From twilight, the anticipation mounts as Shireen Taweel watches for the first stars to emerge in the night sky.

Slowly tracking the stars’ movement through the sky using instruments — southern celestial devices — she has created herself, based on the Arabic navigation instruments she discovered in European museums, Taweel plots her next move across the South Island.

Beginning in Dunedin, at 45° south, she heads slowly northwest towards the West Coast, traversing lake and alpine terrain and the odd snowfall.

The pilgrimage is in stark contrast to her last journey across the deserts of Australia during the dry months.

"There was much more distance and a different climate. We had clear skies but dry deserts, which was really extraordinary.

"It was so fascinating that only a few months later here we are on the South Island in spring, so different stars and points of latitude, but also extraordinarily different climate and landscape and season, so all of that variation has created such a spectrum of experience."

That experience has helped the Sydney-based multidisciplinary research-led artist form her Dunedin Public Art Gallery exhibition "5364 nocturne", which refers to the nautical miles between Dunedin and the points of pilgrimage across the Australian continent, showing the relationship between the two sites.

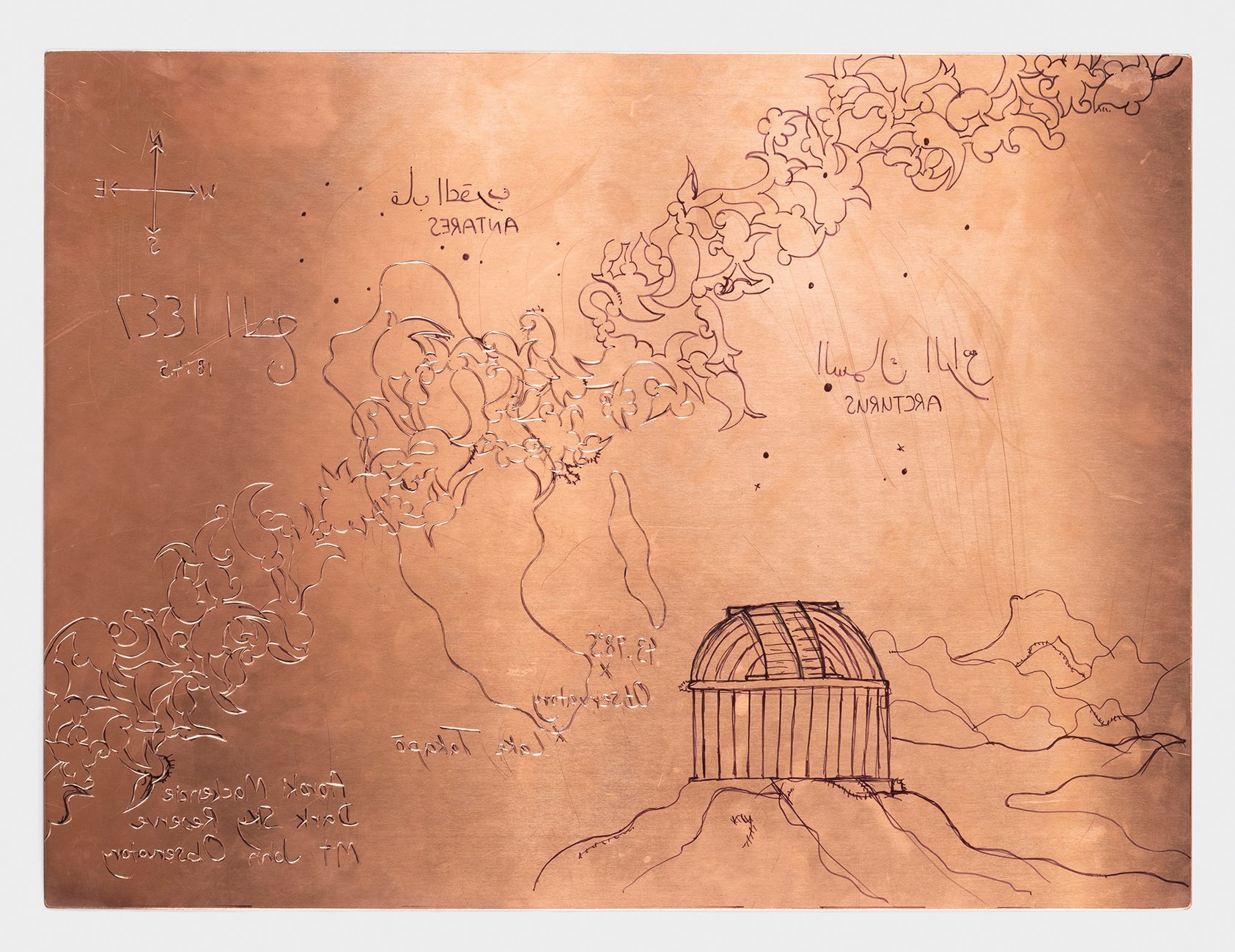

The pilgrimage from Dunedin to Tekapo and Mt Cook/Aoraki and across to the West Coast has developed into a moving image work, and her drawings and mapping of the journey have been turned into copper-engraved prints.

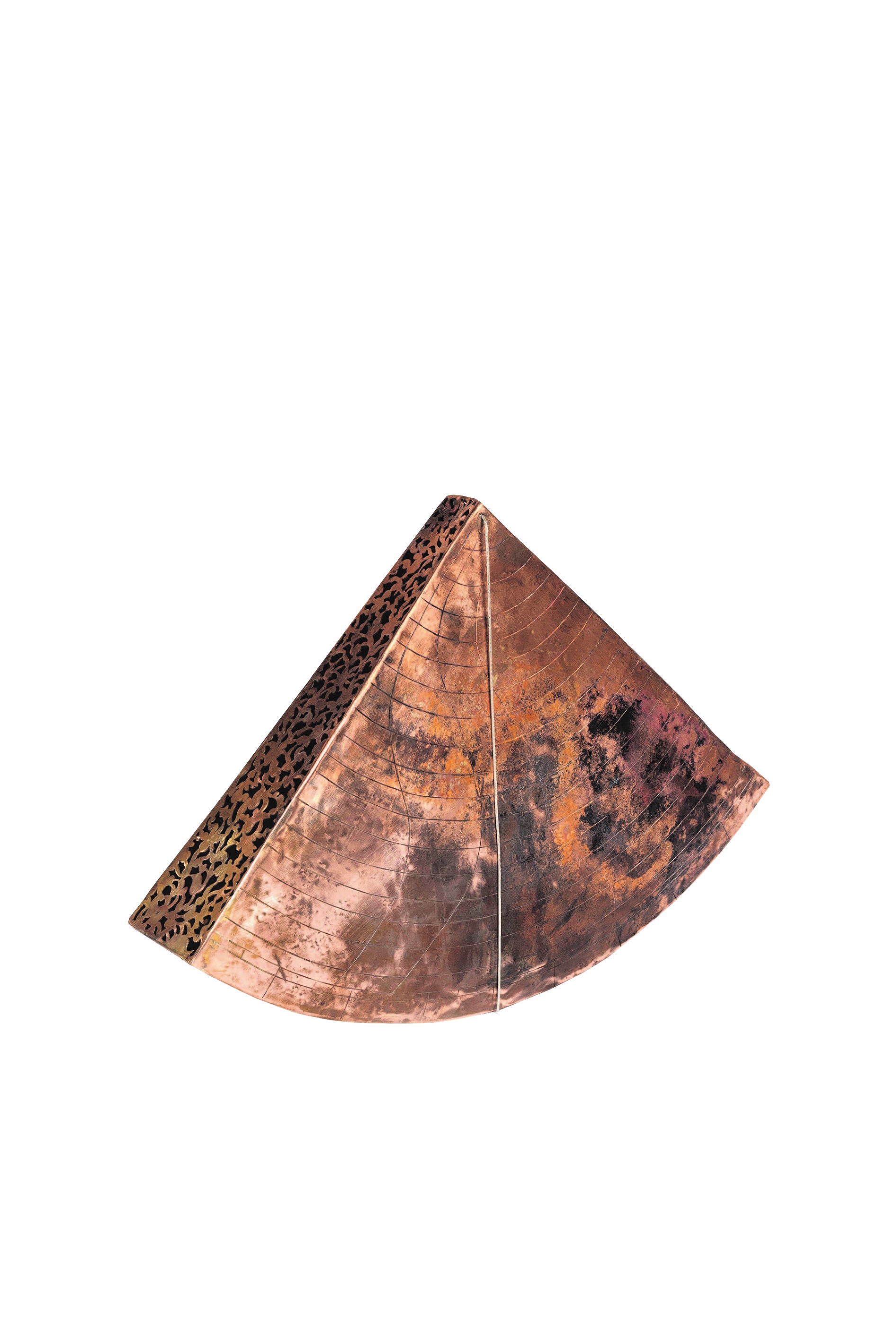

Alongside these sit the instruments she created out of copper. They are beautiful and sculptural but also have a purpose. The astrolabe and quadrant have the latitudes of both pilgrimages on them.

They are in direct contrast to the ancient instruments used in the Arab region in the ninth to 18th centuries, which were made up of northern hemisphere latitudes.

"It was really exciting — having dwelled into that research for years now — to apply it to where I exist and my environment and my cultural landscape here in the southern part of the world."

It is also extraordinary, as Taweel had no scientific background at all before she started this line of research. She had studied languages before the draw of art school became too much to ignore.

Growing up, museums and galleries were not part of her cultural landscape, so the idea of being an artist was not something she ever imagined. It was not until university she discovered she was spending more time in those institutions than anywhere else. There was also no joy in her linguistic studies any more.

"I thought, ‘I think I need to listen to this’ but I just felt like ‘I can't go to art school, I've never made art before’. I was at a real fork in the road."

So she headed overseas, doing her own pilgrimage to relatives in Lebanon, living in Turkey for six months and spending time in Egypt and Jordan, where she immersed herself in all things cultural, including visiting museums and galleries.

"Then the the desire to go to art school was so strong I couldn't not apply. I applied to go to art school and from day one was there every day."

It is something she has not regretted as it enabled her to discover copper as a material, something she felt at home with straight away, despite not being trained in jewellery or coppersmithing. She puts that down to growing up surrounded by objects, such as lamps and trays, from the Swana region in North Africa, the Arab world, Turkey and central Asia, many brought with her parents when they migrated to Australia from Lebanon.

"Because they were handmade and came from the like Arab-North African region they were really special and I think that cultural association just directed me at art school to experiment."

Beginning with hand-forming objects, Taweel then tried her hand at etching and teaching herself to use a hand-saw to create cut-outs. She learned the material was very unforgiving, demanding time and patience and a lot of trial and error. She then undertook a three-month internship in southern Turkey with master copper engravers to learn detailed mark-making.

"Over the last decade to have built up a really exciting studio, I could almost say like guild — but it's like I wouldn't dare call it that as in the master's eyes I'm still like an apprentice — but it's been great. I've built up so many different processes that I apply to my sculptures and installations and my devices that I'm always learning."

Her work Tracing Transcendence took three years to complete. The three large hand-pierced rounds of copper required her to drill thousands of tiny holes and then saw each tiny section out.

"It was a really important project because I was looking at the first mosques in remote Australia and that was a history I hadn't known about, and I was really fascinated the way those mosques developed from the cameleers who worked in the interior of the country.

"I thought this is such a wonderful history that I hope more people can know about, so I think the beauty of the cameleers’ contribution really inspired me to apply so much time and labour to realising that artwork."

It was not until she was in France and the UK working on the collections at the Paris observatory, the Arab World Institute and an Oxford science museum that she discovered the amazing navigation collections from Arab astronomy. The instruments were made from the same materials she employed in her studio using similar tools.

"They're all beautifully engraved, they're pierced, they're soldered with fine silver to join them together, so I was really blown away.

Having created her southern celestial devices she was able to plan her pilgrimages, allowing her for the first time to bring together the science knowledge she had slowly been building and learning since 2022 when she received a residency at the Sydney Observatory.

Her initial interest in celestial navigation was "purely a curiosity" as a child of migrants about how people have moved across land and sea.

At the observatory she looked into seafaring and came across navigation instruments dating from the 1700s. The mathematics involved in these instruments, and how it correlated with the science in them, interested her.

It was from this experience that she could see a bridge from the European navigational instruments to those used in the Arab world.

"I started inquiring into Arab astronomy and was really amazed by the depths of that astronomy and its contribution to mathematics."

As an artist she was also fascinated by how these mathematical, scientific instruments were developed to be functional but also had a spiritual dimension to them, as the latitudes in the instruments referred to Mecca where the Hajj is undertaken, a significant activity in the Islamic faith.

In turn, that led to her querying the cultural uses of the instruments for migration or travel such as pilgrimages.

"Coming from the Muslim community and like many communities across the Arab world of all faiths, pilgrimage is a real key element to reasons of travel or migration, and I was really fascinated by what the notion of a pilgrim travelling with this technology could look like today or in the future."

Her experience in Europe kept her questioning why the Arab world’s contribution to the science was not acknowledged in a greater way.

As an artist she was curious about bringing faith, art and culture into the the employment of the science and what that could look like today, but also in the future.

"Who can access the sky and the stars and [the] like now in our cities? Unfortunately, this is a big environmental issue, too, with light pollution, and so I thought it would be fascinating to move through the sky with navigation and employment of these sciences in my own form as a pilgrimage."

Having Arab heritage, she also found it fascinating how the sciences involved in navigation have also shaped today’s space industry and the mathematics used in computer science.

That in turn raised questions for Taweel about the future of space exploration and who gets experience space in the future.

"What [are] the reasons to experience space? And if there are cultural activities in space, what could [those] look like?"

Going back to Sydney and city life, in which the ability to see the stars is often very restricted, may be difficult after her experiences in the Mackenzie Basin, where she could see the Milky Way, magnetic clouds and galaxies too faint to see without a high degree of darkness, Taweel admits.

"It’s just phenomenal to witness this and I wonder — if we had the access to this world at night, I'm sure people would have a different sense of place and belonging. It's just extraordinary when you get to look up and realise how small you are."

TO SEE:

Shireen Taweel: "5364 nocturne", Dunedin Public Art Gallery until March 2, 2025; Artist talk: 11am, October 5, Shireen Taweel and DPAG curator Lauren Gutsell.