It turns out, however, that I can get a glimpse of some equally special Aotearoa New Zealand birdlife right here in Dunedin, something living that also dates from ancient times. The rifleman or titipounamu lives in the Town Belt, especially in stands of kanuka near Ross Creek Reservoir, and in Orokonui Ecosanctuary. I once saw a pair near the Pyramids on Otago Peninsula.

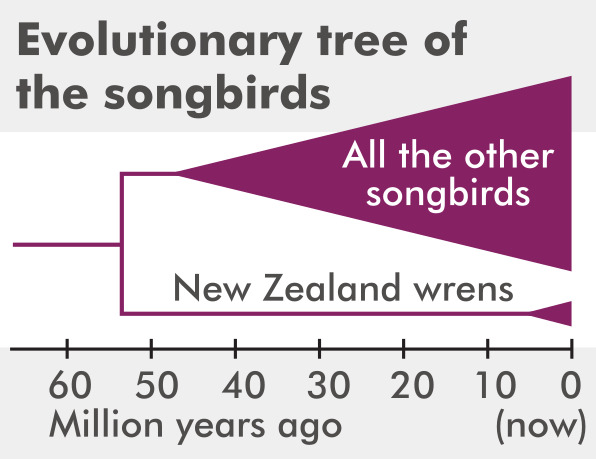

In the family tree of birds, this group is all that is left of a branch next to the branch that leads to all the other songbirds (also called passerines), such as sparrows, robins, crows, honeyeaters, finches and thrushes. In short, the New Zealand wrens (not to be confused with ‘‘proper’’ wrens from elsewhere in the world) are as distinct from any other living songbird as the moa are from the tinamou.

Not so long ago, there were more living New Zealand wren species. The last bush wren or matuhituhi died in 1972 on Kaimohu Island, off Rakiura, Stewart Island. A small number of birds had been translocated there after their last natural population on Taukihepa was exterminated by rats in 1965. Sadly, this conservation effort failed.

Even more poignant is the story of Lyall’s wren. This species was one of the few songbirds known to be flightless. The last relict population, on Stephens Island, Takapourewa, was discovered in 1894 (hence the alternative name, Stephens Island wren). Feral cats, probably introduced by lighthouse keepers, quickly hunted the population to extinction, almost before anyone realised just how special these birds were.

To go back further in the past, we need to look at ancient bone deposits, often from caves where they were taken by owls and other predatory birds. If we do so, we can see that at least three other New Zealand wren species survived until after the arrival of Maori.

Hence the species living today are just a pair from the seven of 1000 years ago.

So next time you are wandering around the bush near Dunedin, look out for New Zealand’s smallest bird species, the rifleman. They are usually in pairs or small family groups, foraging high up on the trunks and branches of trees. The males have dark green backs; the females are brown and pale yellow.

Reflecting their evolutionary distinctiveness, they look really different from other songbirds, with almost no tail.

Listen hard for their constant contact calls, so amazingly high-pitched that not everyone can hear them. And then luxuriate in knowing that this taonga is as special as a moa!

- Hamish G. Spencer is Sesquicentennial Distinguished Professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Otago.