Mohua are also accomplished vocalists, and they were dubbed the bush canary by European settlers. The clear-noted song of the male is just one aspect. The foraging flocks keep in touch with a constant conversational chatter, buzzing and whistling.

Flocks of 40 or more mohua were once common in the bush around Dunedin, but disappeared 150 years ago, likely as a result of predation by rats and stoats and, possibly, the clearance of much of our mature native forest. Today if you see a small yellow bird near the city it is almost certainly a species introduced from Europe, the yellowhammer, a heavy-billed seed-eater often abundant on farmland.

To see living mohua now, you must travel further afield, in Otago to the Catlins, the Blue Mountains or the Dart Valley, where they are restricted to tawai/beech forest. Perhaps the easiest place to spot them, however, is on predator-free Ulva Island, off Rakiura/Stewart Island, where they have been introduced.

On Ulva you have a glimpse of Aotearoa as it was 150 years ago. Ceaselessly active mohua hunt for insects and other invertebrates, producing showers of leaf litter as they investigate the nooks and crannies of the forest canopy. Occasionally, they come down to eye level or even the ground.

These mohua flocks are accompanied by other bush birds that feed on the insects the mohua have disturbed: both red-crowned and yellow-crowned kākāriki, tītipounamu/rifleman, pīpipi/brown creeper, pīwakawaka/fantail, miromiro/tomtit, riroriro/grey warbler and tīeke/saddleback. Such mixed feeding flocks were once found throughout the country.

It is much easier to find pīpipi in and around Dunedin: they can be seen in the Town Belt, at Whare Flat, at the top of Mount Cargill, in Orokonui Ecosanctuary and even, on occasion, in Dunedin Botanic Garden. Like mohua, they hunt their insect prey in noisy flocks high up in the forest canopy. They are curious birds, too, sometimes coming close to investigate artificial squeaking noises.

Pīpipi have survived the onslaught of mammalian pests better than mohua, almost certainly because of their different nesting behaviour. Mohua are hole nesters, making them vulnerable to rat predation, whereas pīpipi make their own cup-like nests, hidden among dense foliage or tangled vines.

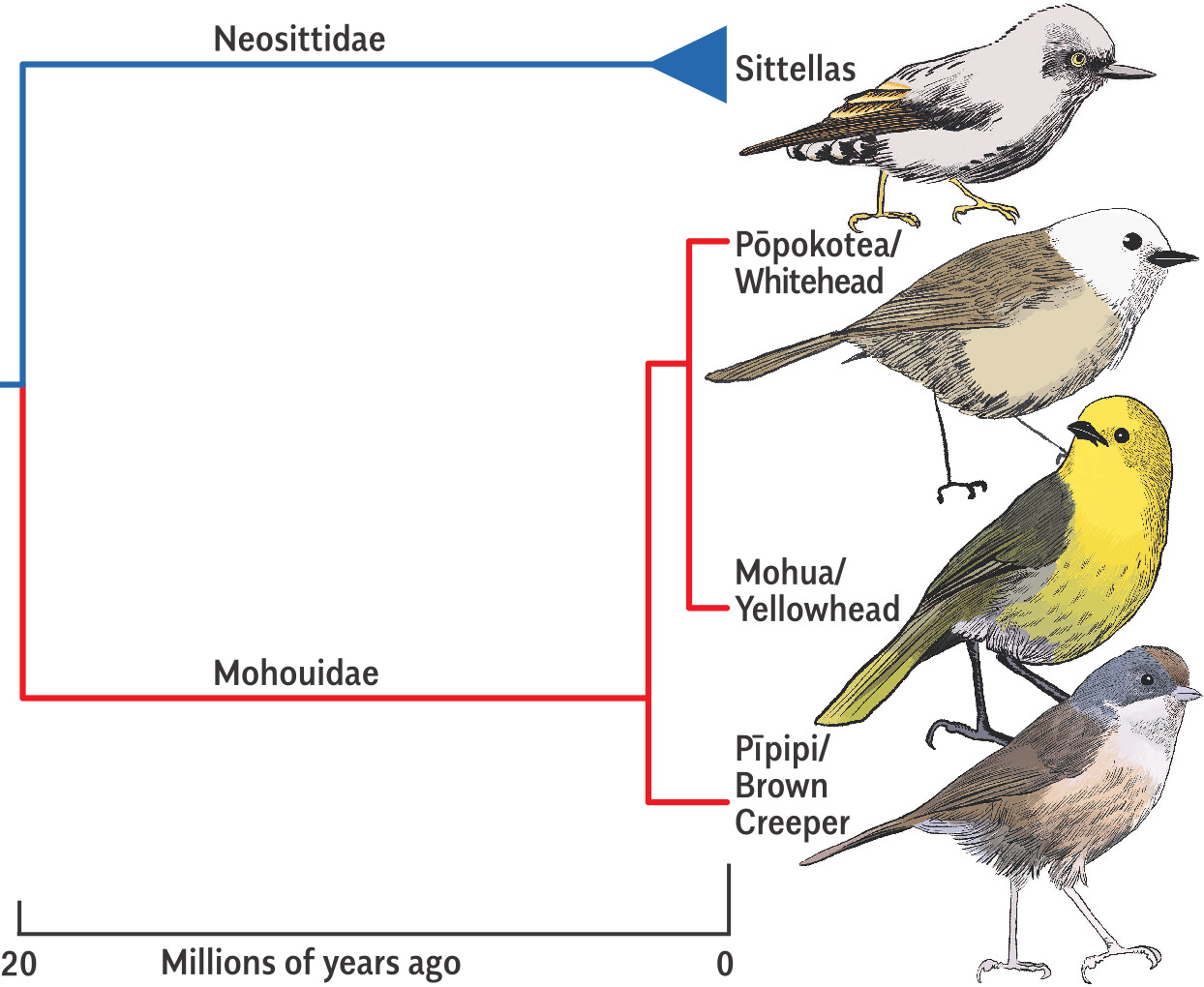

Scientists have been slow to recognise just how evolutionarily distant mohua and its relatives are from other birds. Until recently, they had been classified with some Australian birds called whistlers, but molecular genetics has shown these two groups are not even close.

Indeed, the three New Zealand species are now classified in their own endemic family (Mohouidae), which evolved about 20 million years ago (see diagram). Mohua and pōpokotea are sister species, with pīpipi a little more distantly related. Their closest relatives are sittellas from Australia and New Guinea, which also forage for insects hiding on tree trunks and branches.

So, if you are off on a bush walk this summer, listen for a flock of chattering birds. Quite different from the lisping whistle of silvereyes, this sound can only be heard in Aotearoa. Then look up and, with luck you’ll be rewarded with a glimpse of what the bush was once like and, once we get mammalian predators under control, what it may be like again!

Hamish G. Spencer is Sesquicentennial Distinguished Professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Otago.