It’s hard to go past the old chestnut of judging a book by its cover with former health boss and political guru Richard Thomson.

A force to be reckoned with in the South over many years, he comes across as diffident and self-deprecating when The Weekend Mix catches up with him about his impending retirement from most public duties.

There’s still a streak of rebelliousness in the erstwhile political and environmental activist, who delights in pointing out he has been sacked three times by ministers of health.

In his more militant youth, he says he had a good friend who called him "the laughing Stalinist", perhaps as much in homage to his moustache as for any Machiavellian political manoeuvring.

"I think she also thought that if it was necessary to shoot a few people to achieve the goal, I may have been up to it. I have mellowed over the years."

He did play a part in rolling well-established Dunedin Central Labour MP Brian MacDonell. When his electorate was abolished in 1983, MacDonell, who had had 20 years in Parliament, was not selected the next year for the new Dunedin West seat.

Thomson says he soon realised he "didn’t have the stomach" for cut-throat politics.

Today the owner of 22 Acquisitions shops across the country is working in its small upstairs Dunedin head office.

"How about I lurk outside the front of Marbecks in Wall St," Thomson said when asked for an interview, "and we can pick up a coffee?"

"I am the bearded, bespectacled, elderly gent looking like he is lost outside the coffee shop."

Where to start? With his trials and tribulations and sackings from health boards, and the $16.9 million Michael Swann fraud case?

The many ordeals of Te Whatu Ora-Health New Zealand, the appointment of Lester Levy as commissioner, and the future of the new Dunedin hospital?

Or the night the now 68-year-old played bagpipes for glam-rock shocker Gary Glitter in a mid-1970s Dunedin concert?

Thomson was born in Invercargill, studied and trained at the University of Otago as a clinical psychologist, and then worked as a lecturer in psychological medicine at the Otago Medical School.

But there were too many environmental and political distractions to keep him there.

By the late 1970s he was one of two deputy leaders of the Values Party, trying to bring together factions warring over the leadership. And there was the fight against Robert Muldoon’s National government proposal for an aluminium smelter at Aramoana.

"I loved the teaching, but I just didn’t know whether I wanted to be seeing Mr Brown at 9 o’clock and Mrs Green at 10 o’clock for the rest of my life.

"I was involved in the campaign to stop them building an Aramoana smelter. And my mate who was the manager at Cherry Farm hospital and I were kind of asked if we were interested in running the Save Aramoana campaign on a paid basis, though ‘pay’ is a misnomer — it was just enough to keep you alive.

"I thought it was the most ludicrous thing to look to build. It was like a ‘cargo cult’ mentality in Dunedin in those days. I was able to do a bit of private practice on the side just to pay the rent. And we ran that campaign from the designated ‘environment centre’."

In 1982 the National government canned the smelter proposal and the land at Aramoana was finally zoned as reserve.

"At that point, we’d started Acquisitions. It was an accident, like most of my life. My partner, Anita, and I were looking for a way to pay the rent on the environment centre. She came up with the idea of setting up a volunteer-run shop as part of the premises, and I found out, to my shock and horror, I actually quite enjoyed it.

"We set up the shop at the front and the centre in the back, and that gave us a much higher profile. When we won the campaign, we still had a lease, and all the volunteers dried up. So, we bought the assets of the trust and started to run it as a business."

The smelter idea had been "voodoo economics".

"Dunedin was kind of dying in those days. People were looking for some kind of saviour to come along, and they saw this as that.

"I just thought it was a dumb idea — why would you put something like this right across from the only mainland albatross colony in the world? You were killing off the opportunity of a much better kind of future, with Dunedin as the wildlife capital of New Zealand."

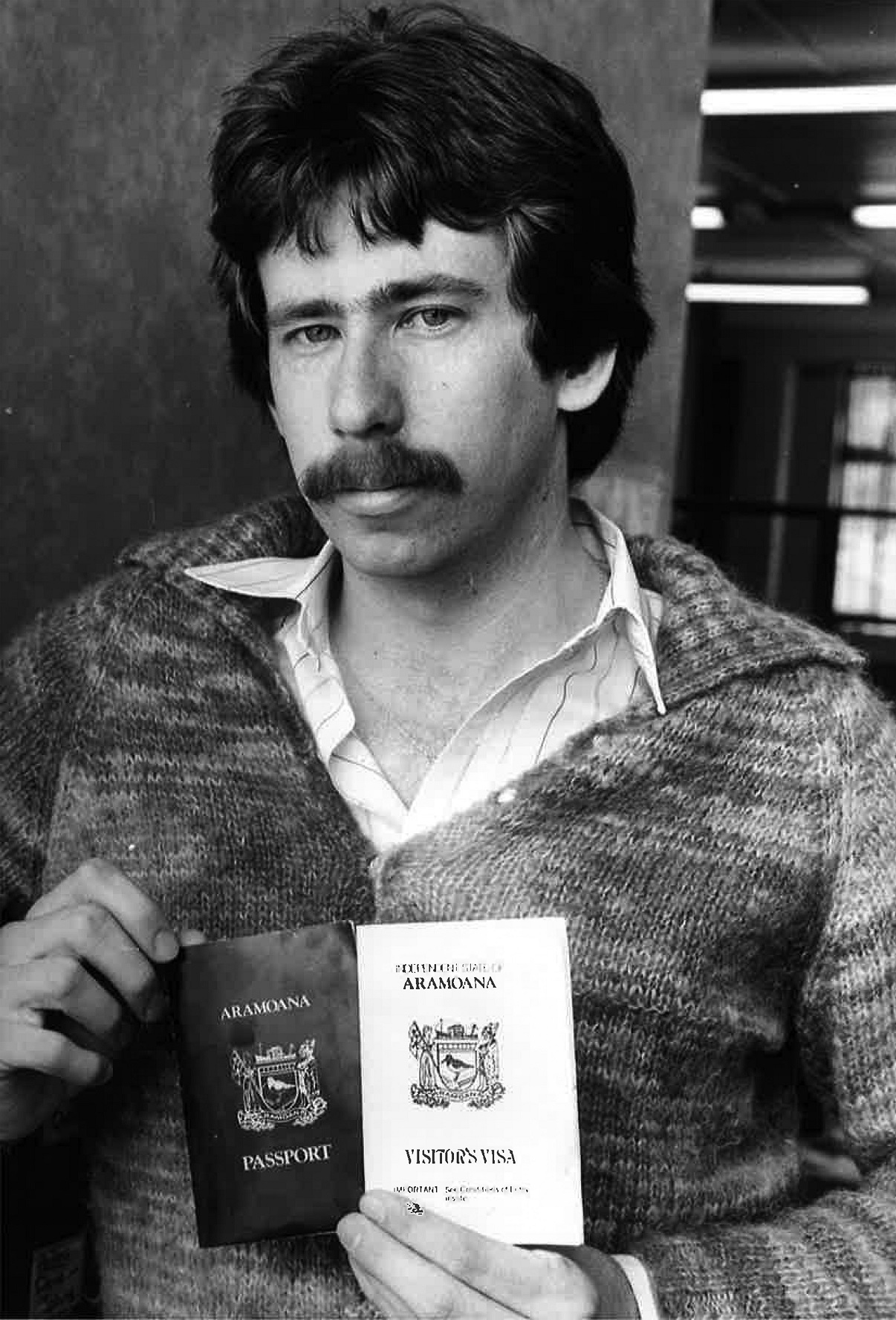

The group had to find $50,000 to take the government to court over the smelter proposal. Aramoana had already been set up as an independent state, with passport and sentry posts, and the idea was raised about 40c stamps from the "Independent State of Aramoana", featuring a Don Binney painting.

"A few people were putting them on envelopes to try to get them through in the post. And Warren Cooper, who was postmaster-general, put out a press release saying these were not legal stamps and anybody caught putting them on risked having the letters destroyed. Well, sales just took off. We couldn’t have asked for better free publicity, and we ended up raising $50,000 selling these damn stamps."

The campaign had prepared the ground for Thomson the civic leader and politician.

"My politics are left of centre. I’ve always voted Labour or Green. And financially I’ve always supported both. And I’m probably tribal in that regard.

"By that stage I’d shifted my political allegiance, if not my heart necessarily, to Labour. Probably at that stage I thought I might eventually look to go into Parliament. And I organised a rolling of — the first time that it had ever been done successfully anyway — a sitting Labour MP, Brian MacDonell.

"He was a nice guy, I’m not disparaging him, but his politics were to the right of centre, and there was somebody that we wanted to get in who we thought would be a lot better — Clive Matthewson. So, we decided we would do this. It caused all sorts of ructions."

This was early in 1984. Labour leader and soon-to-be prime minister David Lange had got wind of the plot and rang Thomson.

"Lange, who I had never met, proceeded to have a very cryptic, one-sided conversation with me. He was saying things like, ‘I cannot overstate the importance of consistency’, ‘it is a time for a steady hand on the tiller’, sort of stuff, but at no point did he directly tell me to do anything. I was to read between the lines.

"Then he despatched [later deputy prime minister Geoffrey] Palmer down to attend an electorate committee meeting. He apparently reported back that all was well and there was no evidence of any move against MacDonnell. So, when it happened, and Clive got the selection, various allegations of rule-breaking were made by supporters of MacDonnell, and the Labour Council decided to have an investigation.

"I was to come to Wellington in case they wanted to speak to me but I was instructed to stay ‘out of sight’. However, some of Clive’s supporters in the caucus wanted to see me the night before to ensure that everything was under control.

"I can’t recall exactly whose office it was — pretty sure it was Anne Hercus’. There was a knock on the door and I was instructed to hide behind it. It was Palmer who proceeded to discuss me and the meeting tomorrow. He must have thought it very odd that Hercus didn’t say ‘come in’.

"I looked across and I could see Palmer reflected in the windows and yours truly hiding behind the door. How he never noticed I don’t know."

At a party to celebrate Matthewson’s success, Thomson realised what he had done.

"Everybody was having a great time, and I felt miserable as anything. I realised that I’d ruined this guy’s life, in the blink of an eye, after he’d been in Parliament for 20 years or so. I realised I didn’t have the stomach for it and it was that night I decided this isn’t where I want to go."

At the end of the 1980s, Thomson was asked if he was interested in being on the then Otago Area Health Board. The members were then sacked by National’s health minister Simon Upton in 1993 when the boards became Crown health enterprises.

This was Thomson’s first health-sector sacking.

"That was one of the more interesting ones. We were all summoned to a meeting and kind of knew what was probably going to happen but weren’t sure.

"It was like an episode of Mission Impossible. At 7pm, a cassette was to be put in the cassette recorder," he says laughing, "at which point the recorder spewed out, ‘you’re all sacked’. Of course, it was a little more nuanced than that, but there was no other way of doing it in those days.

"In those days, the chairman had a drinks cabinet, believe it or not. Would you get away with that now? So, it was determined at some stage in the evening that nothing was to be left for an incoming administration."

Once Labour was back in power, district health boards were established in 2001. Thomson was appointed to the transitional Otago District Health Board and then became chairman and stayed on until his second sacking, by another National health minister, Tony Ryall, in February 2009.

In the meantime, health board IT head Michael Swann and Queenstown business associate Kerry Harford had been found guilty of an almost $17m fraud after issuing nearly 200 fake invoices between 2000 and 2006. Swann was sentenced in March 2009 to nine years and six months in jail, but released in July 2013.

Thomson says the Swann fraud was probably the toughest time for him personally.

"It was a massive fraud and everyone had their view. It had been set up before I was even on the board, let alone chair, and I inherited it.

"I acted on the first tip-off I received, although it took months and a new CFO to eventually uncover what he (Swann) was doing. There was no way that you could tell from board papers that a fraud was occurring. I had only met the guy twice, both in a situation where he was presenting something to the board.

"It is an interesting experience to walk into the Koru Club with everyone’s newspapers up and the front-page staring back at you saying ‘Thomson sacked’. But the upside is that the public of Dunedin and the staff generally were enormously supportive. Ryall, I think, thought sacking me would work in his political benefit, but locally it played out very badly."

Thomson had offered his resignation to Labour health minister Pete Hodgson, "who took the view that I’d taken the steps to find the person and it hadn’t started under my watch, so why would I resign?".

Once the John Key government was elected in November 2008, Thomson says new health minister Ryall was "making these remarks that the people of Dunedin were demanding accountability".

"About an hour out from the interview, there was this commotion out in the lobby, and there was a camera crew out there and a director, and the director was saying to the camera crew, ‘so as they come out of the lift, we’re gonna get them as we back into the office’. And Brian and I looked at each other and said, ‘that’s f . . . ing us they’re talking about!’.

"The whole thing was just a political stunt. Then we had this bizarre meeting where he made various statements that were factually incorrect, and we offered to correct those, but I knew the writing was on the wall.

"He rang me a couple of days later. I was walking the dog. And he said, ‘I’d like you to resign’. And I said, ‘why is that minister?’. He said, ‘well, because I don’t have confidence in you’. And I said, ‘well, why don’t you have the courage of your convictions and sack me then’.

"He got very annoyed about that and hung up. He then sacked me as chairman, but he mucked it up, he didn’t follow process. He was supposed to consult with the board, and I had the board’s full support. And I discovered how much support I had from the staff. Because I was an elected member by that stage he couldn’t sack me from the board."

Ryall, now the chief executive of early-childhood education organisation BestStart, was asked for comment but said he was "not available for this interview".

Thomson’s third sacking was less dramatic. He got called to Wellington again in 2015 by new health minister Jonathan Coleman, who had said he didn’t care what had gone on between Thomson and Ryall.

"I had three interviews and the final one was with the minister, who said, ‘well, we’re going to sack the board. We want to put a commissioner in and we want you to be one of two deputy commissioners.’ So, I had the slightly bizarre experience of being sacked at 8.59 and then reappointed at nine o’clock."

At the same time as being on the health board, Thomson was elected to the Dunedin City Council in 2010. He was re-elected three years later and became the chairman of the council’s finance committee.

The volume of work as a deputy commissioner and city councillor was the main reason he did not stand for the DCC again in 2016, despite some suggesting he might take a tilt at the mayoralty.

He finished as deputy commissioner in October 2019, when the health board returned to having elected and appointed members. However, he decided not to put his name forward.

"I felt it would be too difficult to go back to a very traditional board role after what had been about five years of an executive director role."

The story about Gary Glitter, later revealed as a paedophile, goes like this:

Thomson, who listens to everything from Beethoven to punk and says you’d be hard pressed to find a genre he doesn’t like other than rap, got the call up with a bagpiping friend to be part of Glitter’s entourage in about 1975.

"Glitter wanted bagpipers to play on one of his songs, I Love You Love Me Love. We played in front of 2000 screaming young women, mainly.

"We went back to his hotel afterwards with the band and spent most of the evening chatting to him, while his band mates disappeared at various stages with multiple women.

"He was a nice guy to chat with. I suppose the lesson is that you don’t have to be horrible to do horrible things."

Thomson likes sport, especially cricket, which he considers "the equivalent of poetry".

"It was always my great annoyance of life that so many important meetings that I had to be part of would coincide with what I would consider to be much more important cricket tests."

Thomson has been gradually shedding board and political appointments as he prepares for a kind-of retirement.

At the end of June, he stood down from the board of Dunedin City Holdings Ltd. But he remains the chairman of Central Otago Health Services, which runs Dunstan Hospital, and is a trustee of the Healthcare Otago Charitable Trust, which manages custodial funds and makes grants from them.

"It’s quite nice to be giving money away instead of saving it."

And what about the future for the "accident" that is Acquisitions?

"If you’d asked me a year ago, I’d have said I’m quite happy to do another few years. I’ve just turned 68 and I realise I don’t have the stamina that I used to have. But of course, that happens to coincide with the worst possible period in retailing for 40 years, so the notion that we might go out and sell the business right now, that would be a difficult one.

"I’d suspect we’re probably here for another couple of years."

Thomson is also deputy chairman of the Hawksbury Community Living Trust, after stepping down last year from 35 years as chair.

"The organisation I have been involved in the longest and am most proud of is the Hawksbury Trust. I set it up to care for people after Cherry Farm [Hospital] closed and then we also took over care of many people from Templeton Hospital in Christchurch.

"I was driven to create a better life for people in Cherry Farm and Templeton.

"I believe I’ve achieved that."

Inhumane places desensitised the staff

"Nothing would surprise me" in the recent Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care report, Thomson says.

He has seen first-hand some of the cruelty and horrors meted out to our most vulnerable in care homes and hospitals.

On his first day as a part-time worker at the Kimberley Centre hospital in Levin during the university holidays, he was told how best to strike patients.

"A couple of male staff came up to me. They all had these bloody great keys and all plaited like rope. And they told me how to hit one of the residents so that it wouldn’t show and warned me never to hit them after they’ve had a bath.

"Now I was too young, and I didn’t know what to do. But, you know, there were some wonderful people there, but some truly hideous people there as well. They just got desensitised, and they were inhumane places.

"As an 18, 19-year-old part-time worker, you see things that horrify you but they are normalised all the way up the chain and you don’t know what to do. This is of course how appalling treatment is able to continue. But who do you speak to? Do you have any confidence that they will believe you or even care?"

These experiences preyed on Thomson’s mind and made him determined that Cherry Farm Hospital — a mixed facility for psychiatric patients, the elderly with dementia and intellectually disabled people — should close.

"I was pleased to be involved in that closure with the area health board and also in the closure of Templeton [in Christchurch] and its replacement with something far more humane and life-affirming."

That was the catalyst for setting up the Hawkesbury Community Living Trust.

"For me, it was about there’s got to be a better way than this. And it took a lot of convincing the public. When we first started, the parents of the intellectually disabled people were almost to a person opposed to the closures.

"Within a year, we did a survey and there was only one parent who would have wanted to go back."

Cautious optimism about new hospital

From September 2015 to November 2020, Thomson was a member of the Southern Partnership Group, established to oversee the Dunedin Hospital redevelopment.

Former partnership chairman and Labour politician Pete Hodgson says Thomson has "very strong social democratic principles".

"He also has an excellent grip on how to exploit capitalism to promote those principles."

Thomson has been keenly watching the Te Whatu Ora imbroglio in recent months.

He says, despite obvious concerns, he remains cautiously optimistic the new hospital will be built largely as conceived.

"I don’t see how they can change it at this point — the costs of doing so would well outweigh any benefits. But I am less confident about that than I was a month ago. One of the things that worries me though, is that the birth process has taken so much longer than originally envisaged. If it opens in 2031, I’ll be surprised."

Despite his left-leaning politics, Thomson considers the centralisation of the health system into Health New Zealand has been taken too far in leaving no publicly elected and accountable members to represent their communities.

"There were things that absolutely needed to be centralised, but too much has been taken into the centre. It is just too big, a massive, massive organisation.

"I do worry about decisions the new commissioner [Lester Levy] might take. I don’t see how he can possibly be over the implications of those at a local level. And I’m not disparaging of him as a person at all, but I’m saying I just don’t see how you can be, it’s just too big.

"All roads lead to Wellington now and all roads lead to the CEO.

"There was a middle ground somewhere, but I think an opportunity was lost to find that."