The structural split of the old Telecom into Telecom and Chorus has understandably left a few investors scratching their heads.

When Telecom reported its financial results last week, investors reacted by pushing the price down by 9%. When Chorus reported on Monday, the share price rose 9%.

Telecom did, by necessity, produce a complicated set of accounts for the year ended June, taking into account seven months of Chorus and five months without the now-listed infrastructure company.

Gen-i chief executive Chris Quin fronted the Telecom results presentation as acting chief executive after the departure of former chief executive Paul Reynolds.

New chief executive Simon Moutter was present but kept his comments to his plans for the future of the retail company, something he will release early next year after his consultation with customers, clients and staff throughout the country.

Back at Gen-i, Mr Quin told the Otago Daily Times Gen-i did not own the "bottleneck" access network asset. In Otago, Chorus was the operator of the network with no retail customers.

When Gen-i wanted to provide services to its customers in the South, it bought the access from Chorus.

"We are more about being a service provider, buying components and turning them into a working network. It is a different focus, a cultural change."

Gen-i was gearing up for a busy period ahead.

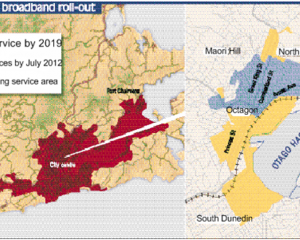

By the end of March, it was estimated that between 5% and 7% of New Zealand homes would have fibre passing them in their street.

About that time, Telecom would release its mass-market fibre products, Mr Quin said.

He expected several hundred thousand homes to have ultrafast broadband (UFB) fibre going past their doors.

Gen-i has 4200 fibre-connected commercial customers.

Several large customers were 100% fibre because of the importance of internet speed for them.

Asked why it was taking so long to release a mass-market fibre product, Mr Quin said it took time to get the right products and the right infrastructure.

"That's why we are spending $20 million building that product."

Mr Quin quoted a recent article which said a Gen-i competitor had spent nine hours with five technicians hooking up one home for UFB.

"We can't do that. We need to be much swifter than that."

While DSL provided broadband speeds of 10 megabits per second (Mbps), UFB offered 100Mbps but several things were needed before a customer could expect that sort of top speed.

To get 100Mpbs, a house had to be wired correctly.

"You are only as strong as your weakest link and if the home is not wired correctly, you won't get optimal performance."

Second, some websites would not download at the peak performance and third, a debate needed to be held on who needed speeds of more than 10Mbps or 20Mbps, he said.

Gen-i had to decide what would create demand. You could not get Sky TV through UFB, that needed a satellite.

TV-on-demand could get a speed boost through UFB, but price was an issue for homeowners who faced paying $90 or $100 a month for UFB or buying food.

"We will bring together a few things people want to enjoy at home and deliver it in an easy-to-afford package."

It was an easier decision for businesses wanting mobility, collaboration and more speed for the same money, Mr Quin said.

Businesses were moving quickly to video conferencing to conduct business around the country.

Websites often used video presentations to demonstrate products to potential customers and remote locations could be better served by companies installing video booths to allow immediate interaction with customers rather than the customer travelling to business, he said.

Mobility was becoming increasingly important but fast mobile data downloading relied on cellular network towers being connected to a fibre background. Cellular networks were not tower-to-tower but tower-to-fibre.

Collaboration meant people being able to use the same software, such as Sharepoint, to work on the same project at the same time.

That also required UFB speeds, Mr Quin said.