It’s a diverse chorus of voices that makes our sound of summer.

When, 60 years ago, Nat King Cole crooned about those lazy-hazy-crazy days of summer, he had clearly never been to Aotearoa New Zealand. If he had, he surely would have mentioned, as background music to the consumption of ‘‘soda and pretzels and beer’’, the sound of our summer - the incessant and occasionally deafening singing of cicadas.

Indeed, I can hear several cicadas singing now. They are all males, doing their best to attract females and each species has a distinctive song. Female cicadas do not sing, but they do respond to the males’ song by clicking their wings. These fascinating insects do not have long to find a mate: adults live for only two or three weeks.

Actually, ‘‘song’’ is possibly the wrong word. Male cicadas chirp and buzz using ribbed membranes called tymbals, one on each side of the abdomen. By rapidly contracting and relaxing the abdominal muscles, the tymbals pop in and out, like a piece of hard plastic being flexed (but far, far faster). Clicking noises may be added by clapping their wings against their abdomen. The song is amplified both by the males’ largely hollow abdomens acting like soundboxes, as well as by structures called opercula on the underside of the abdomen. The end result is an incredibly loud racket of up to 120 decibels (more than a pneumatic drill, at up to 100db, less than a jet taking off, at 140db). A cicada too near your ear could actually damage your hearing!

So, all that noise is just to allow males to find a mate. After mating, a female cicada can lay several hundred eggs, using a special needle-like structure on her abdomen called an ovipositor. She inserts her ovipositor into a branch and deposits her fertilised eggs, which hatch as wingless nymphs several months later. These nymphs fall from the tree or shrub and dig themselves underground, where they eat the roots of plants, growing slowly and moulting several times. Two or three years later, they return to the surface, before moulting for the final time and emerging as winged adults. The nymphs of some North American species spend an amazing 17 years underground!

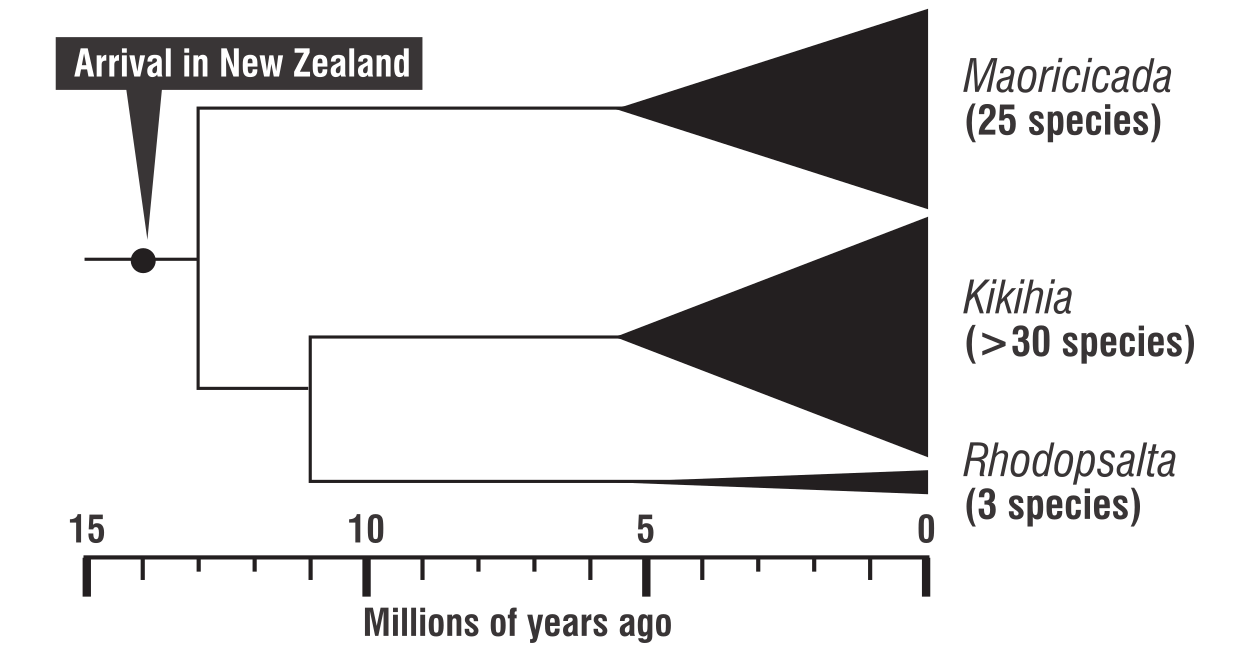

Aotearoa has more than 60 species of cicada. They fall into five groups, what scientists call genera (the plural of genus), whose evolutionary relationships have been studied extensively using genetic techniques. All of our species are descended from two ancient species that independently arrived in proto-New Zealand during the Miocene epoch, no more than 14million years ago. One of these colonising species probably originated in Australia, whereas the other came from the north, possibly New Caledonia.

These two invaders gave rise to two very different lineages. The northern lineage comprises three genera, two of which have diversified into numerous species across the country. There are now more than 30 species of kikihi cicadas (Kikihia) and about 25 of the black cicadas (Maoricicada). By contrast, the remaining genus in this lineage, the red-tailed cicadas (Rhodopsalta), has just three species, and in the second, Australian-derived lineage, there are just three species of the clapping cicadas (Amphipsalta) and one clay-bank cicada (Notopsalta).

Why some groups have speciated like crazy and others are species-poor is not clear, although New Zealand’s rapidly changing paleogeology is surely part of the reason. During the Pliocene and Pleistocene, which followed the Miocene, different cicada populations would have been isolated by glacial ice fields and newly arisen mountain ranges. This isolation might have allowed some populations to evolve into separate species, whereas other populations would have been exterminated.

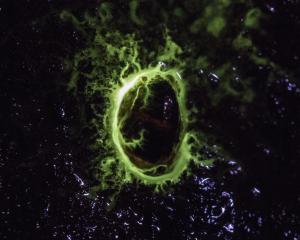

Our best-known species is a kind of clapping cicada, the chorus cicada/kihikihi wawa, stunningly patterned with green and black. Our largest and loudest species, it has a total length of 40mm. It can be found throughout the country, although it has only been recorded from Dunedin in the past 10 years.

About half the length is the subalpine cicada, a species of Kikihia, which is also common around Dunedin. One singing male landed on me when I was in our garden last weekend. It was a beautiful golden brown, rather than the usual green. Such variation in colour is widespread in our cicadas.

All our species of cicadas are endemic, living nowhere else in the world. Moreover, several species of Maoricicada live in snowy montane habitats; they seem to be the only alpine cicadas in the world. The way in which our cicadas have diversified (or not) has engaged the interests of scientists worldwide. These fascinating animals enrich our summers with their stunning colouration and instantly recognisable chirping, and are as sure a sign of summer as the clicking of jandals (which Nat King Cole didn’t mention either). For all these reasons, they truly are a national taonga!

Hamish G. Spencer is sesquicentennial distinguished professor in the department of zoology at the University of Otago.