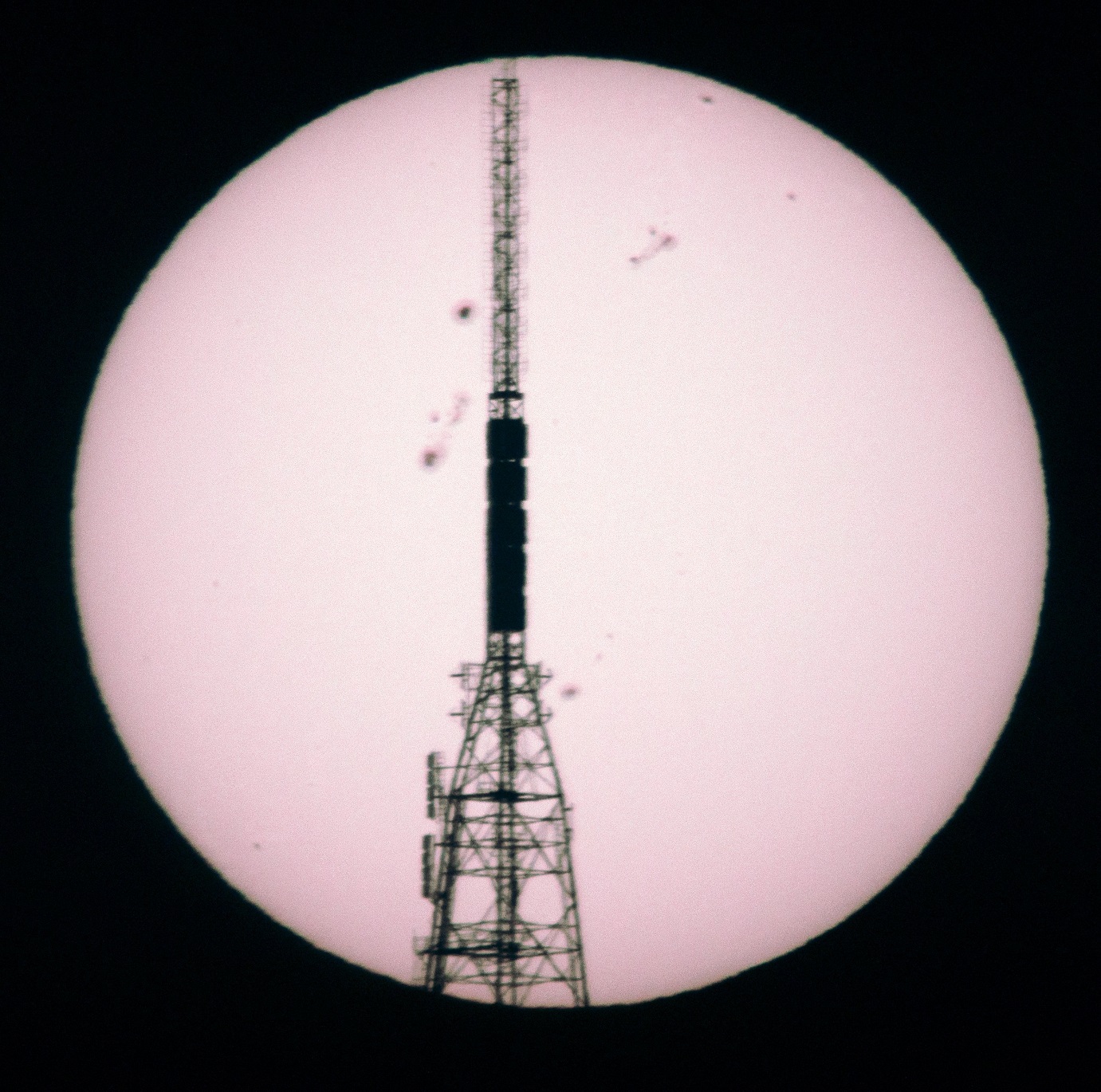

Since discovering this remarkable phenomenon in 2015, "Mount Cargill Sunset" has become a much-anticipated staple in my calendar.

Whenever possible, the Griffin whānau gather on the deck, share a few glasses of wine and enjoy the sight of our nearest star, setting behind the 105m high structure, which is 7.5km away, as the kererū flies from my Portobello home.

In my case, I always use special filters to protect my cameras and my eyes from the sun’s tremendous heat and light.

On August 21 this year, conditions were near perfect for observing the sunset.

The sky was clear and blue, and there was little wind.

I gasped in awe as I excitedly pointed my telescope at the sun.

The sun’s surface was teeming with dark sunspots, some of which appeared huge.

The number of sunspots on the sun is at a 20-year high as we approach the peak of solar activity.

When more sunspots are seen, solar activity is said to be high.

The sunspots, which are cool areas in the solar atmosphere, correspond with regions of intense magnetism on the solar surface.

They crackle with energy, which, when explosively released, sometimes throws solar material towards Earth, generating powerful geomagnetic storms upon its arrival.

Indeed, the reason we have seen lots of auroras recently is because we are close to solar maximum.

Looking back through my collection of images of Mount Cargill sunsets, I have never seen so many sunspots on the sun; this isn’t surprising as I began observing well after the last solar maximum in 2013.

As the sun, 150 million kilometres away, sinks behind the TV tower, the vista always creates a profound sense of scale.

Its enormity contrasts with the tower’s silhouette, reminding us of our place in the universe.