We crept forward towards the clay bank under dripping ferns in the small piece of remnant native bush. Carefully, we manoeuvred the heavy tube we were carrying into position near a deep hole in the bank, and prised off the tube’s end cover. Nothing happened. We waited. Still nothing. So we gave the tube a gentle shake. Suddenly, the tube jerked, there was a scuttling noise, and something big ran into the hole. Our tube had become a whole lot lighter.

I had just had the amazing privilege of helping to re-establish a population of tuatara at Te Kuri o Paoa, Young Nick’s Head, south of Gisborne. As a guest of Ngai Tamanuhiri, I was inside a predator-proof fenced sanctuary, into which, over several years, various taonga species have been released. Now, weka, giant weta, tuatara, korora (blue penguins) and other animals that had previously become extinct in the area can be found in the regenerating bush.

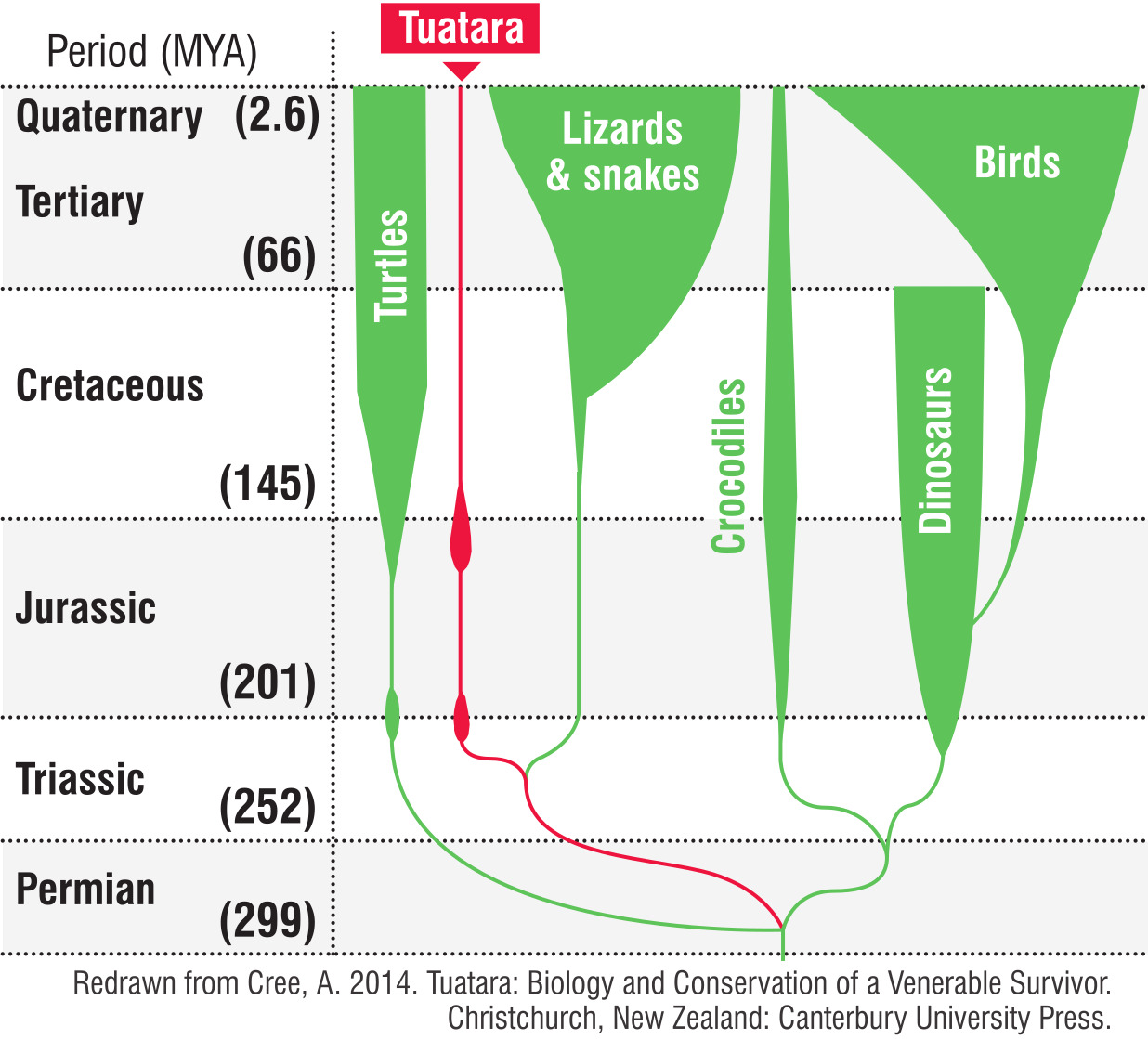

From a scientific viewpoint, tuatara are one of the jewels in the crown of our indigenous fauna. For a start, like so many other native organisms, tuatara are found nowhere else in the world: they are endemic to Aotearoa New Zealand. Once upon a time, they were called "living fossils", but this description is now considered inaccurate. The label seems to imply that tuatara stopped evolving and are the same as they were millions of years ago, which isn’t true. Known fossils of Sphenodon, the genus of tuatara, date back to no more than about 100,000 years.

The East Polynesians who first settled this country recognised the tuatara as special, and its Maori name references the distinctive row of spines down its back. Victorian naturalists classified tuatara separately from lizards due to unique aspects of its skeleton, notably the skull. More recently, physiologists have discovered that sex in tuatara is determined in a very different way compared to humans and other mammals.

Unlike mammals in which males and females have different sex chromosomes, tuatara display so-called "temperature-dependent sex determination" (TSD). Many lizards and turtles also use TSD, with eggs reared at lower temperatures producing males and those at higher temperatures, females. However, tuatara reverse this pattern. Eggs incubated at a lower temperature (below approximately 21.2degC) become females, those incubated at higher temperatures (above approximately 22.2degC) develop as males, with intermediate temperatures producing both sexes.

TSD in the time of climate change presents a long-term dilemma for tuatara. Will some places become too hot for eggs to ever give rise to females? Such a scenario sounds quite plausible on small rocky islets off the Northland coast, from which there is no escape from the heat. Without intervention by conservation managers, local extinction would inevitably follow. On larger, less exposed, islands though, reproductive females may be able to compensate and lay some of their eggs in cooler places, perhaps further down in the soil or in shadier forest.

However, in the short-term, introductions of tuatara to fenced sanctuaries and predator-free islands continue, supported by iwi as kaitiaki. Many of these efforts have been so effective that the Department of Conservation no longer considers our special endemic reptile to be "threatened". Rather, the tuatara is classified as "at risk", relying on relict/island/sanctuary populations, reflecting its disappearance from the mainland after the arrival of people and mammalian predators less than 1000 years ago. Wellington’s Zealandia is a great example of a successful reintroduction. The last time I visited this urban protected area, tuatara were everywhere, wandering around unconcerned on the paths and tracks.

Another place tuatara have been reintroduced is Dunedin’s Orokonui Ecosanctuary. This preserve, being further south and hence generally cooler, may become crucial for tuatara conservation. Surely, some tuatara eggs in Orokonui must develop as females, even as our climate warms. So next time you visit Orokonui, take a look in the small enclosure near the entrance gate. You may spot a tuatara sunning itself in the afternoon light. And if you are lucky enough to see one of the free-roaming individuals elsewhere in the sanctuary, consider that its destiny might be as the ancestor of tuatara for centuries to come.

Hamish G. Spencer is Sesquicentennial Distinguished Professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Otago. Each week in this column, writers addresses issues of sustainability.