Chris Adams’ contribution to the geochronology of New Zealand and Antarctica is acknowledged to be unrivalled but his work as an artist is lesser known. Rebecca Fox talks to Adams about the first survey show of his mezzotints.

Standing at the back of a boat watching the sun come up over the snow-capped subantarctic Mt Honey is a magic moment Chris Adams will never forget.

He had just woken up as the boat was about to leave the Campbell Islands.

‘‘It only lasted literally, quite literally, only about 30 seconds. The clouds moved and that’s it. From this point on the Campbell Islands will become pretty inhospitable.’’

That vision inspired his mezzotint First light, first snow, Mt Honey, a good example of how his work as a geochronologist has inspired his artwork.

Along the way he rediscovered his love of art at night classes, a popular activity for many in the 1980s. Living in Wellington by then, the Englishman discovered the work of printmaker John Drawbridge.

‘‘I was impressed by his style. He’s a very interesting man, quite a famous New Zealand artist. So I was quite flattered when he offered to give us all mostly weekend classes in printmaking.’’

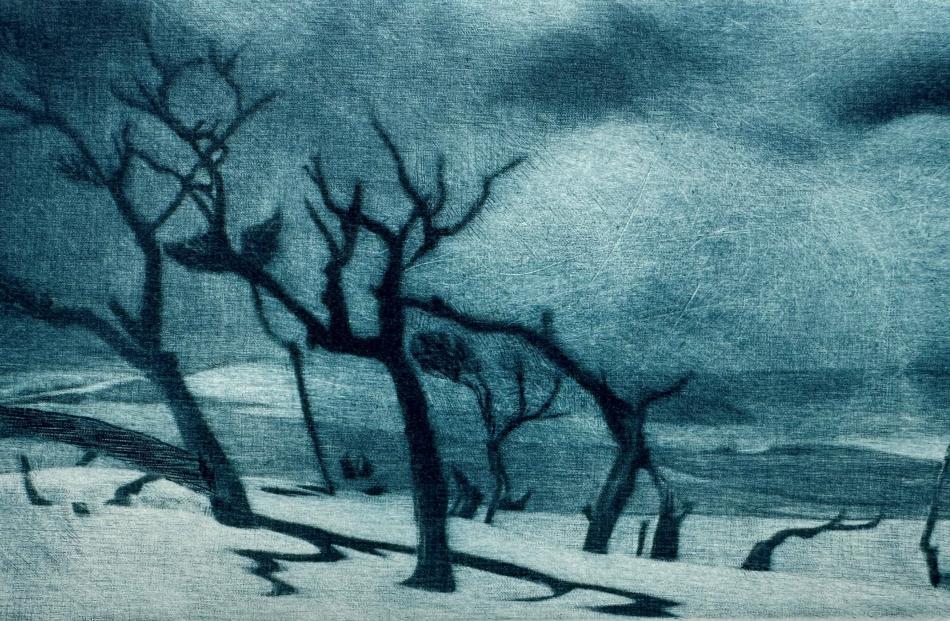

What captured Adams’ attention was Drawbridge’s mezzotint style. Creating mezzotints involves scraping and polishing an engraved copper or steel plate to make a print.

‘‘It is a style which relies not so much on lines drawn on a surface, in other words, drawing. It more involves the exploration of tone. In other words, arranging the paper, arranging the image as a group of tones.’’

Drawbridge thought it was a style that could be very therapeutic for Adams.

‘‘He had watched me at art classes and he said that I was obsessed by lines. So he carefully took the pencil away and introduced me to that style.’’

Up until the 1850s it was the only good way of producing high-quality illustrations but when photography came in the practice disappeared completely.

But as an art form it had its supporters, such as Drawbridge. Over the next few years Adams worked with Drawbridge at Inverlochy Art School learning to produce mezzotints.

‘‘The science, I’ve always been passionate about it, but it doesn’t overwhelm me. And I’m always well aware to make sure that I’ve got lots of time for the printmaking.’’

The main problem has always been having access to a printmaker’s studio, but Inverlochy gave him that access, so he spent many a weekend afternoon working on his prints there.

Creating mezzotints is a time-consuming practice. For Adams it starts out with photographs. He then makes sketches to get the tonal contrast right.

‘‘I really have to judge how the tone will be transferred on to the copper plate. This is very difficult because very often it’s hard to judge the depth of tones from different colours.’’

Adams describes the process as challenging and laborious but he does it because he loves it.

‘‘Mezzotint engraving is not for the spontaneous, edgy, funky artist. It’s a slow, slow process. Physically preparing the plate takes a day and then developing the image goes through at least 10 states, which can take up to five or six days. In fact, most mezzotint printmakers would say that a print takes a month from start to finish. So it’s a very slow process and it’s not easy to correct mistakes. It’s a pretty unforgiving technique.’’

However, it appeals to the scientist in him.

‘‘Let’s face it, scientists have to proceed according to rules and scientists are not allowed to make mistakes. And if they make mistakes, they have to be corrected.’’

BY the late 1990s he had enough work for an exhibition, taking inspiration for the works from poet Lauris Edmond’s (1924-2000) sequence of poems Wellington Letter (1980). The exhibition The Stars Take Only Their Dark Road was opened by Drawbridge and his sculptor wife Tanya Ashken.

‘‘I enjoyed going through her poems and producing mezzotints that would accompany her poems.’’

Then a few years later, he did a similar exhibition with a friend who had unpublished poetry, Michelle Burgess.

‘‘I’ve always found the same wonderful magic in poets. You know, you read a poem and just one line says it all. Just says it all. This is why I enjoyed, for example, Lauris Edmond’s poetry. And I found that she had this ability to capture the essence of a human emotion or a human condition in just a few words. Literally, just a few words, just a phrase.’’

Adams, who was born in 1942 and studied at the Universities of London and Oxford, came to New Zealand in 1969 to work at the DSIR’s Institute of Nuclear Sciences (INS) and set up a geochronology laboratory to measure the age of rocks. He spent much of his career travelling around the nation and its islands to collect samples, and also to Antarctica.

The sights he saw on these trips inspired his artwork.

‘‘As a geologist, I went down to the islands to study the rocks, but was fascinated by the beautiful fleeting landscapes, seascapes, cloudscapes, that these wilderness places provide.

‘‘I decided it was time to get into landscape, mainly because I was always aware on my travels that landscape is often boiled down to an almost instantaneous image that you see when you’re looking at a landscape. There seems to be a fleeting second when the essential landscape becomes apparent. And that’s what I’ve tried to capture in my work.’’

‘‘I had hundreds of photographs and sketches of the beautiful landscape there.’’

The works those images inspired were shown in ‘‘Fine Spells, Rain Later’’ (2017 - The Chatham Islands) at Wellington’s Solender Gallery.

He was also encouraged to create some works of Wellington.

‘‘As anybody who’s lived in Wellington knows, it’s a very fast-moving landscape. Again, a complex mixture of landscapes, seascapes and cloudscapes. And that’s what I try to capture in my work. And that exhibition was called ‘‘Spirit of Place’’, which comes from a book by Lawrence Durrell on the islands of Greece.’’

About 14 years ago, after many, many visits to Dunedin due to his work in the Antarctic and subantarctic islands, he made the decision to move to Otago Peninsula after being encouraged to do so by many of his southern friends and colleagues.

‘‘Gradually, I decided that Dunedin was a good place to live. I had social friends on the Otago Peninsula.They suggested that I buy a crib. And I eventually built a house.’’

Retired from daily work, he made sure he included a print studio in his new house and brought in his own printing press. Prior to that he was able to use friend Inge Doesberg’s studio when he was in Dunedin.

These days he is inspired by the Dunedin and Otago landscape and flowers. His flower works are mainly done for family members to mark birthdays and special occasions.

However, one, a japonica blossom, has been on show at Fe29’s Drawbridge exhibition as a tribute to the late artist’s influence on his art. It is a personal favourite of Adams and one he describes as a perfect mezzotint.

Following the Drawbridge exhibition with one of his own feels like a huge privilege, he says.

‘‘Because I feel I’m very much a disciple of John Drawbridge.’’

The survey show ‘‘Travellers in Zealandia’’ includes works from across his different shows and from his various travels.

‘‘That is not just physical travels through Zealandia’s landscape. It’s actually travels through the eyes of poets on New Zealanders, people. So these are physical travels and emotional journeys.’’

While these days his art dominates, he maintains an interest in geochronology and finishing projects he had to put on the backburner during his career.

After speaking to the Otago Daily Times, he was heading home to revise an article on his latest research project in which they have discovered some of the oldest minerals in New Zealand.

‘‘There are some sandstones in Nelson province which have minerals which are incredibly old. I mean, when I say incredibly, I mean it.

They are 3500 million years old. So they are almost, well, let’s think, they are almost eight times older than the oldest rocks in New Zealand. The oldest rocks in New Zealand are 500 million years old. But inside those rocks, there are minerals which are incredibly old, and that’s been very exciting to discover those.’’

When he is finished revising he will return to creating mezzotints for his next exhibition later this year of Otago works.

To see

‘‘Travels in Zealandia’’, Chris Adams

Fe29 St Clair

March 14 to April 28