you keep spending and you can’t produce goods to meet that spending you’ll get inflation, and if you keep spending on top of that you’ll get hyperinflation,” Mitchell says.

It is the lack of goods, labour or capacity that causes inflation, he argues.

To show that government spending does not have to cause inflation, he gives examples from Japan and the United States. Japan has a Government debt close to 240% of GDP and has an almost zero inflation rate. In the United States during the global financial crisis, the inflation rate was also close to nil, despite the Federal Reserve pumping a trillion dollars into the banking sector.

MMT proponents argue inflation can be controlled by spending less or using taxes to siphon money from the economy.

Those in the mainstream who understand the economy have occasionally, perhaps inadvertently, lifted the veil, MMT advocates say.

Prof Kelton in her January speech gave the example of Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, being asked in 2005 whether he thought government spending on retirement incomes was a problem.

Greenspan said: "There is nothing to prevent the federal government from creating as much money as it wants and paying it to somebody".

Prof Mitchell mentions Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson, who describes the belief that governments need to balance their books as "a myth".

Mitchell paraphrases Samuelson as saying: "If the rest of the population knew what we knew, and knew there was no real financial constraint on government spending, then they would put too much pressure on politicians to build good hospitals and fund education."

The pretence is maintained, Prof Mitchell says, because some people do not know better, some think it is a necessary charade to restrain government spending and others use it to further their ideological agendas.

"When a nation goes to war, nobody asks where the money is coming from," Mitchell says.

"And during the global financial crisis, nobody asked when they were baling out the banks where the money was coming from.

"But when they want to hand out a few pennies to the unemployed or to disadvantaged communities then there’s all hell to pay.

"All this hysteria about debt is just that; it’s just hysteria."

Comments

Delusional. What Mitchel is proposing is irresponsible. Printing more money to pay off government debt hurts us, the people. Germany printed money post-WWI and what happened? The devaluation of the Mark. Remember the pictures of people pushing wheelbarrows full of marks into supermarkets to buy bread? Yes the government can print until the cows come home but the value of the New Zealand dollar only goes down. It will take more New Zealand dollars to buy imports. Since New Zealand is a predominately importing country that means the price we the people pay for goods goes up. But we will get less for the limited things we manufacture here and export. If we have less tourist and less people working, the goverment makes less revenue. Printing more money is not the answer to this mess. The goverment needs to change the direction of the country and stop embracing globalism. Put the future of the country back in our hands. Start manufacturing things here for the domestic market and focus more on domestic issues. Globalism caused the problems. Nationalism and a domestic focus is the cure!

Sounds like the old Soviet printing press. The downside is it leads to shortages as no point in working if you can just print money. Then you need a military police to coerce people, so is a slippery slope. Good to read that Grant Robertson isn't interested.

Did you read the article before writing your co,ment?

Did you proof read your "co,ment" before you posted it?.

highlights that we are all slaves to this thing called money,

physically valueless, printable by few,

yet we get up 5-6 days a week to chase the stuff, so we can give it to someone else !

Where does Bruce Munro dig up these loony tunes from ? First it's Prof Patman now these MMT advocates. This is exactly how Venezuela and Argentina fell from first nation to basket case status !!!

Some of it is correct. When Cullen held the purse strings, I couldn't balance my budget because he was so focused on balancing his, via his tax take. That is why NZ was in recession before the GFC hit the world and 50,000 kiwis a year were heading off to Oz. I was one of them. It was the Clarke government that encouraged me to go.

Now I'm back I'm worried for the nation because one thing Labour governments know how to do, is spend money that is not theirs.

That leads to the second truth in this article.

"government debt .... is just our wealth ... [held] in the non-government sector."

Private wealth around the world has just taken a massive hit. NZ will be no exception. Increased govt debt against this decreased wealth makes us all the poorer. This debt is being poured into a black hole that produces nothing of value, just consumption. We would all be much better off tightening our belts and working towards making things of value, than spending more of our diminishing wealth.

Private sector wealth includes Public money.

You're quick to tar academic and knowledgeable with the epithet 'loony'. Calm down.

This is voodoo economics — the socialist analogue to the Laffer Curve — that rests on the fatal conceit that government expenditure is always good and efficient. But the truth is that, regardless of how you want to spin it, running large budget deficits eventually ends in disaster. One doesn't need to resort to extreme hyper-inflation cases — just look at 1990s Sweden and Finland. Ignoring such cases is economics denial. Meanwhile, citing Japan and the US is disingenuous to say the least — almost all of Japan's public debt is held by Japanese citizens (and it hasn't done much for the Japanese economy over the last 20 years anyway) while the US dollar is the international vehicle currency which operates to a completely different set of rules. NZ trying to emulate either of them would be a recipe for economic suicide.

I'm not convinced. Inflation is real and the principles behind it are real.

This just sounds like the next label for the next theft from the public purse, that the majority pay into, to the wealthy at the top who couldn't give a hoot for the generations who have to pay it back.

MMT is insane: it perpetuates the debtor's prison that we are all in, and will make an economic recovery much more difficult than it would be otherwise, for all the reasons that other commenters have already mentioned.

"Suckers think that you cure greed with money, addiction with substances, expert problems with experts, banking with bankers, economics with economists, and debt crises with debt spending.”

― Nassim Nicholas Taleb