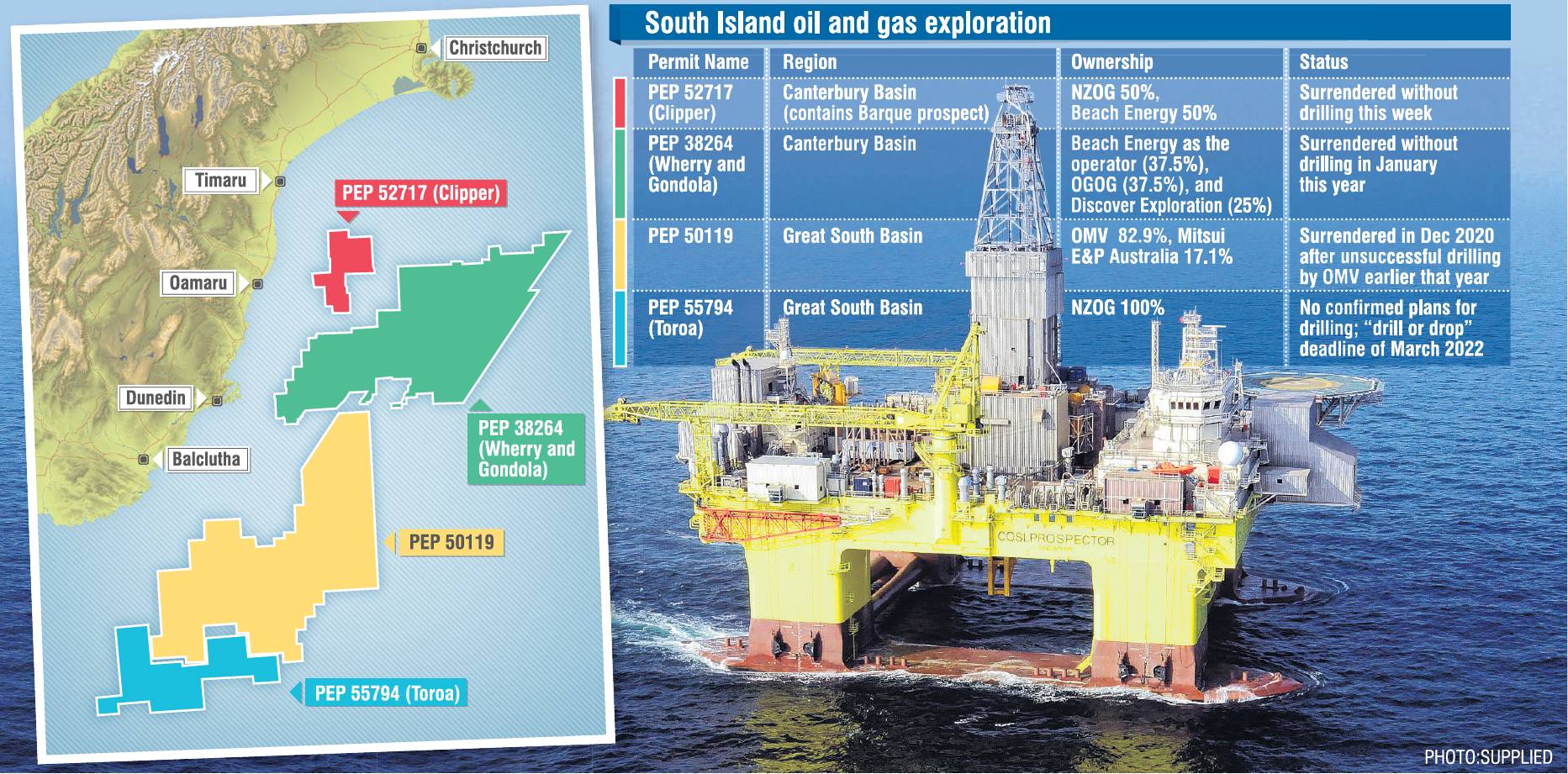

A drill or drop deadline for the last active exploration permit in the South expires in March 2022.

New Zealand Oil and Gas (NZOG) chief executive Andrew Jefferies is not optimistic about the future of the Toroa permit in the Great South Basin, which the company is likely to surrender.

"I very much doubt that the folks of Southland will see a rig over the horizon in the current regulatory settings," Mr Jefferies said.

NZOG and partner Beach Energy announced this week they would relinquish the Clipper permit in the Canterbury Basin.

In the South, that leaves only Toroa, the final active permit out of four blocks in the Great South Basin and the Canterbury Basin.

Clipper would not be the last acreage to suffer the same fate, Mr Jefferies said.

In 2018, the Government stopped issuing new exploration permits for offshore oil and gas fields, to support its commitment to action on climate change.

Twenty-three active petroleum exploration permits remained in New Zealand, an MBIE spokesman said.

A permit remained active until a surrender application had been approved.

NZ Petroleum and Minerals was assessing six applications to surrender a permit — five fully and one partially.

Mr Jefferies said the Clipper joint venture had spent about $20million and Toroa $16million on 3-D seismic acquisition in each block.

NZOG was working hard to try to find a way forward, he said.

"But it’s not looking great."

Mr Jefferies cited a much-debated economic impact assessment which found the Barque prospect, in the Clipper block, would have earned the Crown about $32billion in royalties and taxes over 25 years.

GDP would have increased by about $7billion and about 5700 construction jobs would have been created for the first five years, followed by about 2000 highly paid industrial operational jobs.

"All you need to do is look at Taranaki and see what happened when Maui was discovered and the downstream gas industry took off there."

Toroa’s fate was likely to be determined by the same confluence of events that had led NZOG to surrender Clipper, Mr Jefferies said.

They included:

■ Adverse regulatory settings for offshore exploration.

■ The dry hole at OMV’s Tawhaki permit.

■ The recent announcement terminating Wherry-1 drilling.

■ The effects of Covid-19 on drill rig costs and availability.

Those factors had formed a perfect storm for Clipper, making the task of finding suitable partners in the required timeline impossible, he said.

Many rigs had been scrapped because of low prices and lack of exploration activity.

"It’s not an easy world to get funding in and, therefore, it is very difficult to find partners to come and join in the acreage," Mr Jefferies said.

"We tend to drill as a consortium simply to spread the risk in these frontier areas.

"It is definitely a frontier area down south."

NZOG took over 100% of the Toroa permit when Woodside Energy had relinquished its 70% stake in a joint venture in 2018.

"I am loath to relinquish blocks while there is any hope," Mr Jefferies said.

Toroa was next door to the Great South Basin block that OMV drilled in partnership with Mitsui E&P Australia.

That block was found to be dry and the consortium applied to surrender it in December.

In January, the Caravelle consortium applied to surrender the Wherry prospect in the Canterbury Basin.

"Our hope was really that the Caravelle consortium would have drilled the Wherry prospect and that would have addressed some of the risks that we saw at Clipper," he said.

"If you have a discovery next door it also helps finding partners.

"That didn’t come to pass."

But the elements that made offshore frontier New Zealand attractive remained, Mr Jefferies said.

"We’ve got the eighth-largest continent in the world, it just happens to be buried under water.

"We’ve got the producing Taranaki Basin.

"All of the other basins that have been drilled have demonstrated oil and gas systems in the South but also in the east coast."

Mr Jefferies said New Zealand’s potential light hydrocarbon sources offered a higher return on investment with lower environmental impacts compared with heavy crude from Canada oil sands or Venezuelan bitumen where 50% of the world’s petroleum reserves resided.

"I would agree wholeheartedly with Greenpeace that we shouldn’t be burning half of the discovered reserves in the world."

The energy return on investment from heavy reserves required burning one barrel of oil to produce three barrels, he said.

By comparison, the ratio for New Zealand’s light hydrocarbon resources was one barrel of energy expended for 60 barrels produced.

Exploration would remain necessary as light-hydrocarbon gas continued to be consumed for decades during the transition towards cleaner energy, he said.

"But under the current regulatory settings, I can’t see a lot of people lining up to drill frontier New Zealand.

"The money will go somewhere else."