The saying "the best-laid schemes of mice and men often go awry" is adopted from a Robert Burns poem To a Mouse.

So it is quite appropriate that it applies to this year’s Robert Burns Fellow, Mikaela Nyman.

Nyman came to Dunedin earlier this year all fired up to write her second novel, something she had been wanting to do since she published her first novel Sado (Shadow/ Shadows), a climate fiction set in Vanuatu, released just as New Zealand went into lockdown for the Covid pandemic.

"It was the worst possible launch of your first book."

However, discovering a vibrant arts community in Dunedin keen to hear and learn from her work, she has found herself distracted in the best ways.

"I feel like I’m collecting stuff and writing snippets [for the book], but I’m being quite active on the poetry scene here, which is very surprising as I wasn’t going to do any poetry this year, but it’s turning into the year of the poetry. It’s really joyful."

She has had more projects come in and been invited to share her ideas and knowledge in workshops, readings and talks around the region.

"It’s very lovely to be able to talk about your work, you move on from your work which is a pity."

It is one of the reasons Nyman grabbed the opportunity to come south from her base in Taranaki.

"It’s an amazing opportunity and certainly not one you take for granted. We don’t have a university in New Plymouth, we don’t have creative vibrant community, a critical mass of writers, so it is amazing."

The other was timing.

"I always wanted to come to Dunedin, but working hundreds of tiny different jobs as you do in the creative sector, it is pretty hard to find that time and space."

Also her high school-aged twins, who opted not to come south, are older and her daughter is studying marine biology in Dunedin.

"Especially if you are a mum, for some reason dads are OK to go off on contract, no-one bats an eyelid, but mums have a very hard time."

A residency at Massey University as a visiting artist for a few weeks in 2021 was the first time Nyman had been able to take up an opportunity to have uninterrupted time to think, write and network.

"It’s just amazing, extremely important. It’s that much harder for women to get that time off."

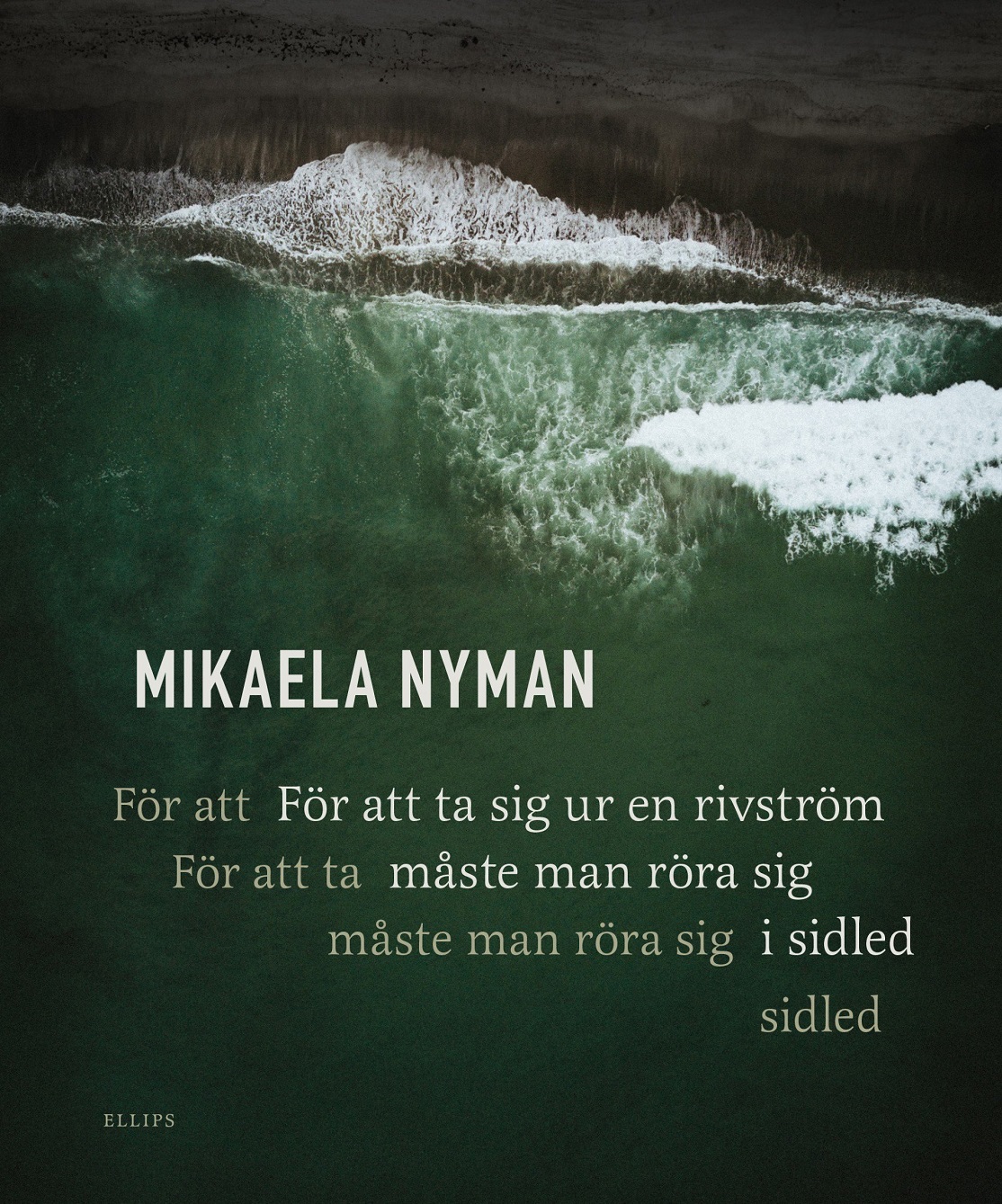

So looking forward to the fellowship and about to head south, Nyman who writes in both English and Swedish, got the news that her second poetry collection, For att ta sig ur en rivstrom maste man rora sig i sidled (To get out of a riptide you must move sideways), had been awarded a major literary prize from the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland. It had already been nominated for the Finnish Broadcasting Company YLE’s Swedish-language Literature Prize 2023 and the Nordic Council of Literature Prize 2024.

"That was so astonishing. It came as a total surprise."

"I often end up writing in the wrong language in the wrong part of the world. English is my fourth language, so it [writing in Swedish] is a way of keeping in touch with my own roots with my native Aland Islands which celebrated its centenary of autonomy in 2022 and I was very honoured to be one of the poets selected for a celebratory work for that."

Nyman is from fiercely independent islands which fought hard for their autonomy, so her works heavily feature themes of identity and belonging.

The islands where she comes from are demilitarised yet have had war planes and submarines in their air and sea space since Russia invaded Ukraine. Finland also has a long boarder with Russia.

Nyman was about to go home to visit her father and remaining family after the Covid pandemic when her father advised her not to due to concerns about an impending war.

"That was right before the war with Ukraine broke out. I’ve gone home so seldom, I’ve got five kids, uncertain job and the gig economy and then these things out of your control ... it led to my poetry collection To get out of a riptide you must move sideways."

Being from an island has also shaped Nyman’s life.

"I’m an islander from another hemisphere but everything about leaving an island for study, for jobs, or even to find partners you did not go to school with, is all the same."

Nyman did just that herself, leaving for study, work and adventure but returning home in between. It was while she was backpacking through Africa and doing peace and development studies in Zimbabwe that she met a Kiwi. They reconnected in Stockholm before travelling to Australia and then New Zealand when they had a child.

Working in Esol and also continuing her development aid work with New Zealand Foreign Affairs and Trade led to her being posted as New Zealand’s development commissioner in Vanuatu for four years.

She was in Vanuatu when tragedy struck and she lost her mother and sister within 10 months of each other.

"You are suddenly rootless. I come from a family where divorce split the family, my mother and sister were my anchor, the ones I turned to, to suddenly have that gone ..."

Nyman was also there when Tropical Cyclone Pam hit in 2015 which informed her first novel, Sado.

"The devastation was heartbreaking. Seeing how people pitch in and rebuild, the resilience of people."

While creativity has always been there for Nyman, she turned to writing, which she felt was more useful and less politically motivated, before she moved to Vanuatu, studying for her masters in creative writing from Te Herenga Waka University.

After everything that happened in Vanuatu she decided to do her PhD in creative writing alongside Pacific studies, exploring women’s expressions of creativity and under-represented public voices in Vanuatu, focusing on literary writing.

"I was wondering all the time where are all the writers in Vanuatu. All the ones I found were dead already or very senior, there was no publishing industry, no book stores but I was sure in such an amazing, creative community as Vanuatu with hundreds of languages and cultures [there must be]."

Her PhD saw her return to Vanuatu, this time facilitating writing workshops in Port Vila and continuing to collaborate with writers from Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands.

But these were not her first literary endeavours. In her 20s she was commissioned to write a biography Tankar: Hildegard Mangelus liv (1995) about a Finnish woman who established a newspaper in Kasai, in current-day Democratic Republic of Congo.

"I think, my grandad was a poet, it was his domain. It was only when my mother and sister died I had no language to express my sorrow and didn’t have anyone to share it with and I didn’t want to burden my kids."

Her first Swedish poem was written as she sat with her dying sister at her bedside. Before then she had only written a couple of poems in English.

"I really didn’t begin to write poetry until I came to New Zealand. I wrote some at her bedside just to try and survive those days."

She returned to Vanuatu where she had been asked to be acting high commissioner and buried herself in work.

"You can only push it so far and sooner or later it hits you, and poetry was the only language I could find and it was an act of rebellion to write myself back to my own language as I felt I had forgotten my own language. We were given the rights to our language and culture by the UN (or League of Nations as it was then) and we have fiercely defended that."

She has had five books out in the past five years but they have been in Swedish or about other people’s work including co-editing the first Vanuatu women’s anthology, Sista, Stanap Strong!, with Rebecca Tobo Olul-Hossen and a literary essay and a selection of Helen Heath’s poems in English original and Swedish translation.

She also has some long-standing collaborations with Vanuatuan writers that are hard to get funding for, so is also working on those this year. She is judging a Vanuatuan micro-fiction contest and trying to give back by encouraging more female Vanuatuan writers and collating and translating poetry.

"I’m also translating my latest poetry collections but I’m yet to have my first English poetry collection published."

Nyman is extremely proud the anthology changed the school curriculum in Vanuatu and at the Port Vila International School that operates on a South Australian English Curriculum for year 11.

"For the first time, the students get to read their own writers, and three generations of women writers at that."

Nyman’s new novel, a family drama in English, is fitting in and around these projects. She has also had some interest in a Swedish version of a novel she wrote 10 years ago in English.

Switching from writing in English to Swedish and back again does make life difficult, she says.

"It’s very painful, you start on the wrong foot, in the wrong language, you have a double whammy. If I write for a Nordic audience about coming to New Zealand, it’s a different thing to writing for a New Zealand audience about the people who came here. It changes everything entirely, it’s a totally new work."

While she started her writing career in English, she finds it depends on what she is writing about to what language she chooses and also what outlets are available for the work, whether it be a journal or magazine or as a book or collection.

"It’s probably easier for me to write in English."

Her poetry is often published in journals around the world which allows her to experiment and explore different types of poetry.

"I’m having a poem come out in a Tasmanian journal. It is such a romantic poem no-one would pick it as mine. It’s just ridiculous, it wouldn’t fit anywhere, but it is lovely to put out work."

Looking back over her work to date she can clearly see the themes running throughout whatever the language — memory, identity, belonging and peace.

"Sometimes, like my first poetry collection, it had to be written in Swedish not only for my sister but also for my kids to know my sister, that she meant the world to me, and it connects the two parts of my world."